I’m about to head to France/Belgium to research a tour for this spring with the Great War Group, and it reminded me that when I was trawling the endless rabbit holes on digital offer from the French national library, I had saved a gem that I want to write about today. The document in question is a 1923 Thomas Cook guide to visiting Paris and the battlefields. I had a stack of questions. How did they sell them? How did they work? Who did they cater for? And more importantly, how much did these offerings resemble the kind of tours that I run today? So, here goes nothing…

What were they selling and how?

This booklet is based on offering excursions, up to five days in total, from Paris. Rather than looking for a market in bringing people over from the UK specifically to tour the battlefields, this one is aimed at catching people who happen to be in Paris, or planned to visit the city. While Thomas Cook were selling them excursions there, they offered a trip to the likes of the Somme as something else to do during the course of a trip.

One thing evident from this brochure is that Thomas Cook was everywhere. Their presence on the ground was impressive. I suppose when you think about it, this was a pre-digital world where Thomas Cook would have had no website for people to gain information, where fewer people had their own cars, and where people couldn’t show up on the continent and google what they should go and see. Not to mention, this was a world where none of the war diaries were publicly available, where information about what happened where was comparatively impossible to find, and where you might have no idea where you should go, or what you should look at. To that end, Thomas Cook posted officers at major railway hubs to deal with walk-ins and to recruit tourists centring their trip on Paris. But they didn’t just post men in the city. For those who hopped a train and found themselves touching down on a battlefield, they would find a friendly rep waiting for them, with offerings of local tours there too. According to the brochure you’d find a Thomas Cook rep at Amiens station, or in the courtyard at Reims. At Verdun, there was a man in the entrance hall of the Hotel Coq Hardi. It also appears that this was open to abuse, because there is a warning too:

‘Tourists are frequently accosted by men, especially in the vicinity of our Paris offices, who falsely represent themselves to be in the employ of THOS. COOK & SON. It is recommended that all arrangements for our organised sightseeing parties and guide service be made inside our office.’

How did people travel?

Basically you purchased a spot in a comfortable automobile and a driver would fill the car, or cars, up and head out, often according to a published schedule of tours. There was also the option to purchase a private tour if you didn’t want to deal with strangers, or if your timing didn’t line up. (I’m all for this after having to travers Oman with a misogynist pig with webbed feet)

‘THOS COOK & SON have at their disposal high grade private cars of the best known makes for touring in any part of Europe, which they can furnish at short notice for journeys or tours of any kind or duration, and at the lowest prevailing rates.’

ITINERARIES can be arranged to suit individual requirements. Rates will be quoted on request with or without Hotel accommodation providing for all running expenses, garage charges, and chauffeurs board and lodging.’

You could even simply hire an interpreter, who would travel about with you ‘in plain clothes’ (Presumably to lessen your embarrassment at needing one?) ‘for any period for European Travel, visits to the Battlefields, private sightseeing and for Business purposes.’

But it’s the group tours I want to look at. Here are some of the options presented:

Where did people go?

Let’s start with this one:

THE SOMME: ALBERT, DELVILLE, BAPAUME

In One Day

There’s no set departure for this one, so I don’t know if it was less frequent? Or just more ad hoc depending on who had enquired? Passengers were instructed to locate the uniformed interpreter/‘lecturer’ on the platform at Gare du Nord; ready for the departure of the morning train to Amiens. Disembarking at the other end, the automobiles were ready and waiting, and the first stop was Villers-Bretonneux, ‘the British salient to the east of Amiens, where the Australians signally distinguished themselves.’

And here’s where it gets interesting. In 1923, the battlefields were still being cleared, and there were things to stop at that no longer exist. As the Thomas Cook customers approached the village of Chuignies they got to see an impressive war trophy.

