The historian… must always maintain towards his subject an indeterminist point of view. He must constantly put himself at a point in the past at which the known factors still seem to permit different outcomes.

If he speaks of Salamis, then it must be as if the Persians might still win....

Johan Huizinga, The Idea of History

I completely subscribe to the above concept. I said it earlier in the week, but as opposed to minutely analysing why and how great events happened, one of the things I like most about my job is putting people back somewhere in time, before my characters know what the outcome of events is going to be, and bringing their experience back to life for a reader.

Today, Ring of Fire is finally published, and I want to do two things. Firstly, explain a bit about how it came to pass, and secondly, give you a sneak preview of exactly what I am talking about above.

Way back in the first lockdown we were busily putting out about eight episodes a week of History Hack when we came across a complete nerd in Copenhagen who was obsessed with the Austro-Hungarian army in the First World War. At about the same time I decided, out of complete boredom, to do something about my shoddy foreign language ability, which dates back to getting an E for GCSE Spanish and being told, exact words, that I was a moron. I paid for a Duolingo subscription and began obsessively working on my almost non-existent French for something like two hours a day. Then added Italian.

Anyway, fast forward a few months, the nerd, Nicolai, had become a friend and we both became heavily involved in the newly launched Great War Group. We began talking about whether or not you could still write something completely new about the First World War 110 years on. Nicolai’s absolute bug bear in First World War historiography is The Guns of August. It’s not that he doesn’t like the writing. It’s not that he thinks it’s a bad book, but he feels it’s wholly weighted towards what happened in the west in the opening weeks of the war, and that half a century on, something should have at least refreshed the concept of a singular volume on the outbreak of war to challenge it.

So we started talking about what this update might look like.

We believed that for it to be radical enough, you would need to do several things. Firstly, you would need to smash the boxes. No more Western Front, Eastern Front etc. We believed that when you write inside the boxes, you lose the interplay between them. No one thing happens on one front without impacting another, and when you stick to your box, that inevitably gets less attention.

The next thing we thought was necessary was making it nation blind. Everyone would have to be in their proper context, with the proportionate coverage according to their contribution to the war at the time. That way, you could pick it up and put it into any language and it would remain fair. The key thing here is that we, well more I, was going to have to concede that this meant talking a lot less about the British when it came to the fighting. 60,000 Tommies vs. millions of French and Germans in the west makes it essential. This also meant wholly embracing the foreign language aspect. Now, Nicolai obviously speaks Danish, but he also studied in Russia, which meant he not only had Russian but could muddle along with most Cyrillic script to find what we needed, and he had learned German in order to obsess about the Austro-Hungarian army. For my part, I had been bashing away at both French and Italian. Luckily for all of us, the Spanish required was an absolutely minute component of what might be required and google translate exists.

The last thing, and it was a big one, that we thought would make a project like this special, would be to write it from the bottom up. That’s hardly anything from Kings, presidents, and great white men, and instead, a narrative built on the testimonies of ordinary people. As well as that, we wanted more from civilians, women, children and the elderly. Most of all, more from countries that were neutral. Because they didn’t exist in a vacuum for four years.

So it wasn’t going to be easy. We were deliberately dismantling the neat boxes that make this stuff manageable to deal with in size, but we resolved to start and see where it went. Luckily, my agent believed in the project, and despite the fact that this was not about the shiny sequel war, we found a publisher that believed in it too. As for the title, the people in the book chose it for us. You’ll see, when you read it, but multiple witnesses all over the globe referred to August and September 1914 as like being trapped in a ring of fire.

I couldn’t have asked for a better co-author. We have nothing in common within the war in terms of interests. He doesn’t do sand. Or boats. I don’t do the Eastern Front or the Balkans. In the West, he does the German and I do the French, so that when you mash us together you get a rounded picture. It was a level field in terms of effort, too. More of the translation fell on Nicolai, and more of the editorial work fell on me; because English is my first language.

I think we had a conversation at some point about how if we were going to properly smash the boxes, and break down the language barriers, this was going to be the hardest thing we’d ever done. Nearly five years after we met, I think we’d agree that we were not wrong. Remarkably, we haven’t had a single fight in putting this together. The one, mutual meltdown we had at his kitchen table when we got to the Battle of the Marne and everything was in a foreign language and we just, didn’t, wanna; his wife put us in our place and told us to get over ourselves. Thanks Linda.

