Tell me if this sounds familiar: A towering public figure who loves the sound of his own voice, who starts off by positioning himself as the face of change, something special, the man who’s going to make your nation the bestest nation of all. He’s loud, and he’s shouty, and he clearly thinks he’s a big deal. People are excited. But actually, it turns out that life and circumstances conspired to put him in a position that though he clearly thinks he was born for it, greatly outstrips his capabilities. Time goes on, and it transpires that though he’s great at the talking and the slogans and the whipping people up, he’s not so great at the doing. People begin to see through the shouting. He’s definitely not the brightest guy in the room, and he’s always flitting from one cause to another, without actually nailing down what he promises. Eventually, he just becomes exhausting. The longer he’s around, the more he becomes a bit of an embarrassment, and various government officials, politicians, family members, the press, all begin taking him less seriously. They can’t ditch him, because of the position he wields, but they back away and try and distance themselves from the rhetoric. Half the time, he talks gibberish. At times, you can picture the sensible adults in the room with their heads in their hands, very much wishing he’d just shut up.

I’ve just described the public life of Kaiser Wilhelm II from his ascension to the German throne in 1888 to the onset of the First World War. Bearing all the above in mind, I was plodding through some French books the other day, and I came across one I definitely wanted to write an article about. In 1918, a Madame Marie Méring decide to collate the Kaiser’s public speeches from throughout the First World War and publish them in one place. This is going to be good, I thought. Merci, Marie…

Making Germany Great (Again)

The Kaiser is a fascinating study. A lot of Wilhelm’s rhetoric from 1888 onwards was about reaching back into history. Germany was only unified in 1871, and so he had to, to try and generate the kind of symbolism, pomp and pageantry he wanted to inject into a monarchy that was actually new in this incarnation. Image wise, his rhetoric was all about bringing back medieval vibes, and tying himself to the perceived grandeur and the chivalry of the Middle Ages. Don’t forget he’s Queen Victoria’s oldest grandson. He’s seen this kind of precedent and imagery in action since he was a boy, and he wanted it for himself too.

That doesn’t have to be a bad thing. The Kaiser was not an evil man. There’s nothing wrong with wanting your country and your people to prosper. The tragedy of the First World War is that there is no insidious force like the Nazis that needs dispensing with. There’s no good guy and a bad guy. Almost without exception, every nation’s hands were as filthy as those of their neighbour.

There was no road map for any monarch at the beginning of the war. It would take George V more than a year to build and streamline his role. Constitution wise, Wilhelm wielded much more power. His placed him at the head of the army, but in reality, nobody was expecting this of him. King Albert of the Belgians was the only crowned head of state to actually lead his troops in battle in the First World War. He was considerably younger, and not carrying a physical disability like the Kaiser (he only had one complete arm) and even then, it was touch and go as to whether he actually would take on this responsibility. If you’ve got your thinking cap on as a monarch, this is ringing all sorts of alarm bells. If you are in charge of your troops, and they fail, you are directly responsible for that failure. Tsar Nicholas II was a glaring example of why you should probably try and dodge this bullet as a monarch. He didn’t, and it contributed heavily to the loss of his throne, and then his life.

What you get from Wilhelm at the onset of war is safe; exactly what you’d expect, a figurehead for the war effort to rally and unite a nation for the coming struggle. Here’s some of a speech that he read to the Reichstag on 4th August 1914:

‘With an honesty that nothing could disturb, my Government has even, in the midst of the circumstances that provoked it, pursued the development of all moral, intellectual and economic forces as its supreme goal…

For our legitimate defence, with a clear conscience and pure hands, we take up the sword. To the peoples, to the races of the German Empire goes my appeal to defend with all their strength, in fraternal union with our allies, the results of our peaceful work. Following the example of our brothers, resolute and faithful, serious and chivalrous, humble before God and full of warlike ardor before the enemy, we have confidence in the eternal Omnipotence which will be willing to give strength to our defense and bring the fight to a successful conclusion.’

The key to this measured, sensible rhetoric is that he read it. The Kaiser did not write it himself. He knew, however, to get a crowd going, and at the end he riffed some material of his own:

‘You have read, Gentlemen, what I said to my people on the balcony of the palace. I repeat: I no longer know parties, I only know Germans. (Impetuous bravos) To show me that you are firmly resolved without distinction of party, without distinction of class or religion, to follow me everywhere and always, even in distress and until death, I invite the party leaders to come and shake my hand as proof of their oath.’

