FREE ARTICLE: Canned Crab & Suicides Pt.I

The declining fortunes of the Japanese in 1944.

This is a written, truncated version of the talk I just gave at We Have Ways Fest 4. To mark the 80th anniversary of the end of Japanese ambition in the Pacific, I talked about the critical loss of Saipan, and the change in tactics that was then adopted at Peleliu, making it one of the most hideous experiences in this theatre for the US Marine Corps…

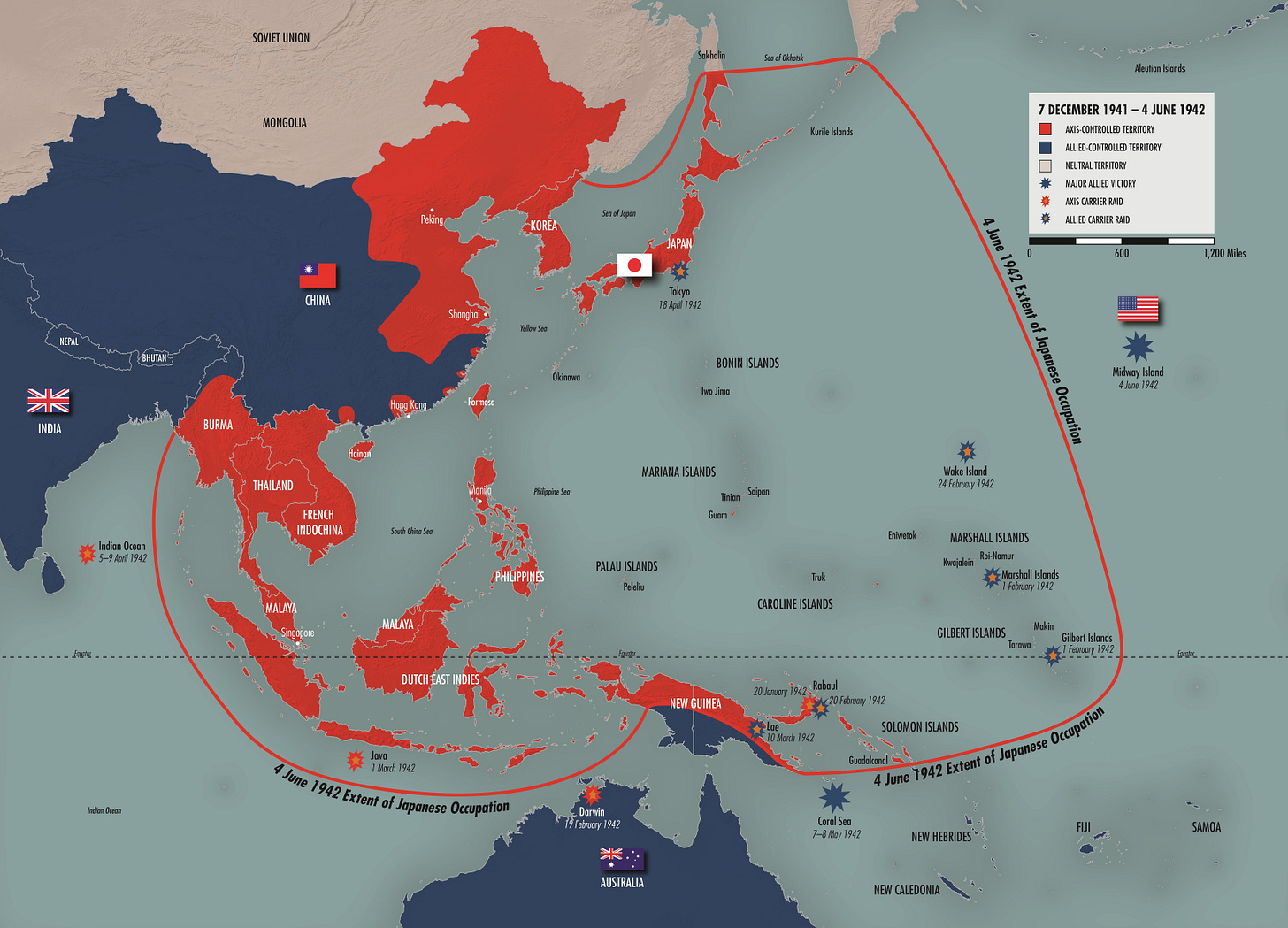

I started off by explaining how overextended the Japanese were by 1944.

(National WWII Museum, New Orleans)

Pearl Harbour was not an isolated attack. It was part of a massive drive out across the Pacific to add to Japan’s Empire. It was a huge commitment in manpower. Bear in mind Japan had a population of about 75,000,000 during WW2. The following numbers are upper limits, and men would have been shuffled about. Also, they include some of the collaborate and puppet state troops.

Allow for about 500,000 men in the army air services. In 1943, I have a figure of roughly 750,000 in the navy. In terms of land forces, 320,000 served men in Burma, along with some 4 million in China. That doesn’t include Manchuria. A total for that has eluded me but I did find one of about 750,000 for the Kwantung Army, which was the one that stomped out of Korea and blew a hole in a railway igniting WW2 in 1937. Then there are nearly 8 million men who served on two fronts in the Pacific, one either side of the Equator.

