FREE FEATURE: For Valour

My job as an historian seems pretty simple on the surface. I’m here to to paint you a picture of the past. There are different ways of doing history, all of them valid, but in a few weeks Nicolai Eberholst and I publish ‘Ring of Fire: A New Global History of the Outbreak of the First World War.’ (Info here) So for me, it is absolutely my job to write about multiple nationalities, multiple ethnicities, men, women, the elderly and children. Otherwise I’m sketching the outline of something and not properly colouring it in.

I don’t choose to include stories about all of these previously marginalised people alongside my standard fare of caucasian manhood bashing away at each other to be fashionable, or ‘woke.’ I do it because for a long time they’ve been left out of the story. Talking about new perspectives doesn’t mean you have to forget about the others. People aren’t thick, they can handle both. We’re just adding to the story, often including new perspectives, so that you, the reader, if you choose to, can imagine as complete a picture of the past as possible. Going back to my painter analogy, if I was going to paint a portrait of you and I left the red paint and the blue paint in the box because I couldn’t be bothered to use them, or it was too hard to blend all the colours together, or because I just didn’t like them, I wouldn’t be a good artist. But ultimately my reasons for making those decisions wouldn’t matter. More importantly, the painting I produced just wouldn’t be very good, and it certainly wouldn’t be an accurate likeness. It’s the same thing. I don’t consider myself ‘woke’, just professional.

And so, here are a selection of stories from several continents about ordinary people who were awarded gallantry medals for their extraordinary actions.

