I have mounted my soapbox and nobody is shutting me up. This is my day, dammit. Time, and time (and time) again, I read the same tired tropes surrounding this monarch. Frustratingly, they come from people attaching themselves to negative opinions they think are sound, having read nothing written in the last four decades. When I started working on George V’s private papers in large quantities in 2015, I was one of two historians simultaneously granted access by the late Queen. We were the first since before I was born. That’s some pretty dated/ropey scholarship to base your perception of someone on.

Also, I’m going to be blunt, if you are taking your history from sources that exclusively been generated by, or have passed extensively back and forth through the Duke of Windsor, his eldest son, then you are in trouble. Because he actually didn’t have much negative to say until he abdicated and became a bitter and twisted freeloader with a grudge against his family, and at no point was he ever a sensible barometer of opinion about anything important.

As every mailing list on the planet keeps reminding me, Father’s Day is later this week, so I’m going to focus on one thing today:

George V was not a sh*t parent.

To quote the late Philip Larkin, in the only poem I know from memory, titled This Be The Verse:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

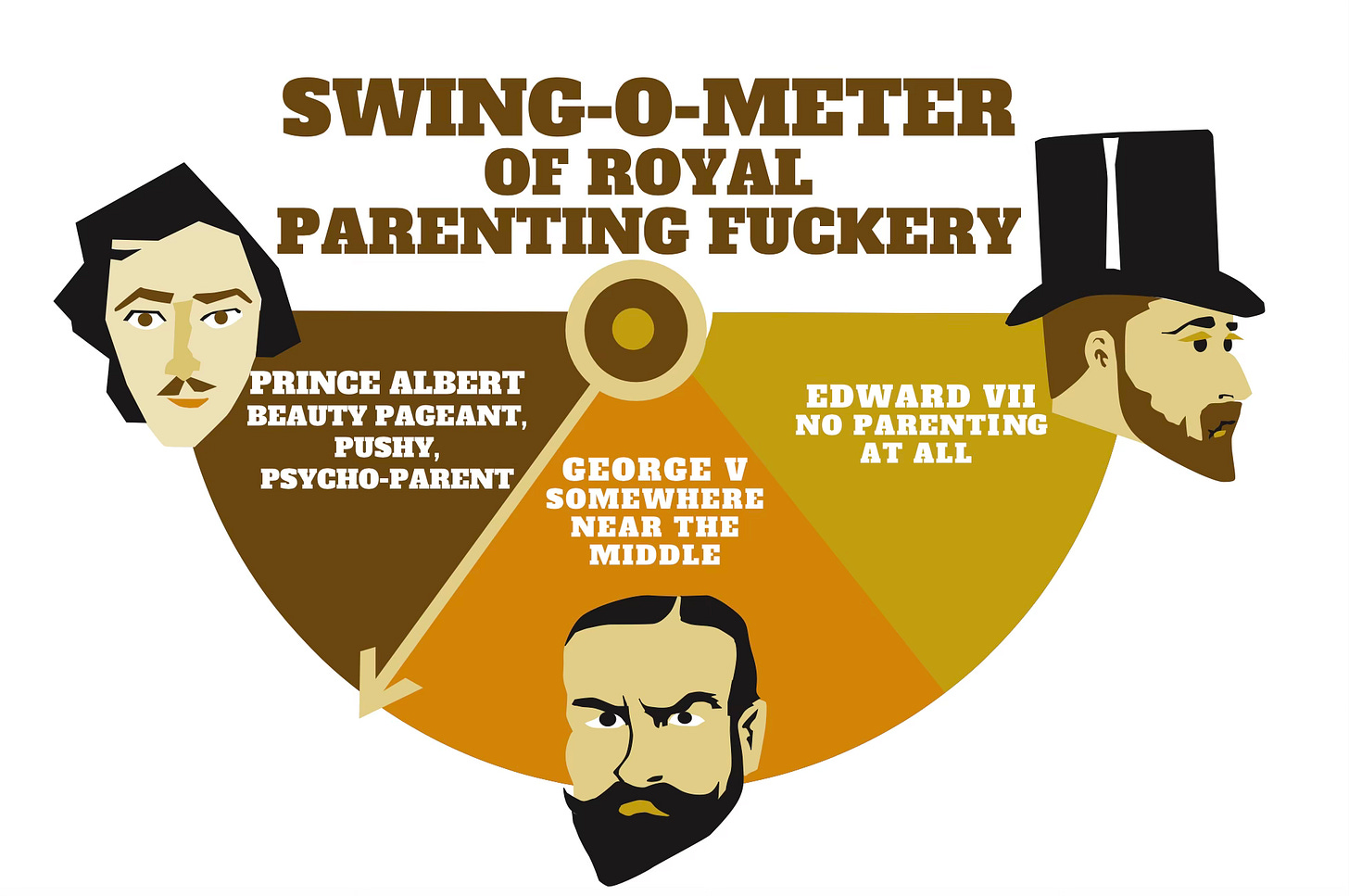

Deciding to skip parenthood is not an option if you’re two deaths away from the throne, but as Larkin points out, not a single one of us isn’t damaged. The 19th and 20th centuries British royals swung between ridiculous berating of their children, to all out anarchy when those children went on to produce offspring themselves and dispensed with discipline completely. Behold, the ones that matter for the purposes of this article:

(Steve Smith/Alex Churchill)

Without going into too much detail, Prince Albert designed a schedule of education that was oppressive. If the kid was bright, they could attain excellent results, and he did all of this with the laudable intentions of sending nearly a dozen princes and princesses out into Europe to make the world a better place. (More liberal, because that was his thing) His eldest child with Queen Victoria, Vicky, was very bright and fared not too bad. Their second child, the heir, ‘Bertie’ was not bright at all, and for him, the regime was a disaster. He spent his entire childhood being berated by his parents and told he wasn’t good enough. If nothing is ever good enough, and the criticism is forthcoming anyway, then what’s the point in trying? Edward VII’s subsequent philandering and all the mayhem he put numerous women through owed much to his upbringing.

