In 1983 Kenneth Rose, a biographer of King George V, wrote that: “the British Government would willingly have offered [the Russian Imperial Family] asylum but for the fears expressed by Buckingham Palace; and at the most critical moment in their fortunes they were deserted not by a radical Prime Minister seeking to appease his supporters, but by their ever affectionate Cousin Georgie.”

Wrong, and wrong. I found out that the late Queen was so unhappy with Rose over this that until 2015, when I happened to send a letter asking to look at George V’s papers, she hadn’t let anyone else write another biography since. So this one is for Her Majesty. Buckle up, because the accusation that heartless Cousin Georgie conspired to wrong his cousin and then left his relatives to burn without a second thought is not only unfair, but insulting given everything that followed.

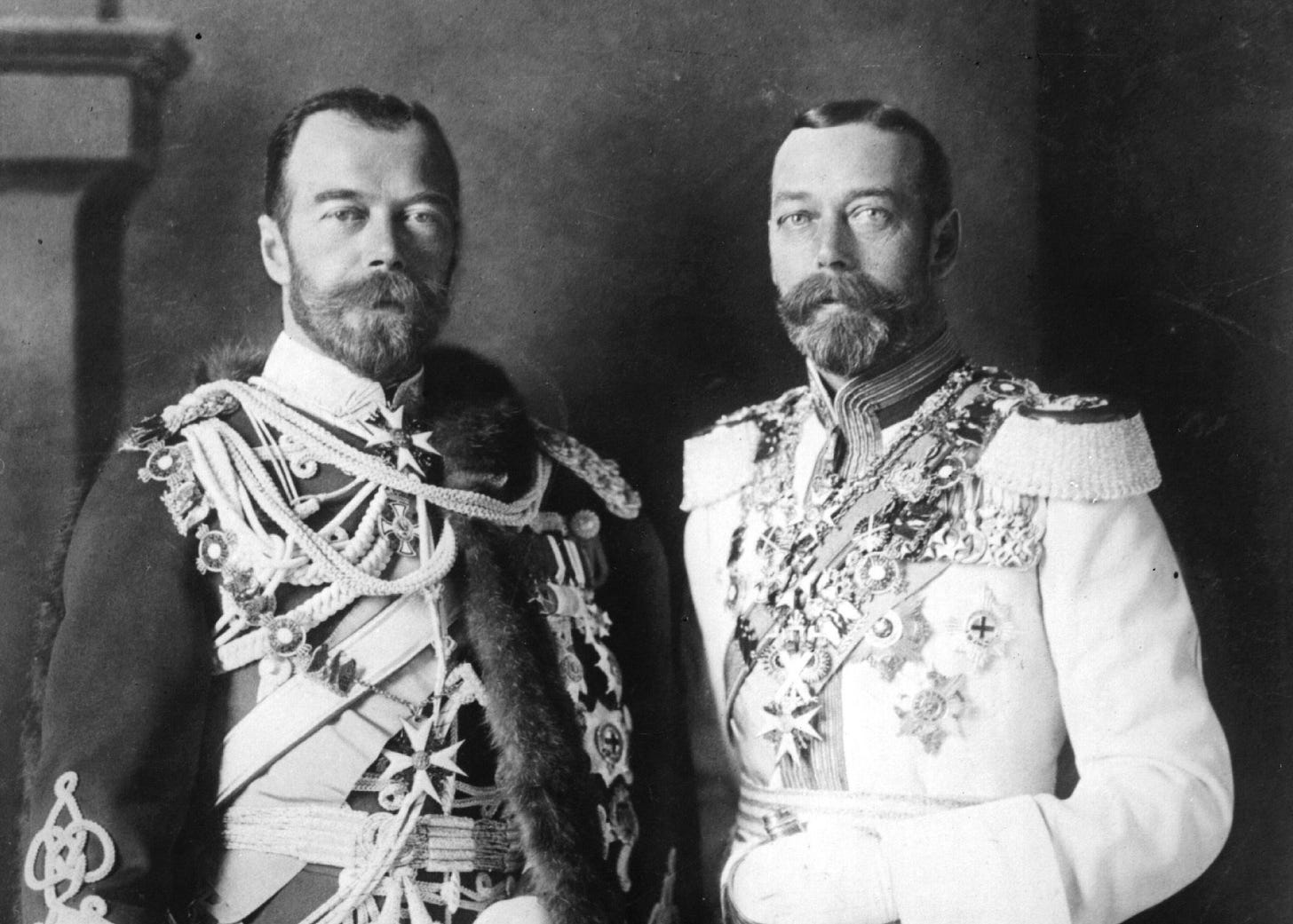

Nicholas (left) and ‘Cousin Georgie’ pictured together.

“Slow Drops of Poison”

Nicholas II was the wrong man, in the wrong place, at the wrong time. Had fate called upon him to reign as a constitutional monarch in the same vein as George V, he might have done well. But fate put him somewhere else. Instead, he succeeded his father in 1894 and found himself at the head of an autocracy moving into its death throes. Said father was a fierce, bull of a man. He once ripped the roof off of a train carriage to rescue his children from a wreck; and tied a piece of cutlery into a knot and threw it at an Austrian representative making veiled threats. Nicholas was the polar opposite. He was a decent man, he loved his country, and he wanted the best for his people, but he inspired fear in no-one. He could not even sack someone face to face. He’d send them a note. If you were recruiting an autocrat, he wouldn’t even make it to an interview.

By 1914, Nicholas’s power had been eroded, but the war had a galvanising effect on Russia. The Tsar was a figure they could rally behind against a common enemy. The same could not be said of the Tsarina. Alix of Hesse was Queen Victoria’s granddaughter. Her first visits to Russia saw her labelled as clumsy, awkward, and badly dressed; which was unfortunate but not critical. Following her marriage to the Tsarevich, everything she said and did continued to scream awkwardness. Her determination to help and support her beloved husband in his burdens as Tsar made the country believe that she influenced all he did. By the time the war began, the Empress Alexandra was viewed as a physical barrier between the people and their ‘little father;’ as dragging down the monarchy. Her country of birth was weaponised against her. “The picture representing her as being pro-German is an entirely false one,” wrote one acquaintance years later. “Her one idea was to preserve the autocracy.”

Added to all of that was the unfortunate knock-on effect of Alix’s struggle to produce an heir. In 1904 she finally gave birth to a son, Alexei and secured the succession. By onset of the First Word War, however, for more than ten years, the Empress had carried the weight of not only her son’s haemophilia, but also trying to keep it a secret from the world. She believed that she was helped through all of this by Grigori Rasputin, a perennially unwashed, semi-literate Siberian monk, who nonetheless was shrewd enough to have claimed a place in the inner sanctum of the Imperial Family and convinced the Empress that he had the power to alleviate her son’s suffering. General Hanbury-Williams, the British representative at Russian Headquarters, thought he was “an unscrupulous blackguard, posing as a saint,” who preyed on the vulnerable Empress, “whose love for her son and naturally nervous temperament made her an easy prey.” All sorts of sordid rumours about the Mad Monk and the Empress circulated throughout Russia. This unconventional advisor and his exalted position spelled trouble for Nicholas in the eyes of his people, especially “for all those intriguers and place-seekers who had their own axes to grind.” Hanbury-Williams called his influence on the autocracy “slow drops of poison,” which would ruin Russia.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Alex Churchill’s HistoryStack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.