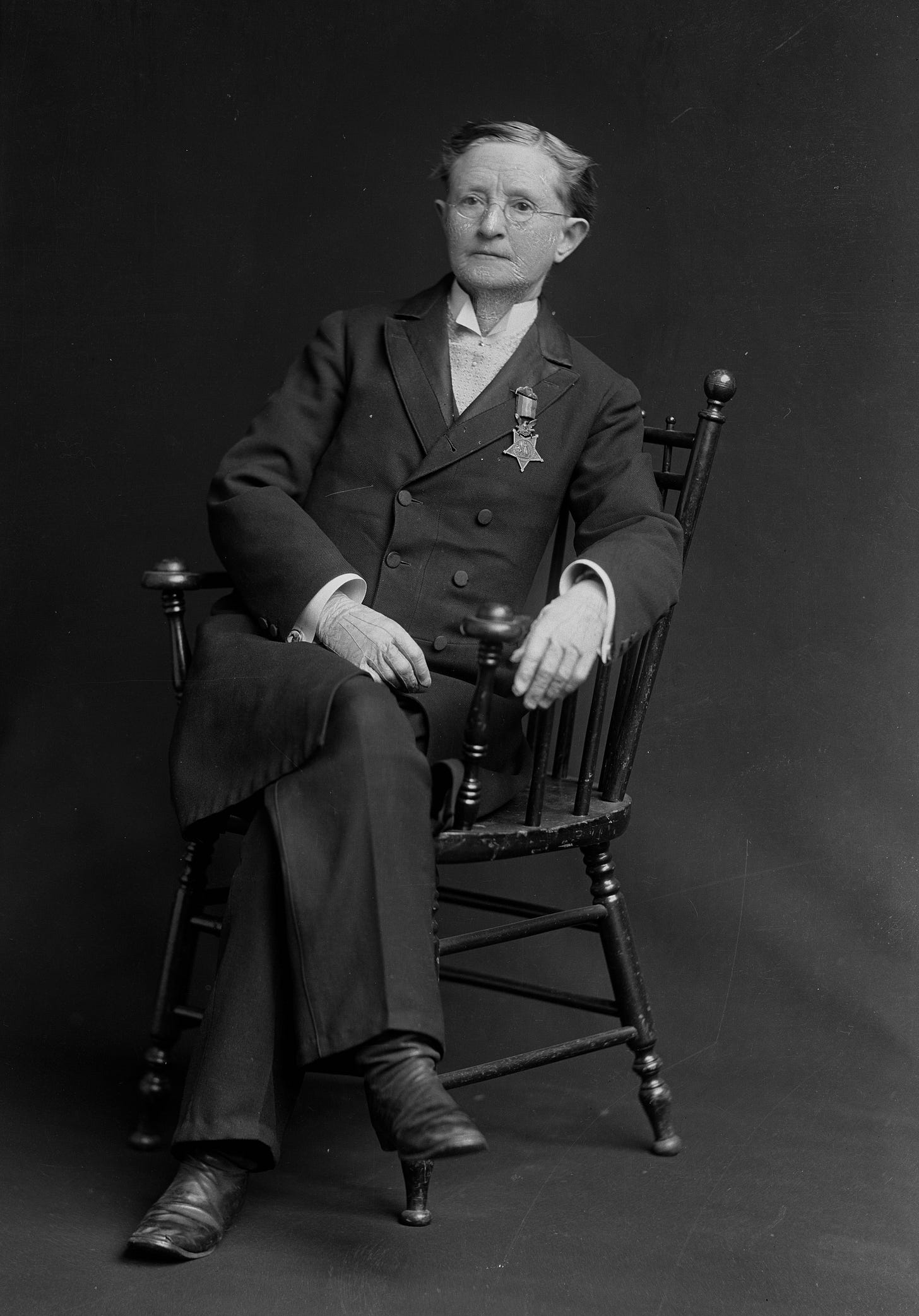

Mary Edwards Walker

(Wikipedia)

Kicking off with an absolute banger, Mary Walker was an abolitionist, suffragist, social reformer, surgeon, prisoner of war, and is the only female recipient of the Medal of Honour.

She attempted to join the Union Army immediately on the outbreak of the American Civil War, but was turned away despite her years of experience on account of being a woman. They asked her if she wanted to be a nurse instead. However, she did do this and eventually found her way to the front with the 52nd Ohio Infantry, becoming the first female surgeon to serve with, not in, the US Army. Again, no women allowed. She treated the wounded (unpaid) at the First Battle of Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and after Chickamauga. She also offered to work as a spy given her access to troops on both sides of the lines, and was again, turned down.

In April 1864, she was captured by Confederate troops immediately after having assisted one of their own doctors in performing an amputation. Accused of being a spy, she spent several months at Castle Thunder in Richmond, Virginia until she was exchanged for a Tennessee surgeon in August.

Among the many causes she championed, Mary could absolutely not be bothered with corsets and womenswear of the 1860s. In fact, she wore trousers as she treated the wounded because she said she needed to be able to move freely. She wasn’t into gender labels. She said: “I don't wear men's clothes, I wear my own clothes.” She referred to her style as ‘rational dress’ and criticised the impact of big skirts and piles of petticoats not only because they restricted movement but because she said they collected dirt. She experimented with shorter skirts over mens trousers, and eventually wore suits. She could often be seen sporting a top hat, and withstood no small amount of harassment for her choice of attire. She was assaulted in public, teased, and she did not care. She was even arrested in New Orleans in 1870, whereupon the police officer in question asked her if she had ever been in a relationship with a man. Actually she married another doctor, wearing a short skirt with trousers underneath, refusing to include "obey" in her vows, and insisting she keep her last name. She divorced him after he cheated.

(Wikipedia)

Mary tried to register to vote as early as 1871, but was turned away. As far as she was concerned, she already had the right, she just needed Congress to confirm it with legislation. This stance brought her into conflict with other campaigners who were asking to be granted the right to vote.

She died in 1919, at the age of 86, one year before the Nineteenth Amendment passed, guaranteeing women the right to vote. She was buried in a suit.

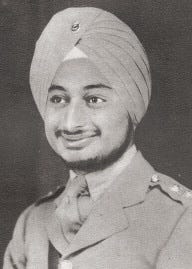

Karamjeet Singh Judge VC

Born in 1923, Karamjeet Singh was the son of a police chief in Kapurthala in the Punjab. With an brother serving in the Royal Indian Artillery, he opted to join the army instead of continuing his studies in Lahore, in modern Pakistan. Commissioned at Ambala, in 1945 he was 21 years old when he joined the 4th Battalion of the 15th Punjab regiment, who were preparing to take Rangoon.