The problem with the Kaiser, is that by 1914 he’d already demonstrated that he was volatile in terms of public speaking. This riffing was a common theme, and the results had at times been embarrassing because the message he’s supposed to be conveying starts getting muddled, or disappears altogether. This proclamation from two days after the Reichstag speech sounds much more like his own voice:

‘To the German people,

Since the foundation of the Empire, for forty-three years, my most ardent efforts and those of my predecessors have been to preserve peace in the world and to work peacefully for our powerful development.

But our adversaries envy us the success of our work. Coming from the East and the West and from the other side of the sea, we have to endure, with the consciousness of our responsibility and our strength, an avowed and latent hostility. And now they want to humiliate us.

We are required to watch with folded arms as our enemies prepare for a sneak attack. We are not allowed to remain resolutely faithful to our ally, who defends her position as a great power and whose humiliation would be the loss of our power and our honour.

The enemy attacks us in the midst of peace. Let us rush to arms! Any delay, any temporisation, would be a betrayal of the fatherland. "To be or not to be," such is the question that is posed to the Empire, which our fathers have reconstituted. It is a question of being or not to be for German power and Germanism. We will resist to the last breath as long as we have a man and a horse. We will sustain the struggle even against a world of enemies.

Germany has never been defeated when she was united.

Forward, with God who will be with us as he was with our ancestors.’

Not the best, but not a disaster either. The opening months of the war are characterised for Wilhelm by his lurking about behind the emerging Western Front waiting to make triumphant entries into various French cities. His point of reference is the Franco-Prussian War, which was over very quickly, and I suppose he’s looking at the Schlieffen Plan, which aimed to knock France out of the war quickly. The problem is that when the war doesn’t end, and the Schlieffen Plan is wrecked once and for all on the Marne at the beginning of September, he ends up looking a bit silly.

In classic Wilhelm fashion, he turned his attentions elsewhere, namely the Eastern Front, and from here, in 1915 he remained solid if a little fast and loose with certain facts. Here is part of an address that he gave in Russian Poland in February:

‘The advantage we have over our enemies is that they have no rallying cry. They know not what they are fighting for; they know not for whom they are being killed. They carry upon their shoulders the heavy bag of a bad conscience, for they have attacked a peace-loving people, while we march against the enemy with the battle-pack of a clear conscience. Nevertheless, to achieve success it is necessary that every man do his duty, and I expect and require of you that every man shall be in full health and strength until victory is ours. The enemy must be completely defeated and I will dictate the terms of peace with the points of my soldiers' bayonets.’

Then this comes from an address he gave in August to Saxon troops in what is now Ukraine:

‘Behind you were raised hands to supplicate the Almighty, and the clouds were torn apart and the God of hosts looked down upon you. I am here to bring you in front of the smoking citadel my gratitude and the gratitude of the entire fatherland. You have carved your exploits in the annals of history with mighty hammer blows. You were able to do this because you trusted in God. You thought of your loved ones back home. They stood behind you, their hands raised in supplication, the Almighty, and the clouds were torn apart and the God of hosts looked down upon you. In front the people who fight, in the rear the people who pray: this is how it must be! You were able to win because you knew: We are within our rights! Only in this way can battles be won!’

He’s all but preaching here, and the religious justification is something that he would continually return to throughout the war. There’s broadly the same message in all of this. Through no fault of her own Germany has been forced into an existential fight and with unity and perseverance, she will fight for the right to enjoy peace. It’s muddled and a bit waffly, but there’s a point being made. This is where I call grace. This is the high point of the Kaiser’s rhetoric during the First World War.

Wilhelm on one of his many visits to meet with troops during the war. (Library of Congress)

Fake News

Wilhelm had been dabbling in spin since 1915. This is part of an interview he gave in February:

‘When they say of me abroad that I intend to found a world empire, it is the greatest absurdity that has ever been said about me. In the conscience and the ardour for work of the German lies the conquering force which will open the world to him.’