When he became a father, firstly to Prince ‘Eddy’ and secondly to the future George V, he let his kids run amok. ‘Georgie’ used to run around the palace kicking the servants in the shins. As for education, the structure was a shambles. Again, if your kid is smart, or at least sensible, they will probably make out okay. This is what happened with George, who may not have been a genius, but he was sensible. (It makes me lol when people call him thick. Know why he didn’t speak any German? Because nobody cared enough to teach him. Know what he did speak competently when he made the effort to learn later on? Sufficient Hindustani to show wounded soldiers the courtesy of at least asking how they were doing in their own language.)

So what does George V do when it is his turn to produce a generation of royals? He swings back somewhat towards the middle. Because before he died of the flu, his elder brother was a sadly slow-witted, unmitigated, sometimes-gonorrhoea-addled disaster and things like the lack of German? George didn’t want his kids left in the same unprepared position he found himself. Also, having watched his dad and his brother shag their way around Europe with embarrassing results, (he was still dealing with one scandal after his father died in 1910) he was not about to see his own heirs end up the same way. Time to take a deeper dive…

Parental ogre George V with his eldest son, the future Duke of Windsor c.1897. Most of the Duke’s harsh criticism of his father came after his own abdication, when he had fallen out with his brother and was embittered about the (apparent lack of) free money he was being given. (Royal Collections Trust, via their website)

Over the years, the image of George V as a Dickensian villain has been adopted in terms of his role as a father. He has been described as a thoughtless bully; and Queen Mary as a cold and unfeeling mother. Nope, and er, nope.

David’s evidence is questionable

Prince Edward, known in the family as David, is not a reliable witness because rampant narcissism and self-pity tends to skew your perspective. Much of what he wrote about the flaws in his upbringing, which forms the bulk of the evidence against the King and Queen, was penned half a century later. In the interim, much troubled water had passed beneath that particular bridge, including his abdication, exile and his dissatisfaction about his subsequent settlement. Even then, he admitted he had never wanted for affection. He even wrote that Sandringham had been idyllic. George V taught his sons to shoot when they were thirteen. “He laughed and joked,” David recalled, “and those ‘small days’ at Sandringham provided some of my happiest memories of him.”