(Wikipedia)

During the Battle of Meiktila, Singh took part in the action that would see him awarded the Victoria Cross:

In Burma, on 18th March, 1945, a Company of the 15th Punjab Regiment, in which Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge was a Platoon Commander, was ordered to capture the Cotton Mill area on the outskirts of Myingyan. In addition to numerous bunkers and stiff enemy resistance a total of almost 200 enemy shells fell around the tanks and infantry during the attack. The ground over which the operation took place was very broken and in parts was unsuitable for tanks. Except for the first two hours of this operation, Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge's platoon was leading in the attack, and up to the last moment Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge dominated the entire battlefield by his numerous and successive acts of superb gallantry.

Time and again the infantry were held up by heavy medium machine gun and small arms fire from bunkers not seen by the tanks. On every such occasion Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge, without hesitation and with a complete disregard for his own personal safety, coolly went forward through heavy fire to recall the tanks by means of the house telephone. Cover around the tanks was non-existent, but Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge remained completely regardless not only of the heavy small arms fire directed at him, but also of the extremely heavy shelling directed at the tanks. Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge succeeded in recalling the tanks to deal with bunkers which he personally indicated to the tanks, thus allowing the infantry to advance.

In every case Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge personally led the infantry in charges against the bunkers and was invariably first to arrive. In this way ten bunkers were eliminated by this brilliant and courageous officer. On one occasion, while he was going into the attack, two Japanese suddenly rushed at him from a small nullah with fixed bayonets. At a distance of only 10 yards he killed both.

About fifteen minutes before the battle finished, a last nest of three bunkers was located, which were very difficult for the tanks to approach. An enemy light machine gun was firing from one of them and holding up the advance of the infantry. Undaunted, Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge directed one tank to within 20 yards of the above bunker at great personal risk and then threw a smoke grenade as a means of indication. After some minutes of fire, Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge, using the house telephone again, asked the tank commander to cease fire while he went in with a few men to mop up. He then went forward and got within 10 yards of the bunker, when the enemy light machine gun opened fire again, mortally wounding Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge in the chest. By this time, however, the remaining men of the section were able to storm this strong point, and so complete a long and arduous task.

During the battle, Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge showed an example of cool and calculated bravery. In three previous and similar actions this young officer had already proved himself an outstanding leader of matchless courage. In this, his last action, Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge gave a superb example of inspiring leadership and outstanding courage.

Maria Boni Brighenti (thanks Vanda)

(combattentiereduci.it)

Born into a distinguished family in Rome in 1868, Maria Boni married an army officer by the name of Costantino Brighenti, and followed him to Libya when he was posted to the Royal Corps of Colonial Troops of Tripolitania as commander of the II Libyan Battalion. After waiting in Tripoli, she was allowed to join him in Tarhuna in April, 1915. Just a few weeks later, Tarhuna was besieged by rebels who cut the city off and prevented supplies and reinforcements from arriving.

During what happened next, Maria became the first woman awarded Italy’s Gold Medal for Military Valour, the country’s highest gallantry award.

Working as a nurse, she tended the wounded in a field hospital for about a month until, with a lack of ammunition, food and medical supplies, the commander of the garrison decided to try and retire on Tripoli. They moved out on the night of 17th June along the tracks of the Gebel, and a column made up of non-combatant civilians, including women and children, moved in the wake of the soldiers. Having reached the Ras Msid valley, the Italian formation was surrounded and attacked by the rebels, and a massacre ensued.

Wounded by a ricochet shot while assisting her patients, Maria refused to leave her post, and was killed in the frenzy. Her husband was taken prisoner and, after a year in captivity, committed suicide on 16 May 1916. Maria’s body was body was later found and identified by the lace on her dress. Her citation reads:

During the long blockade of Tarhuna, she was an example of military virtue; with a very lofty and strong spirit she lavished her care on the wounded and dying, comforting them with the infinite resources of her sweet femininity. On June 18, 1915, following the garrison that was retreating towards Tripoli, she resolutely refused to save herself, wanting to follow the fate of the troops; struck several times by enemy bullets while she was helping the wounded and encouraging the fight, she died heroically among the fighters.

Maria and her husband were both eventually laid to rest in Bari.

Yesaku Kubodera & Alexander Wuttunee Decoteau

Lastly, here is a story I have never forgotten, of a multi-ethnic Canadian unit in the miserable, dying stages of the Third Battle of Ypres in 1917. It might be a humble Military Medal in this case, but it’s a story worth telling. By 30th October, the Canadians were within spitting distance of Passchendaele itself, and ready to try again.