All of this was an enormous endeavour in resources too. It’s part of the reason that Japan launched itself on such a ridiculous scale in the first place. They were looking to nail down supplies of things like oil and rubber. During the talk I used one example, and that was the production of the Mitsubishi Zero in 1944:

The factory in Nagoya had doubled its workforce, and yet in 1943 only managed 50% of its target output. In 1944, it was supposed to turn out 40,000 aircraft, and it was clear early on that this was a pipe dream. There was a lack of materials for construction, bad logistics, deficient numbers of skilled workers, and an inability to utilise mass production techniques. At the end of 1943, finished aeroplanes were being dragged out of the factory and some 25 miles for delivery by oxen. Yep. The Japanese war effort was partly dependent on pack animals that they couldn’t feed.

All of their offensive plans for 1944 lay away from the Pacific. Here they intended to contract in on themselves, and when that idea went to sh*t because the plans were captured, they were intent on waiting for the Americans to try and capture the Marianas and luring them out into a decisive naval battle.

Marines Advance at Saipan (Library of Congress)

The Americans very much planned to be offensive in this theatre. The Gilberts, including Tarawa, and the Marshall Islands had been seized, And now, after plenty of the usual in-fighting and inter service dick-waving (TM) it was time to leap on those Marianas as the Allies attempted to bounce across the Pacific towards Japan itself.

There are a number of reasons why it made sense to take this chain of islands. They would make a good base for the Pacific Submarine Fleet. They were also on the route south from Japan on the way to important imperial possessions. Most importantly for me, though, from the airfield on Saipan, the first of the islands they were going for, a B-29 bomber could reach Japan’s home islands.

On 29th February 1944, Op Forager was signed off. It was a broad plan for the rest of the year. First off it required the seizure of the Marianas. The second part, which I also talked about, was another jump westward, to the Palaus.

The invasion of the Marianas was launched nine days after Overlord in Normandy, on 15th June 1944. If not for the other D-Day, it would have been remembered for its epic scale. More than 300,000 were sent, and more than 600 ships. Task Force 58 alone had 15 aircraft carriers.

I talked this year and last about the unique challenges of fighting a campaign in the central Pacific. There are a number of them that made this amphibious landing more complicated that what was happening on the Normandy coast.

Distance is one. From the Marshall Islands to the Marianas is the equivalent of London to Istanbul. That journey is pretty much entirely across empty ocean. If it took a matter of hours to cross the Channel to France, the journey here would be a minimum of five days for troops wedged into transports. There are also no resources you can claim and utilise. The Americans had to take absolutely everything with them. There were a ton of supplies for each man they intended to put ashore. Those aircraft carriers were each carrying eight million gallons of aviation fuel. One witness was awestruck by the sight of this armada:

The wakes from all those ships were perfectly symmetrical with each other… I looked down on this power and wondered what kind of fools the Japanese were. They had made the greatest miscalculation of all time, and boy, were they going to pay a price.

The northern part of this huge force was heading for Saipan. Three days later, to the south, more troops were supposed to land at Guam, but this was to prove wildly optimistic. At WHW in 2023 I talked about Tarawa, which was a tiny speck on the map, an atoll with elevation no higher than a sand dune. Saipan was massively different. This island was twelve miles long. Past the beaches, it was made up of rugged terrain covered in thick jungle, with inconveniently wide gorges and mountainous high ground as a spine. There were sugar cane fields that made advancing awkward, and thanks to 30,000 inhabitants, there were also towns to factor in. It had been estimated that there were 17,000 Japanese defending the island.

That estimate was about to turn out to be woefully inadequate.

Lessons had been learned from places like Tarawa. The Americans had learned to test their beaches properly before they attempted a landing. They’d also learned to pay proper attention to tides. One key thing, too, was the stark reminder of how important it was to absolutely and effectively flatten your target before you attempted to land.

To that end, the bombardment of Saipan began on 13th June, with guns targeting the areas directly behind the landing beaches on a four mile front. The day before the assault was launched, underwater demolition teams went in too. They sound like absolute lunatics. Under heavy artillery fire, they were dropped on the reef to blast away coral and clear paths for the landing craft, and it worked. The first waves got in on the beaches without much opposition. In eight minutes, the marines had at least a tentative grip on every beach.

By the time the fourth and fifth waves came in, however, the Japanese fire had increased. It also happened to be extremely precise. They shattered the reef in such a coordinated effort that the watching Americans thought that a line of mines had been simultaneously detonated. One officer crawling up a beach saw two men obliterated by a mortar round:

There was an explosion and these two guys just evaporated. We couldn’t see any of them. They were disintegrated, just mixed in with sand and vegetation and scattered all over the place.

Nonetheless, by the end of the day, the marines had penetrate up to 1,500 yards inland. 20,000 pairs of boots were on the ground, along with seven battalions of artillery.

