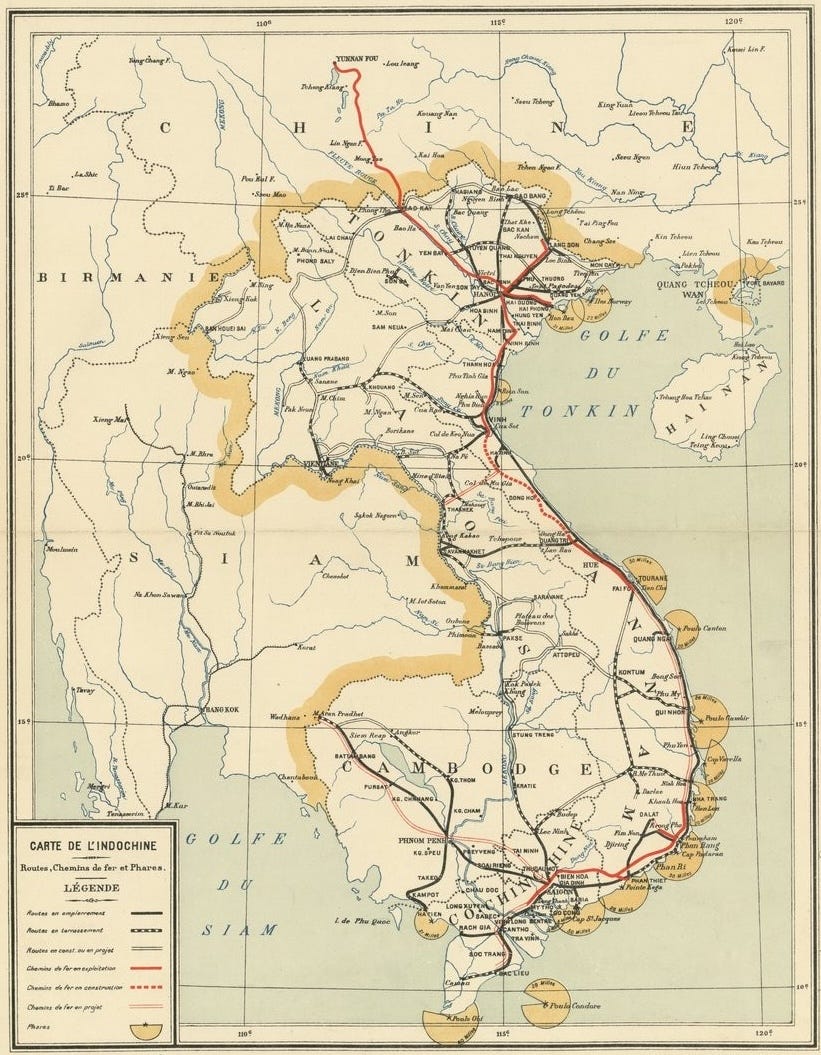

The French had been in Southeast Asia since the 1860s, and by the Second World War, their influence held sway over pretty much what is known as Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and the Chinese province of Zhangiang today. After the French capitulation of June 1940, the Vichy Government ended up taking the reins under Japanese occupation. This uneasy scenario prevailed until the liberation of France at the beginning of 1945. By then, Japan, knowing that her eventual defeat was inevitable, intended to go down swinging. The government in Tokyo decided to stage a coup against French colonial occupation of Indochina beginning on 9th March. Why? Regardless of how terrible their predicament was, this move was all part of their ambition to have a ‘Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.’ One that didn’t involve European powers. What followed was a forgotten reign of terror that would impact ordinary Frenchmen and women until Japan finally threw in the towel in August, and have consequences far beyond…

(Wikipedia)

There were two phases to the atrocities carried out by the Japanese in French Indochina in 1945. The first was a frenzied, immediate and violent series of incidents that happened along with the initial coup, and to a large extent these widespread massacres were carried out against French troops. The most savage fighting occurred in Tonkin. At some point I will go back and do a military article on how this played out, but probably as a result of significant Japanese losses and a refusal to stand down on the part of French troops, this was ground zero for the most inhumane acts carried out by the incoming Japanese troops.

Second Lieutenant Louis Chomette and his men had done everything in their power to resist at Fort Brière de L’Isle, despite aerial bombardments and the use of poisonous gas on the part of the Japanese. In the aftermath, somewhere between 60 and 80 prisoners, including the wounded, were rounded up and tied in two rows, they backs to the wall of the fort. Almost all of them were white were white, because the Japanese had separated them from the their indigenous comrades. One exception was Gunner N'Guyen, who refused to be separated. "I have always lived with the French, I want to stay with them," was his explanation. Now, along with the other prisoners N’Guyen faced two machine guns. One of the Frenchmen, 26-year-old Lieutenant Duronsoy, had been wounded twice, but now he begged that the men be spared and only the officers shot. His request fell on deaf ears. At 4:30pm an NCO by the name of Fujiki pulled a man out of the lineup and decapitated him with a sabre. Knowing that they had little time left, the remaining prisoners began to sing the Marseillaise. They got two verses in before the machine-guns opened fire and men moved in to finish them off with bayonets. Only three men survived and were subsequently able to crawl out of the ravine into which the victims had been tossed. ‘We had barely fallen,’ explained Chomette:

when, with their usual cries, the Japanese rushed at us with fixed bayonets and began a fencing exercise in which they hardly feared the response. I was wounded almost immediately in the hip and arm. For about an hour and a half, they attacked us, pricking one after the other at first, then randomly, following the death rattles or movements. I was wounded again in the chest. I was eager to receive the final blow. [...] Finally, calm, I heard the riflemen talking near us, they cut my bonds and tied me by the feet. I was pulled face down for about 50 meters. A rifleman took off my shoes and stockings, a last hiding place for the money, then a good push and there I was rolling down the slope of the hill. I landed among the rocks of the scree a little roughly, but without any further injury. Others follow the same path. I am in a very bad position, head down, but impossible to move, we can still hear talking not far away. Finally, night falls.’

Louis Chomette (www.fnvc.com)

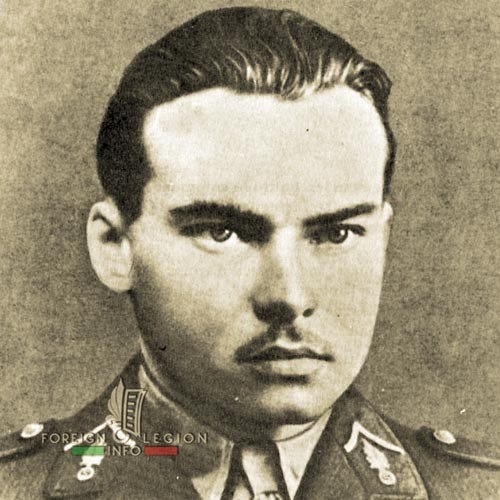

Lieutenant Michel Duronsoy, who pleaded for the lives of his men. (www.foreignlegion.info)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Alex Churchill’s HistoryStack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.