(National Army Museum)

Thomas Cook erroneously describe this gun as a Big Bertha, but actually it was a 15in naval gun manufactured at Krupp’s. Either way, it was the shiniest of things left behind in this sector by the Germans. It had been used to bombard Amiens, 18 miles away, and was captured in August 1918 after the ‘black day’ for the German Army which kick-started the 100 Days to victory. They’d put it out of action before leaving, but nonetheless as the Australians came across it when clearing Arcy Wood they were very excited. General Monash later wrote: ‘It was a matter of great regret to me that the cost of its transportation to Australia was prohibitive.’ Instead, the gun was left in situ and designated as an Australian war memorial until the one at Villers-Bretonneux was completed in 1938.

People were expressly told not to climb on the gun, but they didn’t listen, because Tourists going to Tourist. This photo was taken in 1926. (Australian War Memorial)

In 1925, this account appears in The Scotsman describing the gun:

‘We crossed by one of the new bridges spanning this sedgy part of the river. and, turning off to Chuignes, had a look at the big gun, which the Germans placed in an excavation in a little wood to bombard Amiens and Abbeville… The big gun, with its heavy and elaborate machinery, is rusting where it was left, except that a twelve-foot length from the end of the barrel has been cut off and erected in Sydney as a war memorial.’

The Nazis, being massive spoilsports, destroyed what was left of the gun during the Second World War.

In the meantime, the Thomas Cook touring party then crossed the Somme, reaching Albert for lunch.They’d have found the town prior to restoration:

‘The visitor will see the ruins of the Cathedral, from the tower of which, the famous virgin, after leaning over perilously for many months, through having been struck by a shell at the beginning of the war, fell shortly before the termination of hostilities, thus fulfilling one of the "prophecies" of the war.’

Then it was on to Fricourt, Mametz and Montauban, also still in ruins, as it was explained to them that these were all objectives for the British in 1916. They drove past a lot without stopping, which if you’d have come all this way must have been annoying, not least because there must have been stuff everywhere:

‘Bernafay Wood, with Trônes Wood, in the distance, are seen in passing on the right… also Delville Wood, a veritable death trap under the German guns… Nothing now remains of the wood except a few dead stumps of trees. Flers, or the spot where the village once stood, famous as being the place where tanks were first used, is passed before stopping at Bapaume.’

Once again, they would have found ruins where the town once stood, before they then bounced around several early memorials:

‘The monuments erected to the Tank Corps; 2nd Australian Division, to 13 different Battalions of the Kings Royal Rifles, and the 1st. and 2nd Australian Division, are seen before reaching Pozieres and Thiepval.’

An early shot of the memorial to the 1st Australian Division at Pozières. (Australian War Memorial)

Thiepval was given the billing it deserves, but this was a long while before the memorial was built, and so presumably they were there for the view. Likewise, the Anglo-French cemetery didn’t yet exist. Those casualties would be brought in from as far away as Loos in the early 1930s. Nearby Connaught Cemetery was already there, as it dates from 1916, as was Mill Road, but this brings me to an interesting point. This brochure mentions only two cemeteries in its entirety. Considering how much of a central part they are to modern battlefield tours, I wonder if they did stop, but just didn’t talk about it because they didn’t want to seem morbid in the brochure? Or was this actively not a focus on these early Thomas Cook tours? Either way, this sound like it was an incredibly long day. The drive back to Amiens went back via Albert and Querrieu, which took the distance covered to nearly 90 miles before customers were deposited back at the station for the first class journey back to Paris.

This brochure was far from Brit-centric. Here’s another tour on offer:

