FREE ARTICLE: The Heroine of Gallipoli

The SS River Clyde

Today marks the anniversary of the disastrous landings at Gallipoli in 1915. If you can have a favourite thing about an unmitigated sh*tshow of a military campaign that resulted in the callous deaths of thousands based on a plan that makes Kanye West look like a genius, then mine is the River Clyde, the troop transport with a difference.

If you don’t know this story, hang on tight, because the Royal Navy are about to steal a boat back from the French, ram it into Turkey and attempt to take over…

Why?

For those that don’t know, at the beginning of 1915, the First World War was not going well for anyone. Deadlock had emerged on the two main fronts, east and west.

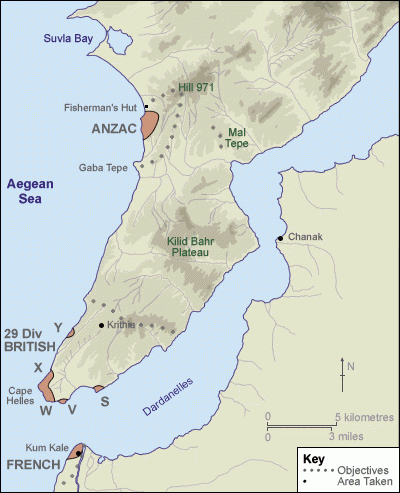

Some genius in London (the civilian head of the Admiralty at the time, some bloke called Churchill) decided he had a great idea. Using the Royal Navy he was advocating busting through the Dardanelles, which led into the Sea of Mamora, and then grabbing Constantinople from the Turks, who had entered the war on Germany’s side in November 1914 after doing a very bad job of appearing neutral. (Map: Australian War Memorial)

The naval plan to conquer Turkey from the water was bad. It failed to properly take into account all the forts and the mines and all the Turks that would want to stop them. Even when the Allies got their backsides handed to them in a naval scrap that Turkey still celebrates today, they doubled down. By the end of March 1915, they had resolved to send a land force if ships were not going to work. There weren’t that many troops available, (in fact, arguably there were none to spare at all for this idiocy) but they were going to spread them out in order to invade more beaches at once. This is also a bad plan. Then they were going to seize the high ground. They would do all of this in a couple of days. There are a variety of bad reasons why they surmised this, even though they didn’t have proper maps. These included the wonderfully imperial sentiment that the Turks were not white soldiers and therefore wouldn’t put up much of a fight. Face palm.

For context, there were even more stupid ideas on the table that involved trying to win the war somewhere other than in France, but the fact that they chose this one as if it might work means that Churchill took the flack this time. In fact, by the time the Allies ran away with their tail between their legs, he’d lost his job and thought his political career was over.

What?

The River Clyde was nothing to look at. In fact, she was pretty hideous when her new crew found her at Mudros less than two weeks before the landings at the Dardanelles were supposed to take place. Captain Edward Unwin had been called out of retirement to participate in the war. He had a particular job in mind for this 4,000 ton collier, which he had convinced the Royal Navy to charter back from the French against their will. Unwin had her stores thrown off and got to work.

How?

The captain’s plan was this:

Just after the initial wave had landed at Cape Helles, Unwin would crash River Clyde into V Beach with part of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force on board. Her deck would be covered in machine guns, and when they hit landfall, 2,000 men would burst forth and conquer.

Obviously they weren’t going to get out a gangplank for everybody to wander ashore in full view of the Ottoman Army, and so multiple doorways were cut in the outside of the ship and ‘galleries’ tied with ropes to the sides of the hull, sloping downwards to where it was anticipated that small boats, which had been towed along for the adventure, would be waiting to ferry them the last few metres to dry land.

The inside of the ship was downright disgusting when Midshipman George Drewry arrived to lead a party of Greek volunteers in cleaning it. Having sailed all over the world, he claimed that she was the dirtiest ship he’d ever seen. The last thing the French had used her for was bringing across mules from Algiers, and she was in exactly the same state that those mules had left her in. I like to think that was the French response to us forcibly taking the ship back from them. 1-0 France.

By the time she as ready, the ship looked ridiculous. Clearly something bonkers was afoot, and now Unwin set out to find enough crew to make the trip. They were going to have to volunteer, as in consent, because orders or not this mission was lunacy. When he approached the existing crew, whose last job had been as dull as babysitting the mules, a spokesman said something on the lines of ‘not on your life.’ So instead, Unwin went back to his old ship, where he found far more enthusiasm. He recruited six seamen and six more ratings for the engine room. A sprinkling of petty officers were added, an engineer, a surgeon, a carpenter and last of all, George Drewry, who would have followed Unwin anywhere.

Getting Ready to Leave

Troops began arriving at Mudros and trudging aboard the River Clyde. They had come from Alexandria, weighed down with ammunition, waterproofs, firewood, three days of iron rations and a water bottle that they were not allowed to touch unless somebody gave them permission. They included a collection of Irishmen, Worcesters, Hampshires and detachments of specialists like signallers and a company of Royal Engineers. Anticipation was building. Sub-Lieutenant the Honourable Arthur Coke watched them all being crammed aboard. ‘We run ashore on this ship at 5.30 tomorrow morning,’ he wrote home:

‘I only pray everything will go satisfactorily and no shell will strike this ship as… it would mean a terrible loss. They are coming on board now off the transport, and are being packed like sardines in the holds.’