Though the children were encouraged to be modest and thoughtful, they were not denied. Christmas and birthday presents were lavish. When Prince Harry advised his parents that he would need to adhere to a school tradition and provide a birthday cake on his special day to be shared among the boys at his table, a cake arrived “which happened to be so big,” Harry wrote to the King and Queen, “that I had to give it to the whole school instead of one table otherwise I would not have finished it at the end of term.”

The children were not oppressed, or ignored

All of King George’s sons were pranksters as children and they harboured no fears about making their father a victim. One day they watched, apoplectic with glee as he began stirring his tea and the spoon simply dissolved in the cup. Obtained from a joke shop and made of an alloy with a low melting point, antics like these do not suggest children under a terrifying yoke. Neither do children who live in fear of their father engage in full-blown food fights in front of him.

Simple domesticity was a marked, undisputed feature of King George’s reign, and you can’t achieve this if the kids are never in the picture. For part of the year, all eight family members were even crammed into tiny York Cottage, through choice. How distant can you be when you’re physically tripping over each other? One of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting wrote that although the King and Queen had been depicted as distant parents, “this they most certainly were not... I believe that they were more conscientious and more truly devoted to their children than the majority of parents in that era.” Match this up against the Kaiser in Germany at the same time. His children were sent away far more often, and to see their father, they apparently had to make an appointment.

Actually, George V was intensely interested

Unlike his two elder brothers, Prince Henry was sent away to school and this filled the King with interest, for it was a world that he had never experienced. He wanted to know all about it and complained that his son’s letters were not detailed enough. He wanted this insight to his school life: “What you do, the people you meet and who your friends are and who do you fag for?” He was similarly interested in Prince George’s prep school days.

He tried to get closer still to all of his kids

The King took pains to try to be more demonstrative with his children. He was not great at showing affection, and he knew it. After two boys, he was desperate for a girl by the time Princess Mary arrived in 1897. Faced later on with the terrifying prospect of a teenager, he didn’t quite know what to do to improve his relationship with his shy daughter. When the two found themselves without the rest of the family for a snatched few days at York Cottage, Queen Mary was quick to orchestrate a way for them to spend some time together. “I have written to Mary and begged her to... ask you whether she may sit in your room if she will not be in your way. She would never dream of doing such a thing of her own accord.” The King was extremely proud of the result. “I have invited her to come and sit in my room while I write, she is just coming now, and seems pleased at the idea, although, she doesn’t talk much, at least to me, but that will come I hope.”

By 1914 they rode every morning together. When David teased his sister about being necessarily stuck with their parents as a young girl, while he and the rest of her brothers were out in the world, she replied: “You need not feel so sorry for me.” The only thing she minded were dull dinners on occasion when the King would sit and read his paper and there would be no conversation.

He’s a proud father

Bertie was an excellent shot, and their shooting was a bond between them. When Harry too began to show promise, the King was thrilled to receive a letter saying that he had shot his first stag. “I hope it was a good one, write and tell me all about it.” They spent an afternoon at Sandringham together soon afterwards and His Majesty was “frightfully pleased” to be shooting side by side with his improving son. When the King was unforgiving, it was arguably because he did not want his children to encounter the same difficulties that he had had to contend with, physically as well as in terms of education. George V was somewhat knock-kneed, and he went to extreme-sounding lengths to try and make sure that his sons did not grow to adulthood with the same affliction. Both Bertie and Harry were obliged to spend portions of their childhood sleeping with leg splints on and wearing them for spells during the day too. It made them miserable, but the King was unmoved. On one occasion he found that the boys’ personal attendant had given in to Bertie and removed them. His Majesty promptly sent for the servant. “Drawing his trousers tightly against his legs to display his own knock knees, he said sternly: “Look at me. If that boy grows up to look like this, it will be your fault.” Both boys adhered to the regime and neither grew up with their father’s affliction.