By any stretch of the imagination, the notion that Wilhelm has no interest in forcibly claiming an empire is laughable. From ill-judged telegrams, to gunboat diplomacy, he had been personally involved in several moves towards trying to impact imperial affairs, or add to German interests prior to 1914 and none of them were rooted in conscience and hard work. They were rooted in catching up with established empires like the British and the French, in claiming Germany’s rightful share.

Spin is one thing, but by 1916 he was just making things up. Let’s fact check his ‘orders of the day’ to the army and navy on the second anniversary of the outbreak of war, in July of that year:

‘The second year of the world war has passed. Like the first, it has been a year of glory for Germany.’

The first year of the war was not a year of glory for Germany. At the very least, this is selective history. From August 1914 - August 1915, Germany could claim to have the upper hand on her sectors on the Eastern Front overall. On the Western Front, the best you can say of the German war effort is that Germany had managed not to lose the war. The strategic plan to kick France out of the war effort early and turn the whole of Germany’s strength on Russia in the east had failed. Additionally, attempts to break through to the Channel coast had been wrecked in Belgium. Further attempts to force the issue on the Ypres Salient in 1915 had also failed. Further afield, Germany’s imperial territories had shrunk dramatically. They were simply too isolated to withstand any sustained attack by powers with bigger empires and more far-flung infrastructure. The fact that Germany’s enemies also had total control of the seas meant that the German Navy had achieved little beyond some commerce raiding.

Where the Kaiser’s claim completely falls apart is carrying this claim through to August 1915 - August 1916.

The Germans had attempted to smash France to pieces at Verdun and months later, had not succeeded. They never would. Additionally, the German armies in the west were now having to withstand (costly) progress being made by the allies on the Somme. Added to this, German forces were now having to be siphoned off and sent east to bolster their Austrian allies in the face of the terrifying impact of the Brusilov Offensive.

‘On all fronts you have dealt the enemy heavy blows.’

I supposed that’s fair.

‘Whether the adversary has given way before the power of your attack, or whether, made more powerful by foreign aid collected by force in all corners of the world, he has tried to wrest from you the prize of your victories, you have constantly shown yourselves superior to him.’

I’m not even sure what he’s trying to say here, but that last line, again, nope. Not by any stretch of the imagination. Where the war was not categorised by complete deadlock, (which in itself implies that the two forces are evenly matched) anywhere that the German army was attempting to get the better of the enemy, they were failing to succeed. And here is the big one:

‘…Also where the domination imposed by England was uncontested, on the free waves of the sea, you have fought victoriously against an overwhelming force and superior.’

This is the most ridiculous example of fake news propagated by Wilhelm during the First World War. He is claiming that the German Navy won the Battle of Jutland. He did this frequently. Here is more from the end of the year:

'The greatest naval battle of this war, the victory of the Skagerrak, the bold undertakings of our submarines guarantee our fleet eternal glory and admiration.’

Britain suffered heavier losses, but the battle ended with the Germans fleeing the scene for the safety of their ports and they never came out in force again. If either side was claiming anything more than a score draw, they were outright spreading falsehoods. That line about the submarines is an outright lie, too.

‘the bold undertakings of our submarines guarantee our fleet eternal glory and admiration’.

At the point when he said this, the Germans had had to pull back on torpedoing merchant ships with impunity because of just how badly their submarines had made them look within the international community; the worst case being the Lusitania. I’d venture to guess that at literally no point did German submarines contribute to any feelings of admiration outside of Germany and countries allied with her.

They’re evil.

By 1917, we’re descending into the twilight zone. We’ve gone beyond some silly statements and some doctoring of the facts. I think in part, it has to do with the lack of defined role for Wilhelm in this war. He seems to bump about, not really sure of what he’s supposed to be doing. In terms of political or military influence, he has receded further and further into the background. The issues with his attention span, I believe, are a contributing factor. It’s been a characteristic of his reign, that when he doesn’t get the results he wants, quickly, and the hard work of achieving them becomes a factor, he moves onto the next thing.

In terms of public speaking, the Kaiser’s original rhetoric cannot be employed anymore. Clearly victory has not been claimed, and casting Germany in a righteous role in the face of godless enemies does not make sense when you’ve employed unrestricted submarine warfare, unleashed gas on the battlefield and displayed abundant evidence that your actions are every bit as grubby and unforgivable as the enemy.

