Today I’m sharing my second book recommendation for the week, before normal service is resumed next week with my monthly feature in the shape of a slice of American pre-WW2 history.

On Tuesday I went forward from the First World War with an exclusive look at a new book examining the fallen Hohenzollerns and their ties to the Nazi regime, and today, I’m heading in the opposite direction with a prequel of sorts.

Today sees the launch of Chain of Fire: Campaigning in Egypt and the Sudan, 1882-98 by Peter Hart. I’ve forgiven him for almost nicking our book title because I really like this. What we’re looking at is a new framing of some of Britain’s imperialist past and the latter stages of the scramble for Africa. What Hart’s done, is not only look at why Britain felt the need to get involved in Egypt, and how this was an outlier of sorts in imperial influence, but he also shows how aspirations in the region came tumbling down thanks in part to the idiocy of General Charles Gordon. What’s new about this book, is that he then carries the story through with the redemption arc that Hollywood loves and brings the narrative all the way up to the bit where Kitchener inherits the “of Khartoum” part of his name and settles scores.

We’re having a launch event tonight, and I’m going to be doing something else that Hollywood is obsessed with: origin stories. Because within the pages of this book you also get the early careers of a number of First World War generals; when they were much less grey, and occasionally even handsome. Pete will be giving a talk on the scrap at Atbara, and I’m sure if you ping one of us a name you’ll be able to pay on the door and join in. You get a copy of the book which he will undoubtedly sign (usually against your will) with your ticket.

For those that can’t make it to East Finchley, however, I’m going to give you a taste of the book. Often I give you the introduction and then leave you to discover more on you own, but today, I’m going to leap into the middle of the action. To set the scene, it’s the end of 1884. Against instructions, General Gordon, who was supposed to be on a fact-finding mission, has taken root and gone and got himself trapped at Khartoum. After a lengthy bit of prevarication, the British Government has decided that someone should go and fish him out. Sir Garnet Wolseley is placed in charge of this slightly half arsed rescue mission, and decides that his entire force winding their way to Khartoum along the Nile isn’t going to suffice…

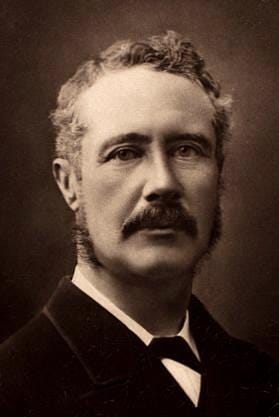

General Charles Gordon. My nan would have referred to him as ‘a wally’. (Wikipedia)

Delays breed more delays and there was soon no doubt that despite Lieutenant General Garnet Wolseley's efforts to chivvy things along, it was evident that his secondary plan of an overland Desert Column in addition to the river route would indeed be necessary. He had to get a force to Khartoum by the quickest possible method, but time was fast running out. Gordon's messages were more infrequent and by December 1884 it was evident that he could not last out much longer. The river route would still be central to Wolseley's plans, but a corner had to be cut - literally and figuratively.

His new plan was for a River Column based on four infantry battalions to push up the Nile with their whalers by the circuitous route via Abu Hamed and Berber as originally planned under the command of a gruff experienced old campaigner, Major General William Earle. Meanwhile, a smaller, but supposedly fast-moving Desert Column, under the command of Brigadier General Herbert Stewart, would march the roughly 175 miles across the open Bayuda Desert to the vicinity of the Dervish-held town of Metemmeh which they were to capture.

Here they would rendezvous with Gordon's surviving river steamers, who would carry the chief intelligence officer, Colonel Charles Wilson, to meet Gordon at Khartoum, so that he could report back first-hand on the real state of the siege. Meanwhile, Stewart would organise supply columns and stores depots back along his route across the desert, while awaiting the arrival of the River Column. In hindsight, there was a great deal wrong with this plan, but at the time there was a mood of optimism in the Korti camp as Wolseley arrived and the Desert Column readied itself for its departure.