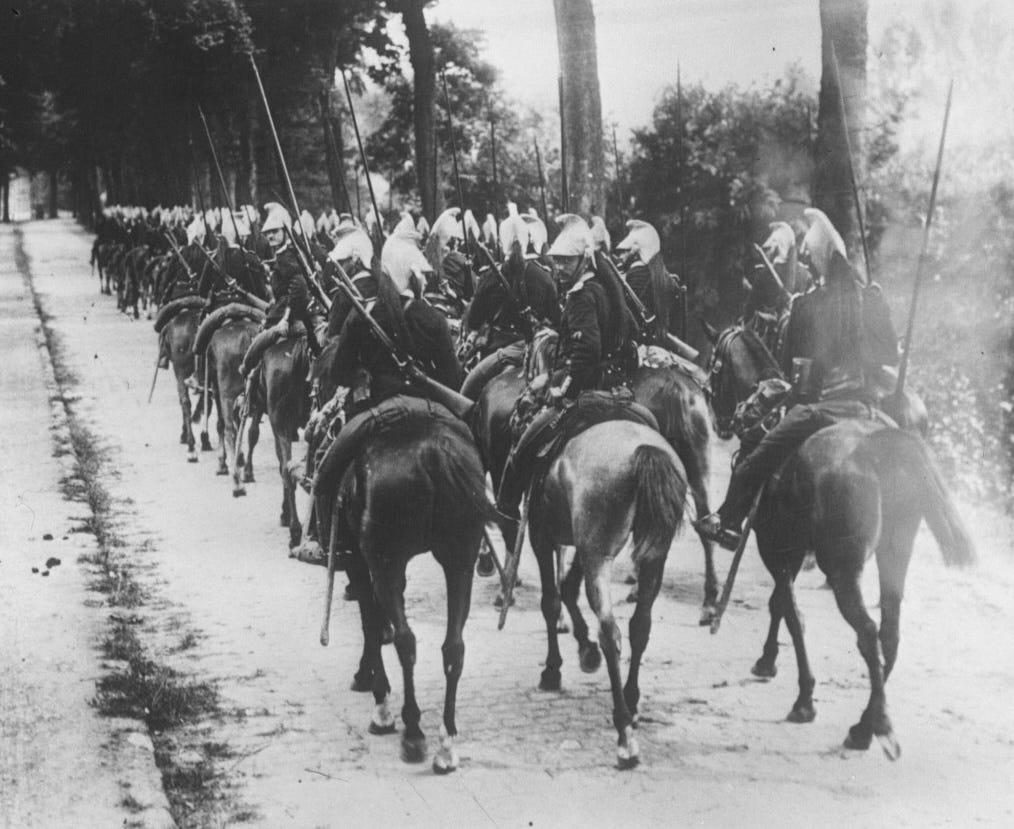

French cavalry on the Marne, September 1914. (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

We had to get good at setting the scene, explaining the context and then zooming in, right to ground level. That’s what this excerpt is about. Picture the scene at the beginning of September. An exhausted French cavalry unit has been on the run from the invading German hordes for weeks. They have retreated so far, that they are only a few miles from the Eiffel Tower. In the plot, we’ve reached the eve of the Battle of the Marne. This is France’s one chance to avoid defeat and total, humiliating disaster.

Marcel Dupont and his comrades were about to get a surprise when their colonel lined them up with a piece of paper in his hand. 'Men and beasts were half asleep,' he wrote.

On hearing the first few sentences we drew closer around him as by instinct. We could not believe our ears... Had we not been told the day before... that we were going to retire to the Seine? And now in a few... simple words the Commander-in-Chief told us that the trials of that hideous retreat were over, and that the day had come to take the offensive.

Dupont was ordered to examine a road leading to the village of Courgivaux. He chose his men, 'a corporal and four reliable fellows who had already given a good account of themselves'. Right out in front rode a trooper by the name of Vercherin, mounted on his faithful horse Cabri. Dupont had complete faith in him. They had already learnt the hard way that they had to spread out. ‘We knew what ravages they made [if] our troopers were imprudent enough to cluster together. Up ahead the road became dangerous. I called out to Vercherin to stop. None of this new, cautious way of doing things made Dupont's heart sing:

How much more dashing it would have been... to ride full gallop, brandishing my sword... into the nearest copse! But I knew then that if it were occupied by the enemy, their men would be lying down, buried in the soil, using the trees and bushes as cover, till the last moment. Then not one of us would have come out alive... The good old times of hussar charges are gone, together with plumes, pelisses waving in the wind... It would be senseless to continue to be a horseman in order to fight men who are no longer cavalrymen and do not wish to be so.