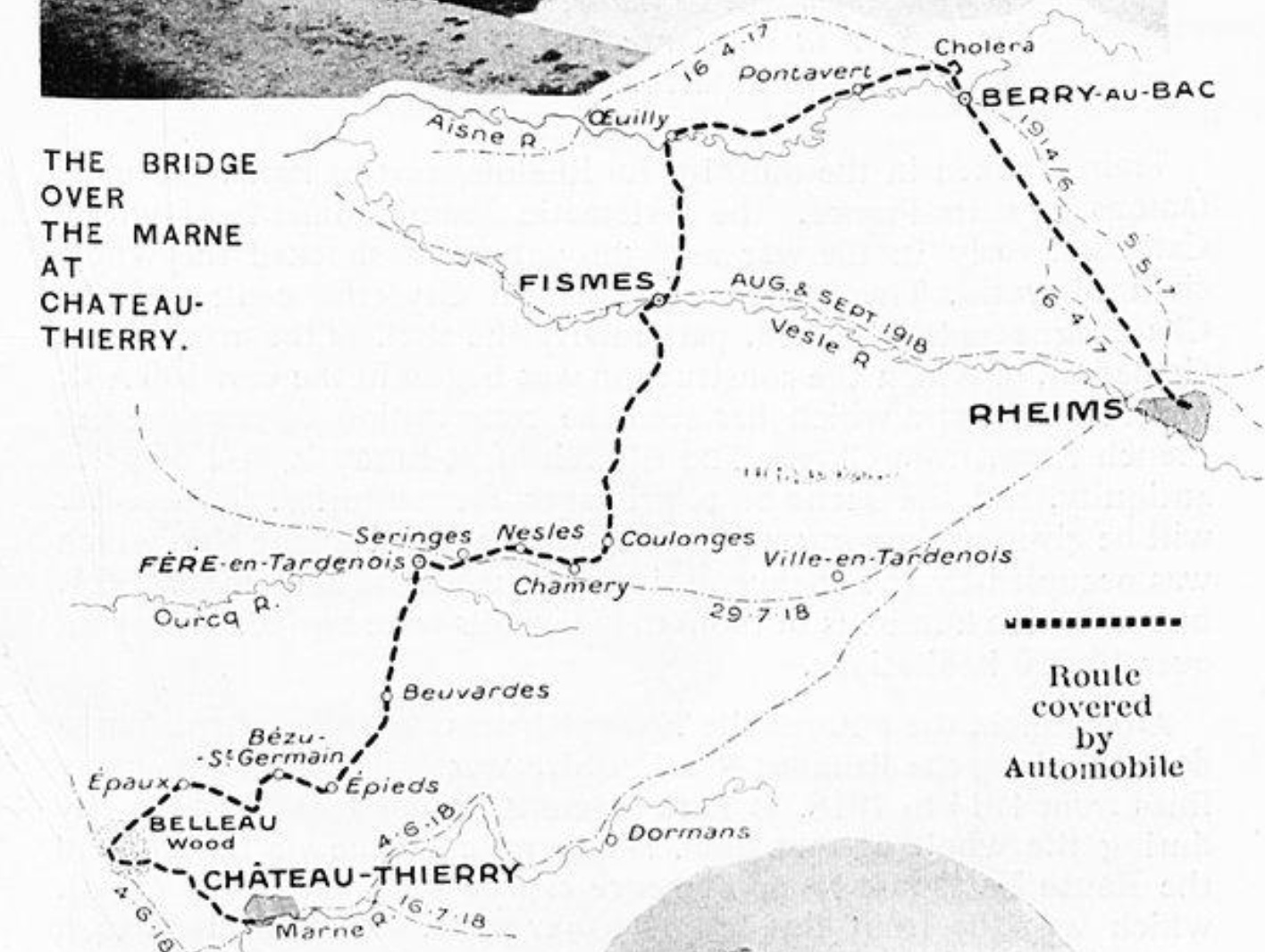

CHATEAU-THIERRY, BELLEAU WOOD, FISMES & RHEIMS

In One Day

This time passengers had to report to Gare de l’Est half an hour before the morning train to Reims. On arrival, they would do Thomas Cook’s standard morning tour of the city before lunch, and then, the motors arrived. The first stop was the ruined factory on the road to Berry-au-Bac, which obviously is no more.

‘Here the complete destruction and the ruins of the sugar factory show evidence of some of the most ferocious artillery duels in the war, while Hill 108, now a gaping mine crater, gives an idea of the terrible effects of this mode of warfare.’

(https://cartorum.fr)

This is one of the tours where we get mention of a cemetery, specifically what is now Oise-Aisne American Cemetery, but beyond that, we actually get a stop to see a specific American buried nearby.

