FEATURE: The First Battle of Arras, 1914

(Or the adventures of a little man in a beret)

The Race to the Sea isn’t quite accurate. In the words of General Foch, who was about to assume command of France’s northern armies on the emerging Western Front in autumn 1914: ‘The phrase sounds nice, but it does not give a true picture of the operations. The race was towards the enemy.’ What he meant, is that both sides were actually racing to get around the open flank of their foe and around the back, where they could pull off a decisive manoeuvre by causing chaos in the rear and, hopefully, finish their prey off by encircling them. As in turn the Allies and the Germans put a new force on the northernmost end of their line to block this happening, so the fighting shifted upwards, until they reached the Channel and could go no further.

Then there is the bit where the First Battle of Ypres happens. The familiar English-language story is that the Germans smash into the BEF with particular force on 31st October, create an opening to Calais, the Worcesters come and save the day and then the boring, trenchy part of the war starts. None of these things are untrue, but that’s a third of the story of October 1914. There’s a slog going on up to the coast where the French and the Belgians are fighting just as hard on the Yser, and then, to the south, the massive bulk of the French Armies is also still hard at it. That’s where I am heading today, ostensibly so I can tell you all the story of one of my heroes…

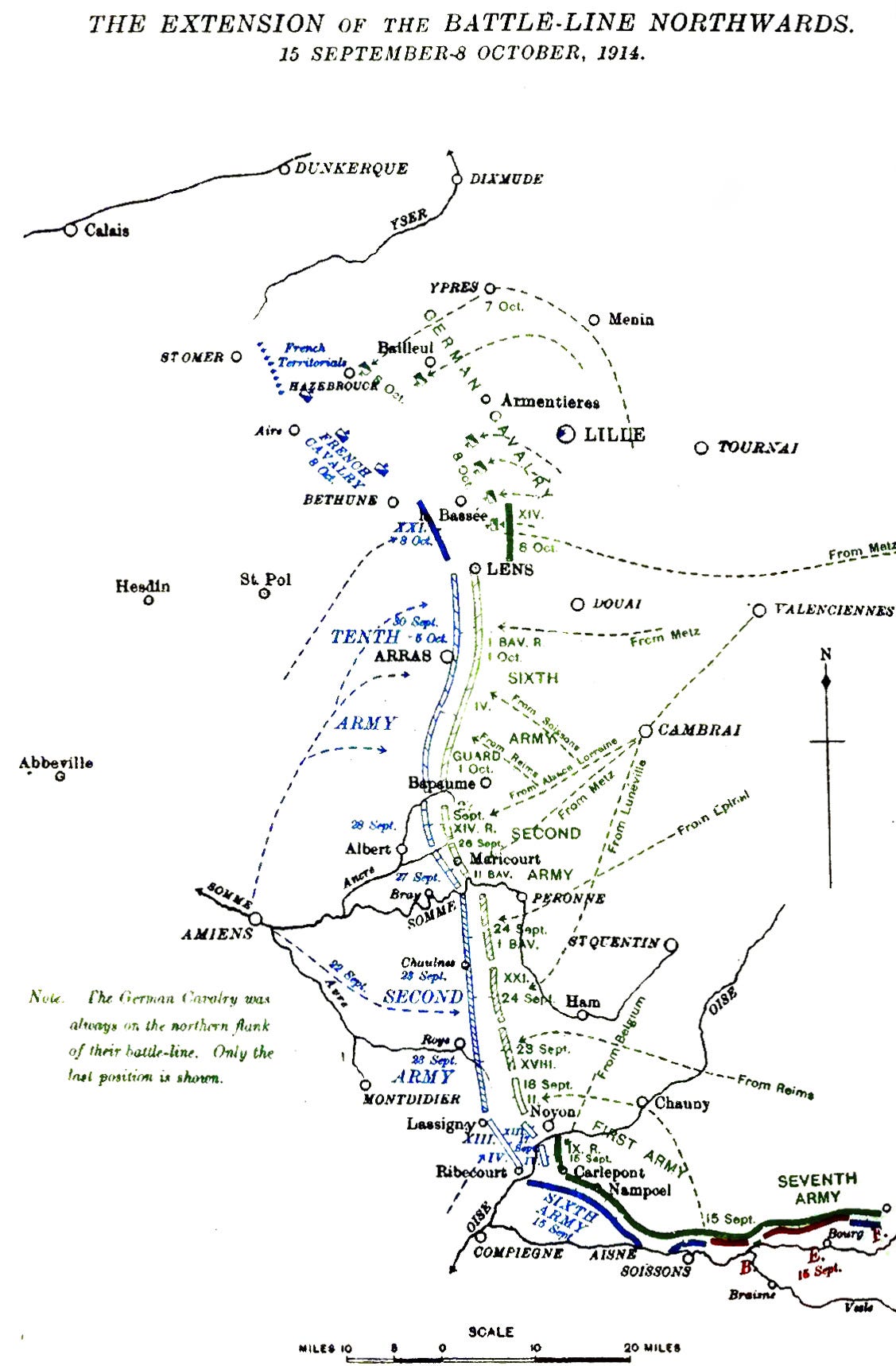

A broad outline of the ‘Race to the Sea’ (British Official History)

France Under Fire

We now know, with hindsight, that all of this manoeuvring was essentially sketching out the line that would become the Western Front, but at the time, everything was in flux. Both sides were fighting the last encounter battles of 1914; scrapping wherever they smashed into each other as opposed to launching big, static offensives on heavily entrenched positions like the ones that were about to come.

As both sides chased each other north looking for that chance to outflank, the French came across the first stages of wholesale destruction that would ravage their country before November 1918. At the end of September, General Joseph Joffre, a portly officer from the Pyrenees in overall command of the French, saw this damage for himself on the way to see one of his subordinates:

‘Almost all the villages were destroyed by the bombing or the fire that the Germans had started when they left. The road from Fère-Champenoise to Châlons crossed a huge cemetery. In the woods which ran along the railway line… as far as the eye could see we observed large tombs all white with quicklime: kepis, jackets, weapons were hung on hundreds of small cross at the foot of which pious hands had placed wild flowers. Between Epernay and Reims, the roads were broken up, the mile markers and the telegraph poles torn down; carts, cars of all kinds, even cabs that had come from no-one knows where, lay torn apart with their wheels in the air, car chassis formed immense piles of scrap metal; only the vineyards, by some coincidence, seemed to have suffered little. East of Reims, I visited some batteries. The city was still almost intact, but the cathedral, which the enemy had, in violation of international law, savagely bombarded on 19th September, had been set on fire, and had already suffered irreparable damage. The war was barely two months old, and we could already see the accumulation of ruins our victory over Germany would cost.’

Marechal Joffre, the man tasked with saving France.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Alex Churchill’s HistoryStack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.