As the war went on, Wilhelm’s rhetoric became convoluted and baffling. He doesn’t know what to say given that victory has not been forthcoming. This one is a good example of a path he often trod, focuses on the despicable nature of Germany’s enemies. They’re evil:

‘Our enemies are reaching out with a greedy hand toward German territories. They will never obtain them. They are constantly pushing new peoples to war against us. This does not frighten us. We know our strength and are determined to use it. They want to see us weak and helpless at their feet, but they will not throw us down… They slander the German name throughout the world, but they cannot destroy the glory of German exploits.’

Claiming that God is on Germany’s side is a common refrain. This is part of a speech from May 1917:

‘The English… he fights, obstinate and stubborn as he is, only to increase his power at our expense. We remain resolute in loyalty, work and the accomplishment of duty. On which side is the right, there is no doubt about it. And that is why this fight has become a holy fight.’

Here’s another from the end of the year:

‘The year 1917 with its great battles proved that the German people have in the God of Armies, Up There, an ally in whom they can have complete confidence. They can count on him completely…’

They’re cheating

We actually get this as far back as December 1915:

‘They have long since buried the hope of defeating us in fair combat. Today they dare not trust anything but the weight of their masses, in the annihilation of all our people by famine, in the effects of a campaign of slander as criminal as it is perfidious that they are waging throughout the world. Their plans will not succeed. They will sink miserably before the spirit and the will that unshakeably unite the army and the country, before the spirit of duty towards the fatherland to be fulfilled until the last breath, before the will to conquer. This is how we enter this new year. Onward with God for the protection of the fatherland, for the greatness of Germany!’

I’m the smartest

By 1918, we’ve descended further, and we’re now into the realms of gibberish. There are convoluted attempts from the Kaiser, despite having placed himself in a place of utmost importance with his rhetoric so far, to distance himself from this lack of victory. This odd one is from June 1918, when German attempts to win the war have just about run out of steam once and for all:

‘The German people did not see clearly when the war broke out what meaning it would have; I knew it very precisely... I knew very precisely what it was about, because England's participation meant the world war, whether wanted or not.’

This is from the same time. The Kaiser claims to have ‘known’ all along what this war was about, and he smells a conspiracy of sorts:

‘The first explosion of enthusiasm could not deceive me or bring about any change in my aims and my hopes… It was not a strategic campaign, it was a struggle between two world views. Either the Prussian-German, Germanic conception of the world: right, freedom, honour and morality must remain in honour, or the Anglo-Saxon conception which means: to indulge in the idolatry of money. The peoples of the earth work as slaves for the Anglo-Saxon master race which holds them under the yoke. The two conceptions struggle against each other.’

By the time he gave this next speech, at the Krupps works in Essen in September 1918, Germany was facing defeat:

‘I know very well that more than one of you, during this long war, must have often asked yourselves this question: How could this happen, why did this have to happen to us, since we have had forty years of peace? I believe that this is a question that deserves an answer. It is a question that must also be answered for the future, for our children and grandchildren.

'I have thought about it for a long time, too, and I have come to this conclusion. We all know it from our youth, from our current situation and our observations: in this world good fights against evil, this is how Heaven has decided; the yes and the no, the no of the doubter against the yes of the finder, I would like to say; the no of the pessimist against the yes of the optimist, the no of the unbeliever against the yes of the Hero of the faith, the yes of Heaven against the no of Hell.’

He’s also descended well into the realms of the conspiracy theory. Here is an example:

‘You have read what has just happened in Moscow: the great conspiracy against the present Government. The democratic people of the English, governed by a Parliament, have tried to overthrow the ultra-democratic government that the Russian people have tried to establish, because this government, taking into consideration the interests of the fatherland, has obtained for the people the peace for which it cries, while the Anglo-Saxon does not yet want peace. This is how things appear. This is proof that one feels one's inferiority when one resorts to such criminal means.’

For some context, he’s talking about Allied intervention in the Russian civil war. The ultra-democratic Russian leadership he’s referring to? I shit you not, the Bolsheviks. He also declines to mention any of the German interventions throughout the Tsar’s fracturing empire at the time.