Alex Decoteau was a Cree Canadian. Born in 1887 on the Red Pheasant Indian Reserve near North Battleford in Saskatchewan, having worked as a farm hand he moved to Edmonton and by 1909 had become the first indigenous Canadian police officer in the city. Promoted to Sergeant by 1914, Alex was a prolific runner, dominating the middle and long distance circuit in Western Canada. He had even competed in Stockholm at the 1912 Olympics, eventually finishing sixth in the 5000m after suffering with cramp during the race. Enlisting in April 1916, Alex joined his local battalion, the 49th, and on 23rd October, he and his compatriots were met by guides at Ypres and led up towards the front lines to begin taking in supplies for their projected attack. Though guns were already in place, as the attacks of the 26th had moved forward such a limited distance, there was an immense amount of work to be done before zero hour, namely the bringing up of enough ammunition, supplies and stores across the morass to equip another advance. There was no chance of the battalion conserving their energy before they went into action. As of 25 October large working parties reported for duty to work on laying tracks composed of bath mats leading up to the forward most position. Another spent a day carrying ammunition forward to form dumps ready for battle. All the while enemy aircraft were active in bombing Alex and his comrades as they went about their work.

Alex and the rest of his battalion were destined to go from being workmen to leading an attack without a break. On 28 October the 49th Battalion relieved another Canadian unit in support; 22 officers and 560 men going into the lines. The plan for 30th would see them facing stiff German opposition, with the stronghold at Meetcheele the formidable obstacle in their path as they attempted to advance towards Passchendaele. Some of the finer details of the plan were not received until the afternoon of 29th, but there could be no delay. Alex and the rest of his battalion moved off into the sticky morass that led up to their assembly positions. Laden with overcoats which would be left at their jumping off point, rubber sheets, 170 rounds of ammunition, sandbags, white flares to signal aircraft with their positions, haversacks stuffed with iron rations, tommy cookers, water bottles, solidified alcohol, the men would have struggled in ordinary conditions with their loads. As it was, the route was all but impassable. To make matters even worse, as Alex made his way along sodden tracks, the enemy began to lay a heavy barrage on the 49th.

To leave the wounded in the slime would have condemned them to death, yet every minute of delay meant more casualties. Battalions began to bunch along the route, exposing yet more men to intense artillery fire before the battle had even begun. Thinking quickly, the commanding officer of the 49th decided that the new arrivals should overtake them, slowed as they were by wounded men. “In the finest spirit of inter-regiment chivalry [he] gave orders that very wounded man of his unit was at once to be lifted off the duck-boards and supported in the mud by two of his comrades until [they] were safely past.” Somehow, the men managed to reach the line of tape pulled across their starting position. There was nothing left for Alex Decoteau to do but wait. The moon was out and there seemed to be little hope that the enemy had not been observing their every move as they arranged them- selves. “The long hours of waiting before the assault will never be forgotten by those who shared them. As the darkness fell the evening shoot died away and the flickering flames from the guns... were extinguished.”

Shortly before 5:50 am the protective barrage crashed down. “Once more the... front was one flaming stretch of flashing guns and bursting shells.” But to the alarm of all about to advance, almost immediately the enemy responded, as if he had been readily waiting by his guns. The lines along which the Canadians were assembled came under immediate, heavy shellfire. Almost straight away, the 49th’s machine-gunners were put out of action, some of their own shells added to their plight by falling short. Nonetheless, “scrambling over the hastily constructed trenches that marked their advanced lines, the Canadians resumed their offensive against the outlying defences of Passchendaele.”

Under a bombardment that seemed light, the likes of Alex Decoteau struggled into the face of all that the enemy could throw at them in an attempt to defend their positions. On the right, one company was almost annihilated before it could get into its stride. It was noted up and down the line that the rate of rifle and machine-gun fire being levelled at the advancing Canadians was extraordinarily high. Any initial progress was being made by short desperate rushes, but their left flank was in the air and as numbers waned disciplined fighting grew harder and harder to sustain. It was clear that no further advance was possible. Ruses were apparently used by the enemy to further deplete Canadian numbers. Their heads swathed in bandages, “a party of presumably wounded men made signals for assistance and afterwards opened fire from the position occupied.”