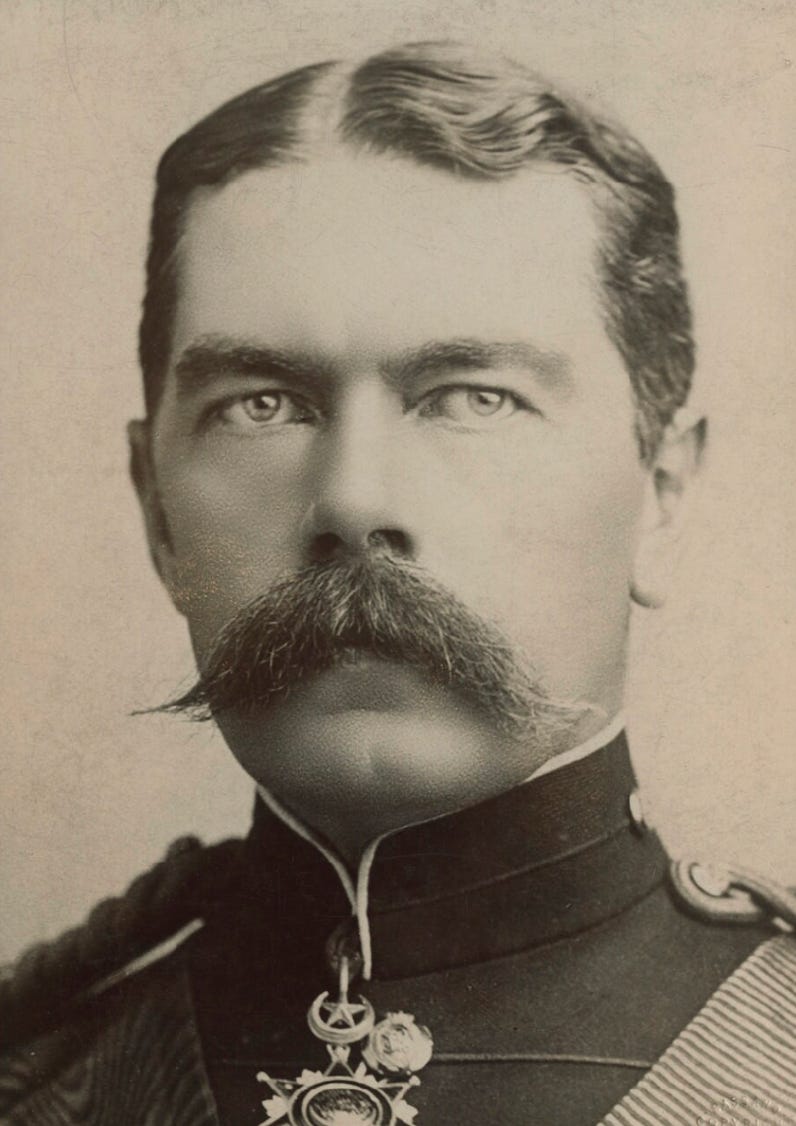

‘Lord Wolseley arrived here just at dusk I was on the bank in a crowd of soldiers and officers - almost the first thing I heard was Lord 'W' saying, 'Is Major Kitchener there?' Then someone said, 'Yes!' and he then said, Let him come on board at once I wish to see him!' I had to go down a broad flight of steps and on board he shook hands and asked the news which I told him. Next day I met him walking about and he called me and said some very nice things about my services - I dined with him the same evening. However, the greatest honour was done to me last night, Xmas, the men had a bonfire and sang songs - Lord 'W' and everyone was there. After the songs cheers were given for Lord W', General Stewart, and then someone shouted out, Major "K"!' so 2,000 throats were distended in my honour. I am very proud of that moment and shall not forget it in a hurry - after that General Buller was cheered - I expect we shall be at Khartoum before you get this letter.’ - Major Herbert Kitchener, Headquarters

Kitchener, whose name would become synonymous with Khartoum (National Portrait Gallery)

It was not to be.

At 15.00 on Tuesday 30 December the Desert Column set off from Korti after a march past Wolseley to bid them on their way. By this time, it consisted of the Heavy Camel Corps (Guards and heavy cavalry detachments), the Light Camel Regiment (detachments mainly from hussar regiments), the Guards Camel Regiment (detachments from the Guards infantry regiments), and the Mounted Infantry Camel Regiment (detachments from the Egypt infantry troops). In addition, it would ultimately have the 1st Royal Sussex Regiment, a small Naval Brigade, three 7-pounder guns and the usual ancillary services. It was a tough march, sure enough, but Lieutenant Charles Townshend took some pleasure in the New Year celebrations.

‘At midnight - the last moment of the old year, 'Auld Lang Syne was sung from front to rear whilst on the march, the effect being very fine. The air was quite still, and the long column presented a weird appearance in the moon-light. At 1 a.m., we reached the wells of El Howeyiat. Here we halted and slept on the ground in our accoutrements. There was very little water in these wells, and that was muddy. Sentries had to be placed over the water skins. We halted at midday for the men's dinners. A ration of one pint of water to each man was served out, and there was a good deal of grumbling among the men. This was most irritating as the best means possible were taken by the officers, and the men seemed to have no idea as to the necessity of economising the water. That pint of water had to serve for everything until the next day, when we hoped to reach the Gakdul Wells. None of us had washed since leaving Korti, and one felt very dirty. I always managed to save a little tea in my pannikin for shaving purposes.'

Lieutenant Charles Townshend, Royal Marine Light Infantry

They reached Gakdul Wells, where there was a good and plentiful source of water, on 5 January. Here they were about half way to Metemmeh, but logistical confusion disabled any attempt to hurry onwards in their journey. Haste would surely have been advisable if they were to have any hope of coming down ‘like a wolf on the fold’ on a surprised Dervish garrison. But this could never be a 'dash' across the desert because the endemic shortage of camels meant that they would have to travel in awkward stages, tracing and retracing their steps in a crab-like motion.

The plan was to leave the Guards Camel Regiment to set up a base at Gakdul, while Stewart and the main force took the camels and returned all the way back to Korti to pick up more stores and allow the 1st Royal Sussex to ride the camels on the return of the column to Gakdul. Until the column returned, the Guards Camel Regiment was somewhat vulnerable if the Dervishes noticed they were there.

