ARTICLE: A Nurse on the Eastern Front

In the service of the Tsar in the summer of 1916

Plenty of people found themselves far from home at the beginning of the First World War. One of them was a woman named Florence Farmborough, who had been living in Russia since 1908. She worked firstly as a governess for a family in Kyiv, but in 1910 she took up a post in Moscow teaching English to the two daughters of a famous heart surgeon. 27 years old when the war began, instead of returning to Britain, she joined the war effort on the opposite side of Europe, working as a nurse on the Eastern Front. Her diary, which ran to a massive half a million words, was only intended for her family to read, but eventually a version found its way into print in 1974, by which time, she was more than 90 years old.

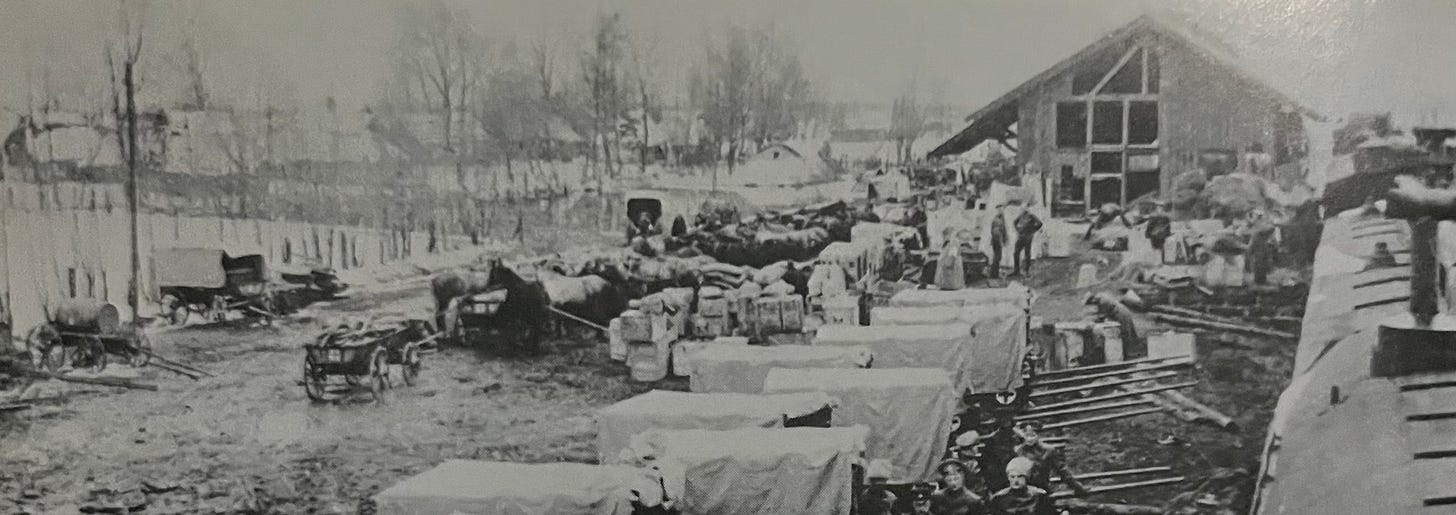

In March 1915, Florence arrived on the Galician Front, some 85 miles west of Kraków. The journey from Moscow took five days, and their location was on land captured from the Austro-Hungarians. This photo shows the scale of the operation. ‘The detrainment was a lengthy process, for the trucks were packed with ambulance vans, baggage carts, horses, hospital equipment and all the varied paraphernalia essential to a Field Surgical Unit.’ (Florence Farmborough)

I’ve chosen to dive into the diary for a few weeks at the beginning of the Brusilov Offensive, which was an epic Russian offensive that started at the beginning of June 1916 and punted the Austro-Hungarians across the battlefield on a staggering scale. By the end of the month Florence had been waiting for news of a move further forward, and it came on 24th. She would be taking up a position at a new aid post about a hundred miles southeast of Lemburg, on the southern half of the battlefront. It was clear when she arrived that the enemy had made a hasty exit…

Friday, 24th June. Barysh:

Arriving at 4.30p.m. we found the forerunners of our Letuchka installed in a partly demolished house near some devastated Austrian trenches. [They were] as ever remarkably well-constructed, smashed and shattered; wire entanglements tangled and trampled; strips of uniform-cloth were still caught up in the barbs. Craters pitted the ground on all sides; shells were piled here and there in heaps; a motor-plough stood derelict in a nearby field. There were patches of dark-stained earth where men's blood had drenched the soil; bits of torn paper, oddments of cloth, battered mess-tins, a crushed [cap] littered the ground. And there was one corner, canopied by the broken branches of decapitated trees, where stood many groups of wooden crosses. No names were inscribed - there had been no time.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Alex Churchill’s HistoryStack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.