By 7 am, one officer estimated that there were in the region of 125 men still left in action. As the day wore on and the survivors attempted to consolidate their sketchy positions, German artillery shells continued to pound the area occupied by Alex Decoteau and his compatriots. Enemy snipers lurked in pits with their rifles, attempting to pick of the depleted battalion one by one. Before the morning was over one of them had struck and killed Alexander Decoteau. Originally buried some 1500 yards west of Passchendaele with four of his countrymen in an unmarked grave, as the area was clear after the war, his body was exhumed. Alex was identified by his name disc and finally laid to rest at Passchendaele New British Cemetery, plot XI.A.28, in March 1920. Since a proper Cree burial did not occur, his relatives and friends performed a special ceremony in 1985 that brought his spirit home to Edmonton.

Following the death of Alex Decoteau, both a park and a housing development were named in his honour and he was a lauded as a war hero. A very different fate awaited another immigrant serving in the 49th Battalion.

Yesaku Kubodera had been born in Yamanashi Ken, to the southeast of Tokyo and in the shadow of Mount Fuji. In 1907 he sailed via Honolulu with a number of other emigrants and arrived in British Columbia. Lying about his age by a few years, Yesaku, diminutive and in his mid-thirties, had become a Canadian citizen and was working a labourer when he enlisted at Swift Current.

The first Japanese immigrant arrived in Canada in 1877. Since then, thousands more had set sail largely to take up work on farms, as fishermen, miners and loggers. The largest concentrations remained in British Columbia and on the West coast and in 1906 the first Japanese language school opened in Vancouver. The local population did not always welcome the Japanese. in 1907 a group of white supremacists did much damage to Japanese and Chinese buildings in the city, to which Vancouver’s Asian workers immediately responded by calling a general strike. There was more than one reason driving Japanese-Canadians to fight. Britain was Japan’s ally in the Great War. Enlisting to fight not only supported their adopted home of Canada, but their homeland and their British allies too. Enthusiastic plans to raise a battalion of their own to fight in Europe did not come to fruition. Japanese-Canadians did not even have the right to vote, and men who joined the Canadian Japanese Volunteer Corps in the hope of doing their bit were ridiculed on occasion, and certainly not taken seriously by the military authorities, which even led to rioting. The recruits were determined, however, to see active service and in the case of many, they travelled to Alberta where they found recruiters more willing to accept their services. Yesaku Kubodera had enlisted in 1915, and sailed for Europe on the SS Caronia the following year. He had joined the 49th Battalion on the Western Front in March 1917. On 30 October, Yesaku Kubodera had found himself stuck fast in the swamp-like conditions in front of Passchendaele. However much he tried, he could not free himself, and there was nothing he could do but wait for help.

Until 11 am, the weather was fine, but it was a cold morning, and as he flailed in the mud, a biting wind whipped around Yesaku’s face. Then it began to rain. The rest of the battalion continued to attempt to consolidate their positions, until at 1 pm orders arrived to the effect that the tattered remnants of the battalion was to pull itself together and try and attack again in an attempt to seize their final objective. Given the state of the troops, this was clearly impossible and the order was rescinded, to the compounded relief of those still in action.

In the meantime, after three hours of being stranded in clinging mud, shells and bullets swirling in a tempest about him as he remained helpless, Yesaku Kubodera was finally dug out of his predicament. On his feet, he refused point blank to make his way to a dressing station, determined to fight on. Throughout the course of the afternoon, the 49th Battalion would face nearly half a dozen counter-attacks launched at them from north of Passchendaele. Yesaku did not falter. Determined, showing remarkable aggression, he ignored the heavy machine-gun and rifle fire being levelled at the surviving members of the 49th, and blazed away with his rifle “showing a splendid example to all ranks of fortitude and devotion to duty.” For his actions on 30 October, he was awarded the Military Medal. At nightfall, the incessant shelling finally stopped and the line was reinforced. Nearly 600 men had gone into action with the 49th Battalion. More than 75% of them would become casualties on 30 October 1917, the worst day the battalion suffered in two world wars.