Courgivaux itself appeared deserted. No locals, no enemy defences. In front of them 'a large farm protruded, like the prow of a ship'. The silence was almost worse than the noise of a battle.

Suddenly Dupont saw Vercherin stand up in his stirrups. ‘I understood that he saw something, and I galloped up to him at once...

"Mon Lieutenant... there behind that stack... I thought I saw a head rise above the grass.”’

Then their horses were startled, 'suddenly seized with a simultaneous terror'. As he raised his glasses, Dupont saw them, less than 100 yards in front:

A whole line of sharpshooters, dressed in grey, rise quickly in front of me. For one short moment a terrible pang shot through us. How many were there? Almost at the same time a formidable volley of rifle shots rang out. They had been watching us for a long time. Lying in the grass that lined the road leading to the farm or else behind the stacks... Not one of them had shown himself... We had to be off.

On Dupont's signal they galloped away. 'I suddenly saw to the right of me Ramier, Lemaître's horse, fall like a log.’ He saw horse and rider flail on the ground, 'forming a confused mixture of hooves in the air and waving arms'. Ramier got up and limped off. As for Lemaître, he was on his feet, setting his battered shako back on his head. The trooper skipped to safety, 'striding along with his short legs and heavy boots, jumping ditches and banks with a nimbleness of which I declare I should not have thought him capable'. A comrade managed to catch Ramier. 'It was painful to see the poor animal,' wrote Dupont. 'His lameness had already become more marked. He could only get along with great difficulty, and his eyes showed he was in pain? They established that Courgivaux was impassable and there was nothing they could do for the horse.

‘Lemaître was standing in great grief over poor Ramier, lying inert on the ground and struggling feebly with death. His eyes were already dull and his legs convulsed. Every now and then he shuddered violently. I looked at Lemaître, who felt as if he were losing his best friend. I dismounted...

“Don't grieve, my good fellow; it is a fine end for Ramier. He might, like so many others, have died worn out with work or suffering under some hedgerow. He has a soldier's death. All we can do is to cut short his sufferings and send him quickly to rejoin his many good comrades in the paradise of noble animals.”'

Lemaître looked utterly unconvinced as Dupont pulled out his revolver. His hand was shaking:

‘One less horse in a troop is the same as one child less in a family. And, besides, it means one trooper unmounted and the loss of a sword in battle. Lemaître was right. Ramier was a good old servant, one of the kind that never goes lame, can feed on anything or on nothing, and never hurts anybody. It was hard to put an end to him; but since he was done for, I put the muzzle of my revolver into his ear. I did not wish him to feel the cold metal; but his whole body shuddered, and his eye, lighting up for a moment, seemed to reproach me.

Paff!

A short, sharp report, and Ramier quivered for a moment.

Then his sufferings ceased, and his stiffening carcass added one more to the many that strewed the country.’

One of my favourite bits of the book is going up and down the line two chapters later, including to another cavalryman, as the French begin realising they have won on the Marne. I can’t read those accounts without wanting to cry, because of the overwhelming sense of relief and joy you can feel coming off the page after you’ve watched them suffer for several chapters. I’m not going to post that here though, because it will ruin the suspense we’ve worked so hard to create.

Ring of Fire: A New Global History of the Outbreak of the First World War is published by Head of Zeus and it is now available to buy. (£30 rrp) There are multiple options to purchase, including an audiobook I recorded myself here:

It is released in North America on 5th August.

I was lucky enough to be given an uncorrected proof to review for Salient Points - the Great War Group’s quarterly magazine. Alex and Nicolai really did a masterful job with this and fully hit the brief they set themselves. It’s a book that deserves to be on everyone’s bookshelves.

This looks absolutely fantastic, Alex... Looking forward to reading more once I get my hands on a copy. 👍📖

A hearty well done to you and Nicolai.