In command of the amphibious force, General Holland Smith of the US Marine Corps had by now realised that the estimate for the number of Japanese on the island was too low. In fact, rather than 17,000 men the garrison comprised more like 30,000. The planned landings at Guam were called off for the time being, and all available reserves were requested for Saipan. Those reserves arrived in the shape of the 27th Infantry Division, and these army men were directed towards the airfield on the southern part of the island.

Opposite, the Japanese developed a routine of delivering their counter attacks at night. When they began on 16th June, they were not subtle about it. The US Navy watched them form up and then pummelled them with their guns. The resulting scrap was an all out melee at close quarters. Behind, the beach continued to fill up with the wounded. The scene was horrific:

All along the beach men were dying wounds. I want you to know what it was like. Mortar shells dropping in on heads and ripping bodies. Faces blown apart by lead and coral. It wasn’t a pretty sight, and I will never forget the death and hell along the beach. It rained all the night and the mud was ankle deep.

On the third day, in a combined effort the 4th Marine Division and the 27th Infantry Division powered across the island and reached the opposite coast, severing the link between Japanese defenders in the south from their comrades. The airfield was secured and at this end of Saipan, it was now a case of mopping up little pockets of resistance. The main job now was to turn north and roll up the rest. And here’s where the invasion got problematic, because the Americans had now run up against the mountainous spine of the island. Thick vegetation allowed the Japanese to employ guerrilla tactics, and progress ground to a halt.

A large-scale attempt to break the deadlock was launched on 23rd June. On either flank, two lots of marines blasted their way past the Japanese defenders. The army, however, were not so lucky. To be fair to them, they were faced with the more difficult terrain, but starting an hour late, the impetus soon drained out of their attack. Part of this might have been down to different doctrines in action; marines charging forward and worrying about mopping up later, while the army did things in a more deliberate and methodical (i.e. slower) manner. This isn’t necessarily wrong, but on a cramped battlefield, defended by a scrappy, insurgent style enemy, it wasn’t effective. Cue more inter service dick-waving and the dismissal of the 27th’s commanding officer, who was sent back to Pearl Harbour. But what did this prolonged campaign mean to the men doing the fighting?

It was 120 degrees and we stayed all day in the hot sun and were slowly going crazy. I couldn’t open my mouth at all, my tongue was swollen five times its normal size, my throat burned to a crisp, and blood coming out of my nose and mouth.

What I find really interesting, too, is the total lack of comprehension about where these men are in the Pacific. They have no clue.

To each of us, the most important place in the world was his foxhole. Most marines were as ignorant of Pacific geography as their families at home.

A Japanese Soldier Surrenders at Saipan (Library of Congress)

It took another week, give or take, to break the deadlock, and it was messy; lots of screaming banzai charges and flamethrowers. The Japanese determination to fight on for as long as possible in the face of certain defeat and probable death was a constant refrain. That’s indisputable, but I also think there’s a tendency in the west to almost see Japanese troops as almost inhuman fanatics. This is an account from a 26 year old soldier defending Saipan:

The area I was in was pitted like the craters of the moon. We just clung to the earth in our shallow trenches. We were half buried. Soil filled my mouth many times, blinded me. The fumes and flying dirt almost choked you, the next moment I might get it!

He was also surrounded by the remains of his comrades:

Corpses burned black, hanging from the branches of trees, tumbled into the ground. Corpses crawling with maggots.

In command, on 6th July General Saito informed Tokyo that the island was lost. He issued one last order. Parts of it read:

Heaven has not given us an opportunity. We now have no materials with which to fight our comrades have fallen one after another. I will advance with those who remain to deliver still another blow to the American devils. I will leave my bones on Saipan…

He didn’t. He had a last meal of canned crab with his officers and then committed ritual suicide. 3,000 odd men did, however, make one last stand. Some of them had makeshift weapons such as bayonets tied to wooden poles. Some of them were wounded and just hobbled along at the back unarmed. One American witness wrote:

It was the most spectacular banzai charge of the war.

Afterwards he remembered ‘wading through the slime and details of entrails, gore, splintered bones, mangles flesh and brains.’

Saipan fell shortly afterwards. Out of a garrison of some 27,000, less than 750 were taken prisoner. The Americans had suffered, too. 3,000 were killed, and 10,000 more wounded. The Marianas were in Allied hands, and it was a decisive win.

To find out what happened when the Americans moved on to Peleliu, which I also talked about last weekend, come back later in the week. It was to be an even more deadly experience, that claimed thousands more lives on both sides and changed the face of the fighting in the Pacific for the rest of the Second World War.

On average my posts take three-four days to write. If you like what you see, for the cost of one takeaway coffee a month) please consider helping to fund the time it takes to produce them by becoming a subscriber.

The sources for this one are many, but most of the quotes come from Ian Toll’s Pacific trilogy, or from Bitter Peleliu, by Joseph Wheelan.

The longer WHWF4 was awesome Alex but this is a great taster. Keep up the great work you guys at Great War Group and History Hack are also doing

It was an excellent talk - there’s not a lot to laugh about in this part of the war but you managed to entertain a packed, riveted crowd for an hour on the subject. Looking forward to the next instalment.