‘Outpost duty was rather severe, especially at night. Since we were by no means sure that the enemy might not be meditating a night attack on our cul-de-sac, we had to keep many sentries going. Two officers and some sixty-five men were on outpost duty every 24 hours. Since several high hills commanded all the tracks, ravines, and gullies by which we might be attacked, it was easy enough to post sentries during the day to see for many miles round. At night, however, it was different; a chain of sentries had to be established round the whole place, and with so many glens and gullies it was impossible to command the whole satisfactorily with a few men on a pitch-dark night. Oh, the agony of going the rounds four or five times a night! The whole distance on a map would not exceed three-quarters of a mile, if as much, but the fastest time on record was 48 minutes for the whole round. Uphill and downhill, over those sharp rocks, no path visible, as your lantern would be sure to go out at the first cropper, skinning your shins over every big stone, climbing down precipices you would never attempt by daylight, losing your way, your hat, your bearings.’

Lieutenant Lord Gleichen, Guards Camel Regiment

They knew the main column would not return for around ten days, but the Guards Camel Regiment made good use of the time, organising separate pools and troughs for men and camels, clearing a road and camp sites and building two redoubts on the heights above the gorge.

Stewart did not even set off from Korti until 8 January. With the second tranche was a small Naval Brigade of five officers and fifty-three men, which had been placed under the command of Captain Charles Beresford. It would be their role to assist in taking Gordon's steamers to Khartoum. Beresford had made sensible preparations that he struggled to explain to landlubbers.

‘The intervening days being occupied in preparations. An essential part of my own arrangements consisted in obtaining spare boilerplates, rivets, oakum, lubricating oil, and engineers' stores generally, as I foresaw that these would be needed for the steamers, which had already been knocking about the Nile in a hostile country for some three months. At first, Sir Redvers Buller refused to let me have either the stores or the camels upon which to carry them. He was most good-natured and sympathetic, but he did not immediately perceive the necessity. 'What do you want boilerplates for?' he said. Are you going to mend the camels with them? But he let me have what I wanted. With other stores, I took eight boilerplates, and a quantity of rivets. One of those plates, and a couple of dozen of those rivets, saved the column. The Gardner gun of the Naval Brigade was carried in pieces on four camels. Number One carried the barrels, Number Two training and elevating gear and wheels, Number Three the trail, Number Four, four boxes of hoppers. The limber was abolished for the sake of handiness. The gun was unloaded, mounted, feed-plate full, and ready to march in under 4 minutes. When marching with the gun, the men hauled it with drag-ropes, muzzle first, the trail being lifted and carried upon a light pole. Upon going into action, the trail was dropped and the gun was ready, all the confusion and delay caused by unlimbering in a crowded space being thus avoided.’

Captain Charles Beresford, Naval Brigade

The journeys to and from Korti were as rushed as possible, as Stewart was desperate to save time, but in doing so he further undermined the already inadequate camel resources of the Desert Column. The camels were not only often overloaded, but they also lacked rest, foraging opportunities, fodder and water. The consequences of this may not have been immediately obvious, but as they prepared for the next leg of their journey to Metemmeh, many of the camels were already suffering from exhaustion. Beresford did his best to reduce the damage suffered.

'The whole progress of the expedition depended upon camels as the sole means of transport. When a camel falls from exhaustion, it rolls over upon its side, and is unable to rise. But it is not going to die unless it stretches its head back; and it has still a store of latent energy; for a beast will seldom of its own accord go on to the last. It may sound cruel; but in that expedition it was a case of a man's life or a camel's suffering. When I came across a fallen camel, I had it hove upright with a gun-pole, loaded men upon it, and so got them over another 30 or 40 miles. I superintended the feeding of the camels myself. If a camel was exhausted, I treated it as I would treat a tired hunter, which, after a long day, refuses its food. I gave the exhausted camels food by handfuls, putting them upon a piece of cloth or canvas, instead of throwing the whole ration upon the ground at once.’

Captain Charles Beresford, Naval Brigade

To find out how they failed (Gordon ending up decapitated isn’t exactly a spoiler) and to find out how Major Kitchener returned to cement his fame a decade later, you can obtain a copy of Chain of Fire from all good bookshops in Britain as of today. Hart is no Kipling, and is certainly the farthest thing from David Starkey you’re ever likely to meet. You’ll find no jingoism here. This is a balanced, people-led narrative, vivid in imagery and comprehensive in recounting a piece of military history that might be more uncomfortable now than had he written this thirty years ago, but one that shouldn’t be airbrushed from our understanding of the nineteenth century.

I’d go so far as to say that Peter has yet to publish a book that wasn’t a gripping, if at times gruesome, narrative; basically he writes page turners, not always the case with military historians. Sad that I couldn’t be with you tonight but this book will be joining my library.

I've been trying to resist a Nile Expedition rabbit hole but it's CALLING ME 😱 gutted I can't make it to the launch event, hope all goes well!