But he’s not as pushy as you’ve been led to believe

George V was nothing like Prince Albert, who wanted perfection. Yes, George V was determined that when his children become of an appropriate age, they would be ready for the public life and the duty that awaited them. They would, after all, become part of a unique family business. He had been expected to prop up his weak elder brother Eddy throughout his entire youth, and that left a mark. George V was not educated or prepared to rule when his brother died and elevated him to the direct line of succession and he was, understandably, insistent that this would not be the case for his own heir. When the King and Queen settled on Eton for Harry, he had to undergo rigorous schooling in Latin verse to gain admission, because until then the King had been insistent instead that he, along with his siblings would be able to speak French and German, which he was not able to do with any fluency because modern languages had been neglected in his own schoolroom. By the time he was sent away as a young man to perfect French and German, he only managed to advance with the former. Trying to learn German as an adult, he could never wrap his head around it.

But even though the King was firm in respect of what he wanted to prescribe for his children, his rebukes when they failed him were by no means as harsh as has been implied. Once, when Harry missed the train back to school he simply remarked that it was because he was “always so vague about everything.” When George managed to dislocate his knee playing French cricket at school, his father’s only criticism was that he had never heard of such a thing, and that he “thought it was bound to be a silly game.” Far from being over-demanding in respect of his children’s abilities, mediocrity was enough. Queen Victoria’s offspring had been subjected to that endless barrage of criticism, but as long as his children tried their best, George V was satisfied. When Bertie did badly, the King’s preoccupation was not that he was not the brightest boy in his class, it was that he had been informed that his son did not take his work seriously. Praise was forthcoming when he pulled himself together. “We are glad to hear that you have done well in French lately,” Queen Mary wrote to him in 1909, “and on other subjects too, this is a great thing and shows you are taking more trouble with your work.” At the time he was still practically bottom of his class. When Harry finished halfway down his division at Eton, his father was pleased, because it “was quite credible and shows what you can do if you like.” To Prince George he once wrote: “So your exams begin today, I hope you will do well in them and gain some places in the order.”

More than anything the King wanted his children to be good people. George V and Queen Mary ensured that their brood was both polite, and that they lacked any semblance of arrogance given their privileged circumstances. Once, when he was riding with two of his sons in Windsor Great Park, the boys over-exuberantly cantered past two labourers on the side of the road, who had stopped to salute the royal riders, without acknowledging them. “At once their father halted them, wheeled them round, and made them return to the two astonished men, who received elaborate apologies from the boys for their unintentional rudeness.”

George V acts as chief mourner at the funeral of the unknown soldier on Whitehall in the early 1920s. The future George VI watches on. At the time, as a second son, he had no expectations of becoming King.

Blunt, yep. Also, the banter could be too much

The King could be overly blunt in dealing with kids. As a boy, his naval service had instilled in him an obedience to authority which in turn, he expected to receive. He could be loud, brusque, and angry. And so to his small children, yes, he could be formidable. He could also be a little thoughtless as far as their sensitive young minds were concerned. His dry sense of humour could come off as more insulting than was intended. On one occasion, his third son, Harry and a friend had decided that they would build an aeroplane. The King, who never would go up in one even if he did come to admire them during WW1, informed him brutally that “neither of you will attempt to fly in it, as I am sure you would both come to grief.” This chaffing was part of King George’s own upbringing, the inevitable result of a youth spent in service of the Royal Navy receiving no special treatment. Once, on a shooting excursion at Sandringham, a local boy was given the King’s snack by mistake, and he forever mocked him as “The Boy Who Ate My Sandwiches.”

Parenting royal children isn’t normal

The King never forgot his responsibility in terms of preparing the next generation of royals. “I trust that you will always remember,” he wrote to David when his eldest son became Prince of Wales, “that now you must always set a good example to the others by being very obedient, respectful to your seniors and kind to everyone.” The King was devoted to his duty, and expected the same of his family, especially his heir, to whom he would bequeath an Empire, but he did not bully his children into submission. George V was a moderate blend of both his grandmother’s severity and his father’s reactionary parenting, which instilled almost no discipline at all, yet with similar results.