20-year-old Quentin Roosevelt was the youngest son of President ‘Teddy’ Roosevelt, who had left office in 1909. Serving as a pilot in 1918, he was shot down in the area in July. Here’s an account available all over the internet by Lieutenant Edward Buford, who was also reported missing that day but had managed to get his plane down at a French aerodrome:

September 5, 1918

Father dear,

You asked me if I knew Quentin Roosevelt. Yes, I knew him very well indeed, and had been associated with him ever since I came to France and he was one of the finest and most courageous boys I ever knew. I was in the fight when he was shot down and saw the whole thing.

Four of us were out on an early patrol and we had just crossed the lines looking for Boche observation machines, when we ran into seven Fokker… planes. They had the altitude and the advantage of the sun on us. It was very cloudy and there was a strong wind blowing us farther across the lines all the time. The leader of our formation turned and tried to get back out, but they attacked before we reached the lines, and in a few seconds had completely broken up our formation and the fight developed into a general free-for-all. I tried to keep an eye on all our fellows but we were hopelessly separated and out-numbered nearly two to one. About a half a mile away I saw one of our planes with three Boche on him, and he seemed to be having a pretty hard time with them, so I shook the two I was manoeuvring with and tried to get over to him, but before I could reach him, his machine turned over on its back and plunged down out of control. I realized it was too late to be of any assistance and as none of our machines were in sight, I made for a bank of clouds to try to gain altitude on the Huns, and when I came back out, they had reformed, but there were only six of them, so I believe we must have gotten one.

I waited around about ten minutes to see if I could pickup any of our fellows, but they had disappeared, so I came on home, dodging from cloud to cloud for fear of running into another Boche formation. Of course, at the time of the fight I did not know who the pilot was I had seen go down, but as Quentin did not come back, it must have been him. His loss was one of the severest blows we have ever had in the Squadron, but he certainly died fighting, for any one of us could have gotten away as soon as the scrap started with the clouds as they were that morning. I have tried several times to write to Col. Roosevelt but it is practically impossible for me to write a letter of condolence, but if I am lucky enough to get back to the States, I expect to go to see him.

(Wikipedia)

In subsequent years, Roosevelt’s grave became a popular pilgrimage stop for people on this part of the Western Front. The Thomas Cook tour makes sure to include it, before driving on to Fere-en-Tardenois. If you were to visit the spot now, you wouldn’t find him. In 1944, Quentin’s brother Ted died of a heart attack and when he was laid to rest at Normandy American Cemetery, Quentin was subsequently reinterred to be with him.

I’m starting to doubt this tour now, because it then has a stop to see Belleau Wood, still a massively important spot for the US Marine Corps, before then taking in the sites of Chateau-Thierry before putting people on the train back to Paris. For me, this is at least two days of content. It’s also all over the place in terms of the conduct of the war, which raises an interesting point. If these early tourists were getting to see things that are no longer there for us to take in, they were missing out in other ways thanks to the wealth of historiography and available material we can draw on to plan tours of the battlefields now. There’s no rigorous going over of battlefields to drill into what happened on this spot and why. By nature of the content crammed in, these tours can barely have stopped at a location before they were off again.

These exclusions don’t strike me as actually having been designed for people with a loved one to visit, or with a personal attachment to a particular place that they’d want to discover. I feel like if you did have one, you’d be left feeling very shortchanged as you flew past on the way to something else. Still. Thomas Cook were certainly working hard to take advantage of the very beginnings of the battlefield tourism industry, and I’m sure with a name that well-established, they found plenty of takers.

Alex Churchill’s HistoryStack is a reader-supported publication. Generous subscribers pay for the time and expense it takes to research and write content for the cost of one fancy coffee a month. If you join them, you’ll be receiving articles for as little as 52p each..

You can download the original brochure from Thomas Cook via Gallica here.

We visited Ypres and the Somme in 2015 with several of the original Michelin guides in hand, it really brought home the devastation.

Thanks for this so interesting article...👏👏👏👏👏