For these men, the chances of any sleep were pretty non existent. By the time the men put their heavy kit down, there was no room to sit down. The air quickly became oppressive. It was going to be a long night. That’s the one thing they don’t tell you. These big life or death battles in history? Most of the time the men that fought them were exhausted by the time they reached the battlefield. And hungry. As the River Clyde, the plan had been to provide the men aboard her with a hot dinner. Not a chance in these conditions. Everyone, officers and men alike had to put up with bully beef and biscuits; a semi-warm cup of tea if they were lucky. ‘The lower [holds] must be a pretty fair reproduction of the Black Hole of Calcutta,’ wrote one naval officer, ‘and we have been doing our best to keep them going by making enormous cauldrons of coffee in the galley and handing it round.’

At least one survivor was adamant that they had no idea where they were going, and that at most they had briefly rehearsed going up and down ladders into little boats. There were no large-scale practice runs for this ambitious, amphibious landing that would not be matched in scope until Guadalcanal.

On course for V Beach: a grainy shot of the River Clyde closing in on Cape Helles just after dawn on 25th April. (With thanks to Stephen Chambers)

25th April 1915

As the sky turned from black to grey and the sun began to come up, the bombardment stunned the men preparing to land. ‘It was a wonderful sight,’ wrote one of the officers due to lead the Hampshires ashore.

‘Destroyers hurtled across our bows, rushing to the Straits to cover the [battleships]… The flashes and thunder of the ships' guns, the rush of the big shells over our heads towards the land, and their terrific explosion on impact, together with the mild excitement caused by the enemy's shells pitching near us, and the [concern] as to what would happen when the ship was struck… and finally whether we should come under a tremendous fire on landing, everything combined to make an ineffaceable impression on one's mind.’

Sub-Lieutenant Coke, far left, with Petty Officer David Fyffe, second left, and a party of machine-gunners beside one gun emplacements on the River Clyde shortly before the landing (with thanks to Stephen Chambers).

(Australian War Memorial)

Gallipoli today is a stunning landscape to look at. On this morning it was cloaked by a cloud of black smoke tinged yellow, with gun flashes going off within. On the bridge, Unwin was already running late. In fact, he was slowing down. He couldn’t see the boats they were towing to carry men the last bit of the way to shore. There was no wind to blow away the smoke from the guns, but time for procrastination was fast running out. The River Clyde was already pointed at the beach, the French were already on the way to their landing place across the water and he couldn’t cut across them. Ships on either side of them were blasting away to subdue the enemy ashore, he couldn’t cut across them either. They passed close enough to a navy ship for Unwin to call out and ask if they knew whether the boats were in place. ‘The reply he got was: “Don't know, but go on in.”’

Unwin decided to go for it:

‘I jammed the helm hard-a-port and just managed to clear the stern of the [Albion] but saw that I could not clear two destroyers lying on her starboard side with a sweep out between them [a wire for dragging for mines, submarines presumably] so I did the only possible thing [and] went between them knowing that they had plenty of time to slack down the wire and let us run over it.’

Disaster averted, they were half a mile out, and half an hour late. All Unwin cared about now was spotting the best place to beach his ship:

‘It was very difficult to locate the beach owing to the smoke and dust, but I had luckily taken a trip up the week before, and had taken a transit of a sort of gravestone on the beach in line with a conspicuous tree on the hill. I got these in line and made for them.’

Impact

The scratch team in the engine room had done their job, she was making good speed. The River Clyde was operating at the limit of her humble powers. The hull shook, oily black smoke poured from her lone funnel. The machine-gunners on the deck had a perfect view of land rushing towards them,‘all wondering what would happen when we struck the beach.’

The ships now stopped firing on Cape Helles, it was about to be covered in British troops. ‘An uncanny silence reigned.’ 200 yards out, a shout went down into the holds of the River Clyde to get the men to lie down and brace for impact. A klaxon sounded, a last warning, and then, nothing.

Johnny Turk.’ Before the campaign, the Allies were guilty of grossly underestimating their value as soldiers and the determination they would show to fend off invaders. (With thanks to Stephen Chambers)

Behind the beach, befuddled, the Ottoman troops had not slept properly for two days. British ships had been torturing their sleep patterns by firing at the coast for several nights. So far that morning, they had withstood a monstrous bombardment from the water. Now, as the naval guns fell quiet so as not to obliterate their own troops, the Ottoman defenders crawled from their shelters and battered trenches and steeled themselves at the sight of the invaders.

The transports, the naval vessels and the lines of boats that were being towed in, they could get their heads around. The River Clyde, not so much. She was pointed right at the beach. This was no port, there was no dock. And it didn’t appear to be slowing down. Eventually, the intention became apparent. Why would they run her aground?

On the ship, a voice came down into the hold. 'All right, she's aground.’