By 1918, Prince John was the only one of His Majesty’s children not in uniform. Prince George had begun his journey into the Royal Navy, making several official visits in the company of his parents. Prince Henry finished his first term at Sandhurst in the summer. With his mother and sister, he had visited a projectile factory just after his 18th birthday; before spending Easter Monday with workers too, those at Vickers who have given up their Bank Holiday. “He took on no airs and assumed no privileges, he remained, in fact, entirely modest.”

But Princess Mary had been perhaps the most surprising revelation so far during the war; taking advantage of all of the leaps and bounds made by the nation’s young women as a result of the conflict. She had not long turned 17 when the war commenced and was immensely shy. Her role was limited to being her mother’s right hand in Queen Mary’s war work. She soon began training as a nurse, and as a probationer at Great Ormond Street asked that she receive no special consideration at all. She worked two mornings a week there, making her parents distinctly proud. The Queen has seen her in action and proudly tells the King that she is an exemplary nurse, “which I am delighted to hear,” he replies, “but she is a curious girl, always so reticent and never tells one anything. I expect she has much more in her than one thinks.” He was as good as reading his children as he was his people.

Some visits were still in the company of her parents, and the King did all he could to try and bring his daughter out of her shell. During a visit to a Walthamstow motor lorry works, he was conversing with a forewoman when he saw that Mary had become a little detached from the group. He excused himself briefly and went to fetch her. Leading the Princess gently by the arm he introduced her with complete informality as “my daughter” and brought her into the conversation. She may have been shy, but Princess Mary had her father’s memory for faces, (Queen Elizabeth II had it too) and she was bright, very much her mother’s daughter.