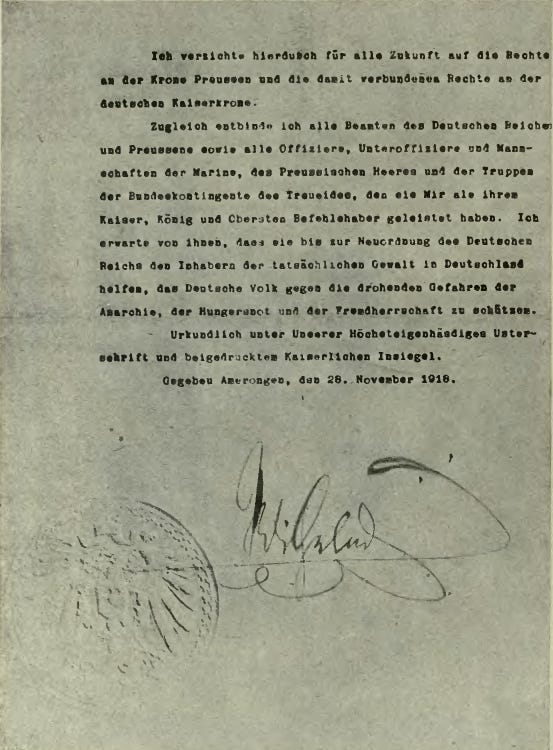

The book ends before we get to the big one. Wilhelm did not even get to announce his own abdication, which should tell you everything you need to know about how things ended for him. By the end of the war, he had no public voice. Germany was in the midst of a revolution, and the abdication was taken done on his behalf by Chancellor Max von Baden on 9th November, 1918. By the time he got his say it was almost December. Personally, the move was seismic; ending half a millennia of Hohenzollern rule. For most Germans, they had other concerns by then. The official abdication statement, written, not spoken, is void of all bombast, all sense of entitlement:

‘I herewith renounce for all time claims to the throne of Prussia and to the German imperial throne connected to it. At the same time I release all officials of the German Empire and of Prussia, as well as all officers, non-commissioned officers and men of the Navy and the Prussian Army, as well as the troops of the federated states of Germany, from the oath of fidelity which they swore to me as their Emperor, King and Supreme Commander. I expect that until the re-establishment of order in the German Empire, they shall render assistance to the holders of power in Germany in protecting the German people from the threatening dangers of anarchy, famine and foreign rule.

Certified under our own hand and with the imperial seal attached.

Amerongen, 28 November 1918. Wilhelm.’

At the very last, did Wilhelm finally get that it wasn’t about him anymore? Probably not. I doubt he wrote that himself.

A copy of the abdication statement (Wikipedia)

Not Learning to Let Go

Even if he did, when revolution and unrest waned and a new Germany emerged, he was embittered. David Lloyd George wanted him sailed up the Thames in the style of Anne Boleyn to be tried as a war criminal and potentially executed. Of all people, Churchill was the voice of reason. That and George V loudly protesting to anyone who would listen. In the end, we have the Queen of the Netherlands to thank for the fact that we were spared that circus. She refused to hand him over.

Wilhelm did not die until the Second World War was already in progress. In his later years, from exile in the Netherlands, he spouted bile about all manner of parties that he blamed for his position; mostly Jews, or Britain. He dreamed of a comeback, of a return to power in some form. He flirted with Hitler when he thought he might facilitate this, and at other times he despised him when it was clear that the Führer would never give him what he wanted.

Wilhelm as he looked when he officially abdicated.

The former Kaiser was 82 when he died of a pulmonary embolism. It was June 1941, and Hitler was about to invade the Soviet Union. Never one to miss a propaganda opportunity, Hitler embraced the prospect of a state funeral, himself in a place of prominent mourning, the symbolism of some sort of inheritance passing from the dead Kaiser to himself in front of the world. Wilhelm got one over on him in the end. He left orders that his body was not to be returned to Germany unless the monarchy had been restored first. Hitler had to stand down, and to this day Wilhelm lies buried on foreign soil.

The book I’ve referred to throughout is Les Discours de Guillaume II Pendant La Grande Guerre, edited by Marie Méring. It was published by Editions Bossard, in Paris, in 1918.

Reading the first paragraphs this description could have been - Boris, Don … etc,etc … turns out as time unwinds their real talent is the brass neck to bullshizzle their way through even though they must know they can’t actually do the thing!

Those first few lines had me reliving our current situation in the USA. I’m pretty sure that I have political PTSD since mid 2015!

Thank you for look back!