The moment the ship beached was completely underwhelming. ‘It was hardly credible. There had not been the slightest vestige of a tremor through her, and she was perfectly upright ... some 40 yards or so from the beach.’ In the holds the men were stunned. At most they had felt a slight grinding sound, or noticed a shiver run through the hull. Some had felt nothing more than the ship gently slow to a halt.

On the bridge, Captain Unwin was annoyed with himself. The River Clyde was in a dangerous spot. 'As I feared,' he wrote, 'it was a little too far to the eastward. We were on the extreme edge of the reef. Still, we weren't far off.' What she was, however, was under the guns of the enemy; a giant, sitting duck stuff with men who now had to get ashore.

Attempting to Land

This was because Ottoman officer Major Mahmut Sabri was not an idiot. Amphibious landings are hard. The advantage is always with the men that have already set up to defend the coastline, even if his force was not overly large, so he was in no hurry. He had issued orders that his men were to wait to lay concentrated fire down on the approaching enemy until they were far bigger targets.

His ploy was devastating to the Dublins when they made landfall in their open boats. On the River Clyde, George Davidson was brave enough to stick his head out of one of the makeshift holes in her side to see what was happening:

‘It was an extraordinary sight to watch our men go off, boat after boat, push off for a few yards, spring from the seats to dash into the water which was now less than waist deep. It was just at this point that the enemy fire was concentrated. Those who got into the water, rifle in hand and heavy pack on back, generally made a dive forward, riddled through and through, if there was still life in them, to drown in a few seconds. Many were being hit before they had time to spring from the boats, their hands were thrown in the air, or else they heaved helplessly over, stone dead ... Along the water’s edge there was now a mass of dead men [and] on the sand a mixture of dead and wounded.’

Boat after boat full of men attempting to land was decimated by Ottoman fire. Private Martin watched all but two of his fellow passengers die in his boat:

‘It was sad to hear our poor chums moaning, and to see others dead in the boat. It was a terrible sight to see the poor boys dead in the water; others on the beach roaring for help. But we could do nothing for them... I do not know how I escaped. Those who were lying wounded on the shore, in the evening the tide came in and they were all drowned, and I was left by myself on the beach. I had to remain in the water for about three hours, as they would fire on me as soon as they saw me make a move. I thought my life was up every minute.’

Major Mahmut Sabri's men were merciless in trying to push the invaders back:

‘In a vain attempt to save their lives, the enemy threw themselves from the boats into the sea… In spite of the terrific enemy artillery and machine gun fire directed at our trenches, our fire was very effective and was knocking the enemy into the sea. The shore… became full of enemy corpses, like a shoal of fish.’

The Doomed Campaign

It had always been the plan to leave the River Clyde where she had beached. She served the until the end. Unwin had purposely taken an engineer qualified to set up water filtration on board, so that troops ashore would have continuous fresh drinking water. The ship became a dressing station, a store, a landing stage, it’s not exaggerating to say that she became a rusting but immoveable symbol of the campaign. She was the thing that everyone who went to the tip of the peninsula remembered.

For the entire duration of the campaign, the River Clyde dominated the scene at Cape Helles.

When the time for the Allies to leave Gallipoli, the role of the River Clyde was as pivotal as on their arrival. The plans involved trying to get as many men out of the way before the Ottomans noticed and a bloodbath ensued. The bulk of the men being evacuated walked along a pier, disappeared into the stripped hull of the ship and out of sight of the enemy boarded trawlers on the other side to depart.

The evacuation of the Gallipoli peninsula was the biggest success of the campaign, which was depressing. For many of the men leaving, the last thing they recorded seeing of this miserable experience was the darkened hulk of the River Clyde looming above them. Her last job of subterfuge done, the River Clyde was to be abandoned. One Admiral wanted to destroy her in an epic fit of arson by dousing her in cans of petrol. Perhaps she could be blown up when the last of the troops were safely away? As it was she was left alone. As the least men sailed away from this doomed campaign, she was dimly illuminated by the fires burning ashore of everything from military equipment to a random bowler hat that nobody wanted the enemy to have.

The spot where the ship lay in 1915 today.

In 1919, a salvage company refloated the River Clyde. There was an idea to moor her on the Thames as a monument but in a post-war economy, nobody was going to spend money on that. Having been fixed up at Malta she was sold to Spaniards. Seized in 1937, she served the Nationalist cause during the Spanish Civil War out of Santander. She rescued three British airmen during the Second World War, and was almost saved from destruction. Once again, the British Government wouldn’t put up the money. She was finally scrapped in 1966.

I’d make a case for the suggestion that she was the most badass, resilient member of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. But I’m biased towards the boaty stuff.

If you would like to read the full story of the River Clyde, you should definitely get hold of the book ‘The Wooden Horse of Gallipoli’ by Stephen Snelling. It’s excellent, and packed with quotes and first hand observations. With thanks to Stephen Chambers for use of just a few gems from his outstanding collection of photos of the campaign.

What an extraordinary story and ship. All new to me. It’s a pity in 1966 that someone didn’t think to save her.

Superb. You tell it like it was. Really enjoying your substack material.