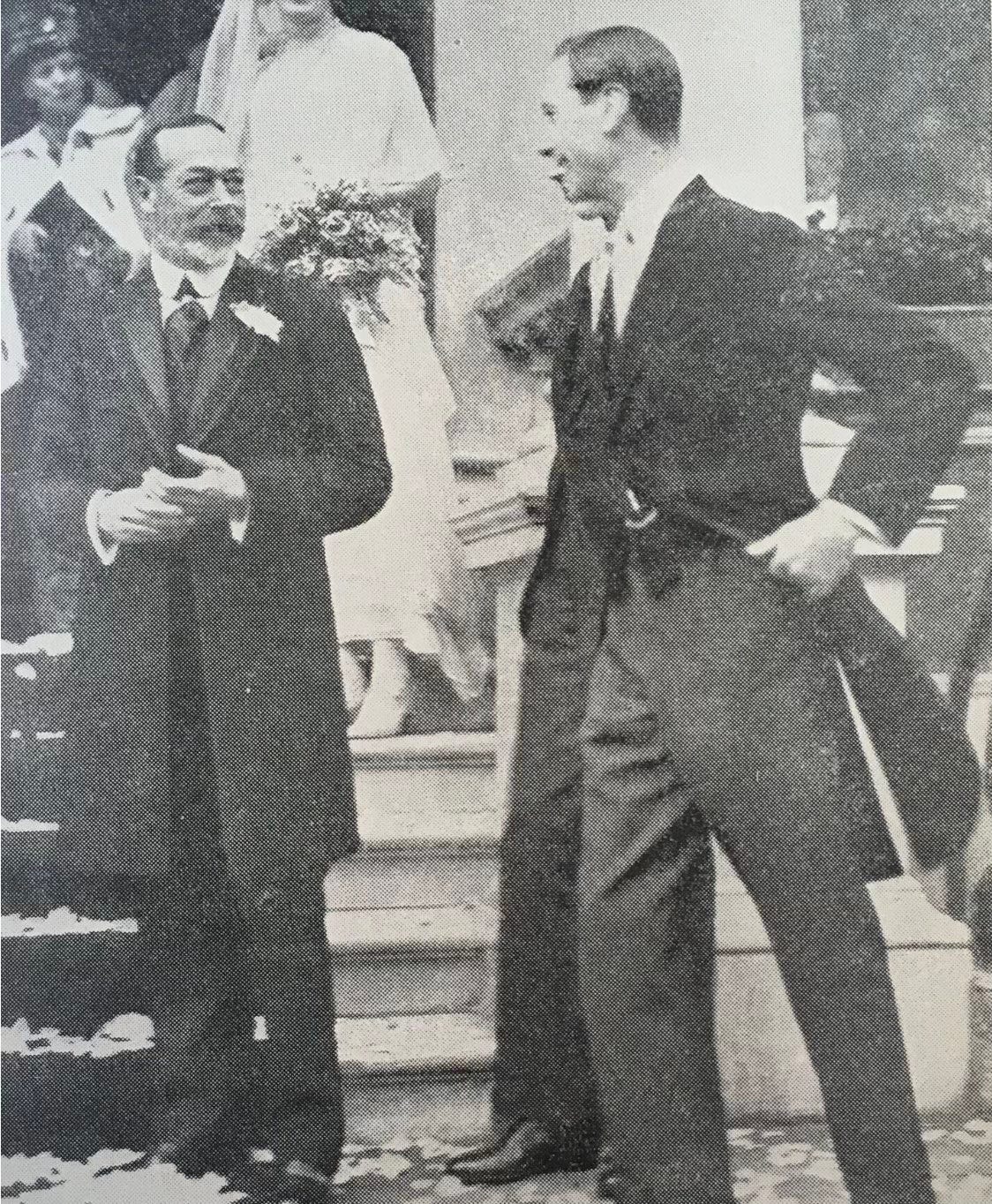

George V shares a joke with the future George VI on his son’s wedding day. In his personal and professional life ‘Bertie’ stayed close to the example set by his one father.

So there you have it. I’ve not even got to the King and Queen’s developmentally challenged youngest child, Prince John; Johnnie. That’s a whole article on its own someday to do him justice. As historians we’re taught to look at the evidence. So far, the documented evidence I have shows me that:

George V wanted his kids to be better educated and prepared for their official lives than he was.

He wanted them to be good people

He got pissed off on occasion and shouted them.

He was terrified by his teenage daughter and solicited advice to get her to open up to him more. Queen Mary’s brilliant advice amounted to (paraphrasing): Start a conversation with her, she’s not an alien.

He got frustrated when he thought that his children were either not trying, or that they were being their own worst enemies. In the case of the Duke of Windsor, all of his fears were confirmed, but he didn’t necessarily express his frustrations in the best way. He was known to lose his temper.

He was not bored by his children. Anyone taking paternity leave to dote on his wife and baby number six is not disinterested in his offspring. If he did want to be with them, he wouldn’t have insisted on spending months crammed into a cottage with them when he owned the mansion next door.

If anything, as they reached adulthood, as opposed to wanting rid of them, George V was too clingy, and courtiers closest to him intervened. Essentially: They don’t want to spend every night on the Western Front hanging out with you post-armistice. They want to go and get shi*tered with their friends.

I did not have a good father. Doesn’t make him a bad person, but it means I know a failure when I see one. I’d have chewed your arm off to have a slightly clingy George V annoying me about whether I’d done enough French practice and trying a little too hard to ensure I stayed STD free. In fact, I’d have given anything just for bullet point number four. Was George V perfect as a father? No. Newsflash, neither is anyone else. Did he parent his kids in the best way he believed he could? Yes. That’s all he asked of anyone else, including his children, and so it’s all I ask of him in making my judgement.

Thank you Alex, wish I had this insight into parenting 30 years ago. A brilliant piece, full of verve and love for Bertie. X

Very good. Tiny bit off topic. I think one of the great what ifs of history concerns the brevity of the reign of Kaiser Frederich III. Had he lived as long as his father would we have avoided the FWW and the ensuing catastrophe caused by the fall out of that war? Would Fritz and Vicky remade Germany into a more liberal nation?