The moral of this story is never walk past an Oxfam without checking out the books because you never know what you might find…

In 1851 the population of London was booming. Nearing two and a half million, as people continued to migrate in from the countryside in search of work, it would more than double in the course of the next thirty years. Plenty of those people were living in a miserable state of abject poverty, and this was the era of the “Great Stink”, but it was also a period of impressive regeneration and development. Battersea, Hackney, Earls Court were all still outlying villages, but railway lines were beginning to sprawl throughout the metropolis, new bridges were connecting up settlements on either side of the Thames for the first time. Familiar landmarks like Regent Street were being put up in a fashion that would be recognisable today. It was not only at home that Britain prospered, and it was into this new, fast-moving, exciting world that Great Exhibition was put up, to celebrate modernity, style and progress… Thus facilitating me shoehorning dinosaurs into my substack…

The Concept

The idea for the exhibition came out of the Society of Arts, and was based on some small scale displays put up in the 1840s. There had been one or two solely industrial expos like this in France, and they had been replicated provincially in Britain. There had also been a Free Trade Bazaar at Covent Garden in 1845, but nothing had been done on this scale before, incorporating industrial progress with tasteful (at the time) cultural displays, or drawing inspiration from across the entire planet.

Prince Albert was one of the major figures behind the plan to bring this lofty idea to fruition, and he was already fully committed by the summer of 1849. Queen Victoria’s consort does not deserve all the credit, though. Henry Cole was a relentless public servant and supporter of the arts who was significant too. The fundraising was epic, and needed to be; including a massive loan underwritten by a lot of disgustingly rich influencers that amounted to more than £41 million pounds in today’s money. Supported by huge names such as Brunel and the Duke of Wellington, the committee now needed to find somewhere to put it.

The Building

The venue was always supposed to be a temporary one, and Albert had focussed on a vacant spot in Hyde Park, between Kensington Drive and Rotten Row. Conveniently, permission came down to the Crown, so this was no barrier. Joseph Paxton was a self-made man who had been made head gardener at Chatsworth House by the Duke of Devonshire at just 23. His niche was fancy glass houses/conservatories and soon the Duke had him working diligently to improve a stack of massive houses he owned throughout the country. By 1851, he was the most famous gardener in the world.

The Crystal Palace (now the name of a nearby football team who have the misfortune to call Croydon home and play in arguably the worst ground in the Premier League) was based on the Lily House Paxton had constructed at Chatsworth. This was literally built to pander to the whims of a six inch plant seedling from British Guiana, because what else are you going to do with obscene amounts of money when buying up social media outlets and promoting fascism isn’t an option. Paxton’s new structure, however, obliterated the scale of this. In all, 1060 iron columns were used, bolted together to support 2,224 girders, thirty miles of guttering, and 202 miles of sash bar. 600,000 cubic feet of timber was also needed.

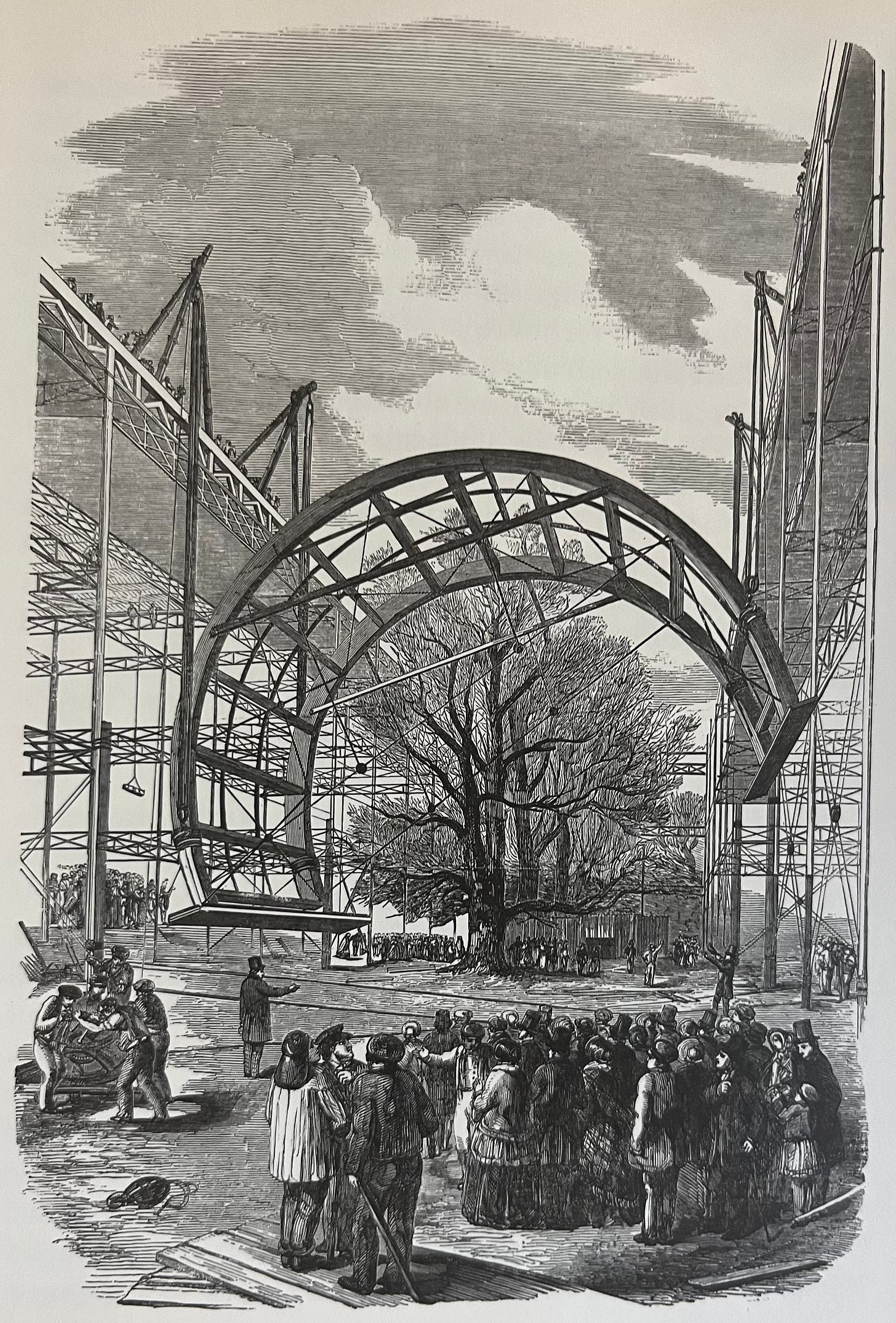

This image from the Illustrated London News shows one of sixteen arch sections being lifted into place. They were made of laminated timber and they were all hoisted into place inside a week.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Alex Churchill’s HistoryStack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.