Japanese volunteers in Canada (Nikkei Museum, Vancouver)

Yesaku Kubodera would survive the war. Suffering from influenza when peace came in November 1918, he spent his last months in the army acting as an officer’s servant. He embarked at Tilbury in September 1919 and on reaching Canadian soil was discharged. Following the war, he settled as a farmer to the southeast of Vancouver, married, and he and his wife Chikayi had at least one daughter. In 1920 Japanese- Canadian soldiers were honoured with a cenotaph that was unveiled in Stanley Park on the third anniversary of the fighting at Vimy Ridge. Speaking on the survivors’ behalf, one of their number declared: “we don’t forget what we owe to Canada and we were proud to fight when Britain declared war on the common enemy.”

On 7 December 1941, Japan launched an attack on Pearl Harbour. More than 23,000 people of Japanese origin were living in Canada, more than three quarters of whom were Canadian citizens. This counted for little when concerns began to gain momentum about spies and sabotage. Neither the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, nor the military raised concerns about the proximity of people of Japanese extraction on the west coast, but the Government took a different view. “Persons of Japanese racial origin” were to be removed from a 100 mile “restricted zone” in British Columbia, away from the coast. Yesaku Kubodera had by this time lived in this zone for a quarter of a century. No service in the Great War was taken into account, and instead, the Canadian Government embarked upon a policy of “ forced dispersal, mass internment, and dispossession” of Japanese-Canadians in 1942.

Now retired and in his sixties, Yesaku was one of nearly 22,000 people affected. Half of those had been born in Canada. “Men, women, and children were forced to leave their homes, many with only two days’ notice or less to prepare. With severe restrictions on luggage, they left behind not only significant assets such as homes, cars, and boats, but also treasured heirlooms and many other precious possessions. These were later sold by the Government without the owners’ consent. The largest number of Japanese-Canadians were sent to hastily built camps in the British Columbian interior, where they lived in tiny, crowded shacks with no insulation... Men aged 18 to 45 were forced to leave their families to work in road camps, or, if they protested against this, were sent to prisoner of war camps. Some families, in order to stay together, went to sugar beet farms on the prairies, where they worked very long hours and lived in poor conditions for almost no pay, or went to other provinces.” 965 Japanese-Canadians were sent to inland to Kaslo, Yesaku and his wife Chikayi among them. Within six months he had fallen ill and on 19 November 1942, almost 25 years to the day after his acts of bravery in front of Passchendaele, Yesaku Kubodera died interned as an enemy of Canada. At that point he had lived in Canada for nearly forty years. Chikayi died on Christmas Eve, 1943, in the same camp. After her father’s death, their daughter was denied the right claim to her inheritance.

Following the surrender of Japan in 1945, Japanese-Canadians were still forbidden from returning to the West Coast. Instead they were given a choice of relocating east of the Rockies or moving to Japan. In 1949 the Government finally allowed people of Japanese origin to move freely within Canada and reinstated their right to vote. In 1988 the Canadian Government formally acknowledged the country’s mistreat- ment of Japanese-Canadians during and after the Second World War and granted compensation to survivors.

Japanese-Canadian soldiers fought on the Somme, at Vimy Ridge, Passchendaele and up and down the Western Front during the Great War. 55 men of the original Canadian Japanese Volunteer Corps did not return home. Thirteen men, including Yesaku Kubodera, were awarded gallantry medals. A Roll of Honour had been produced in the aftermath of the war. When forced to leave British Columbia in 1942, one old soldier, a member of the Canadian Legion, took the Roll with him. He kept it safe for 25 years until the centenary of the arrival of the first Japanese immigrant was celebrated in Vancouver in 1977, when he brought it home. “A descendant of samurai... Corporal Kubota considered returning the Roll of Honour to be his final obligation to his comrades.” He died in 1978. Before doing so, he penned a poem for those who fell. Translated from Japanese, it reads:

Although you are gone, you are not dead,

Surely the setting sun will rise again for you

Your heroic spirit will live in our hearts,

We take the torch from your hand to fight and carry on

Fantastic piece 👏🏻

A quite marvelous introduction to an astonishing example of heroic deeds by mere mortals. Both of which we could certainly use more of. Thank you, Alex (not woke just professional)