Coming up:

As you read this, the Great War Group’s annual conference will be in full swing in Leicester, but over the next few weeks I’m going to be putting a spotlight on some of the trips I’m running next year.

First up, in June Kate Jamieson and I are going to be taking a group to Orkney for five days of military and naval history, with an essential trip to the unique, prehistoric site at Skara Brae thrown in too. We’ll be walking in some of the very last footsteps of Lord Kitchener, exploring the Churchill Barriers, looking at optical illusions created by Italian pows, paying tribute to the men of HMS Royal Oak and lots more. For full details of dates and prices click on the image below:

This Week:

On Monday, I shared some content from a find in an antiques market in Salisbury…

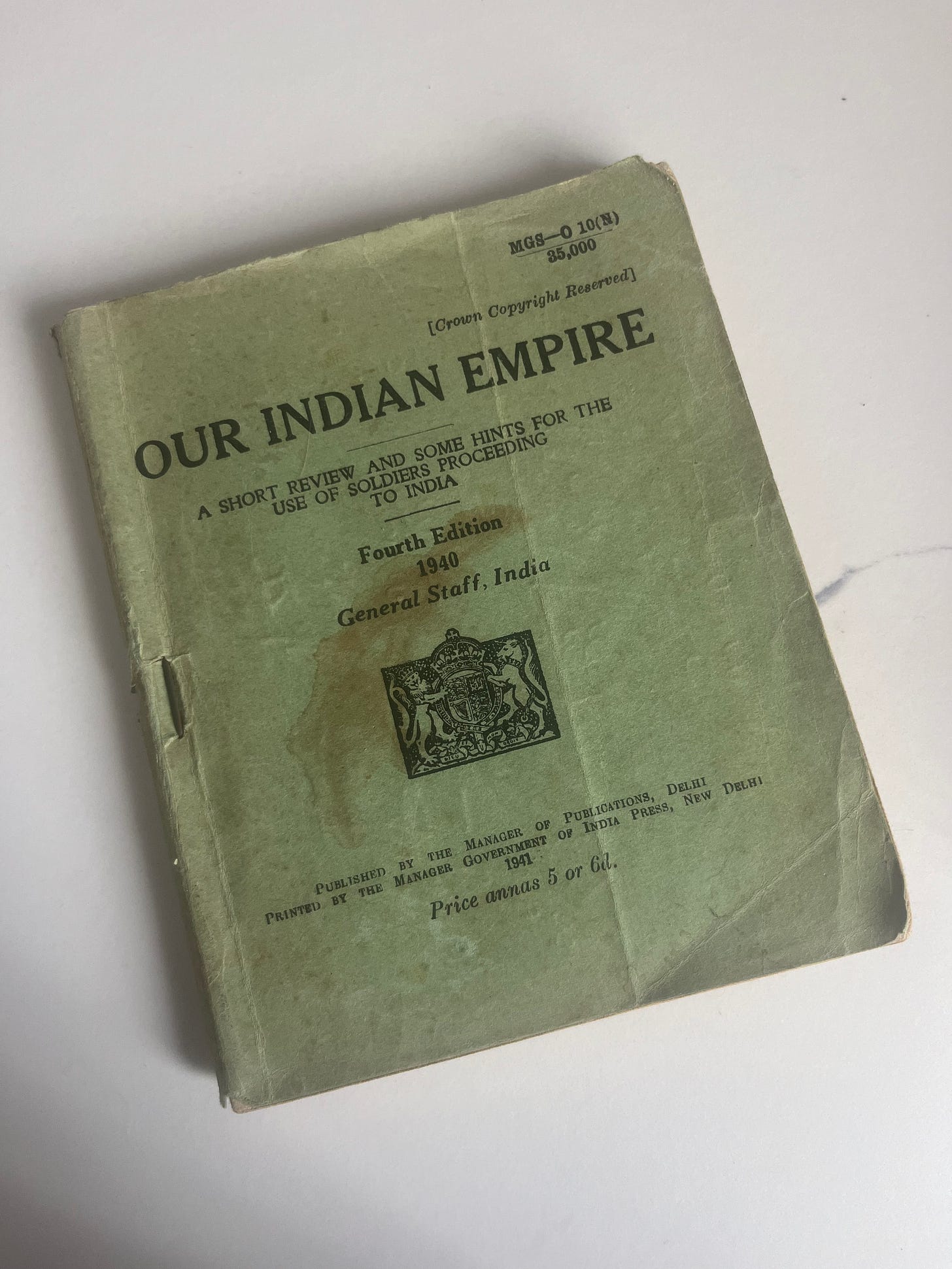

Ferreting about in an antiques market last week I came across a little green booklet. Turns out that it was a guide for British soldiers posted to India and it was dated 1940, just a few years before partition. Grabbed it, obviously, because what better rabbit hole for a Monday morning than the party line rolled out to servicemen in the middle of a war? How did the Government view India, her people, and it’s impact on the subcontinent up to that point?

First thing, there was a price on the front, which means perhaps this wasn’t issued to everyone, and it was merely available for those who wanted to part with a sixpence in order to own one. Second, what was the point? That, was covered in the opening chapter, which provided an overview of ‘Our’ Indian Empire:

‘Everyone going abroad will find it a great advantage to learn beforehand something about the people likely to be met in the new land; the climate there, and the best way to adapt oneself to the new surroundings. The soldier should also try and appreciate at his true value the fighting man of the country. This is of especial importance in India, where Britons and Indians are liable to fight side by side.’

The booklet goes on to give a lengthy introduction to ‘India’, which at the time also comprised other modern-day countries such as Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh etc.

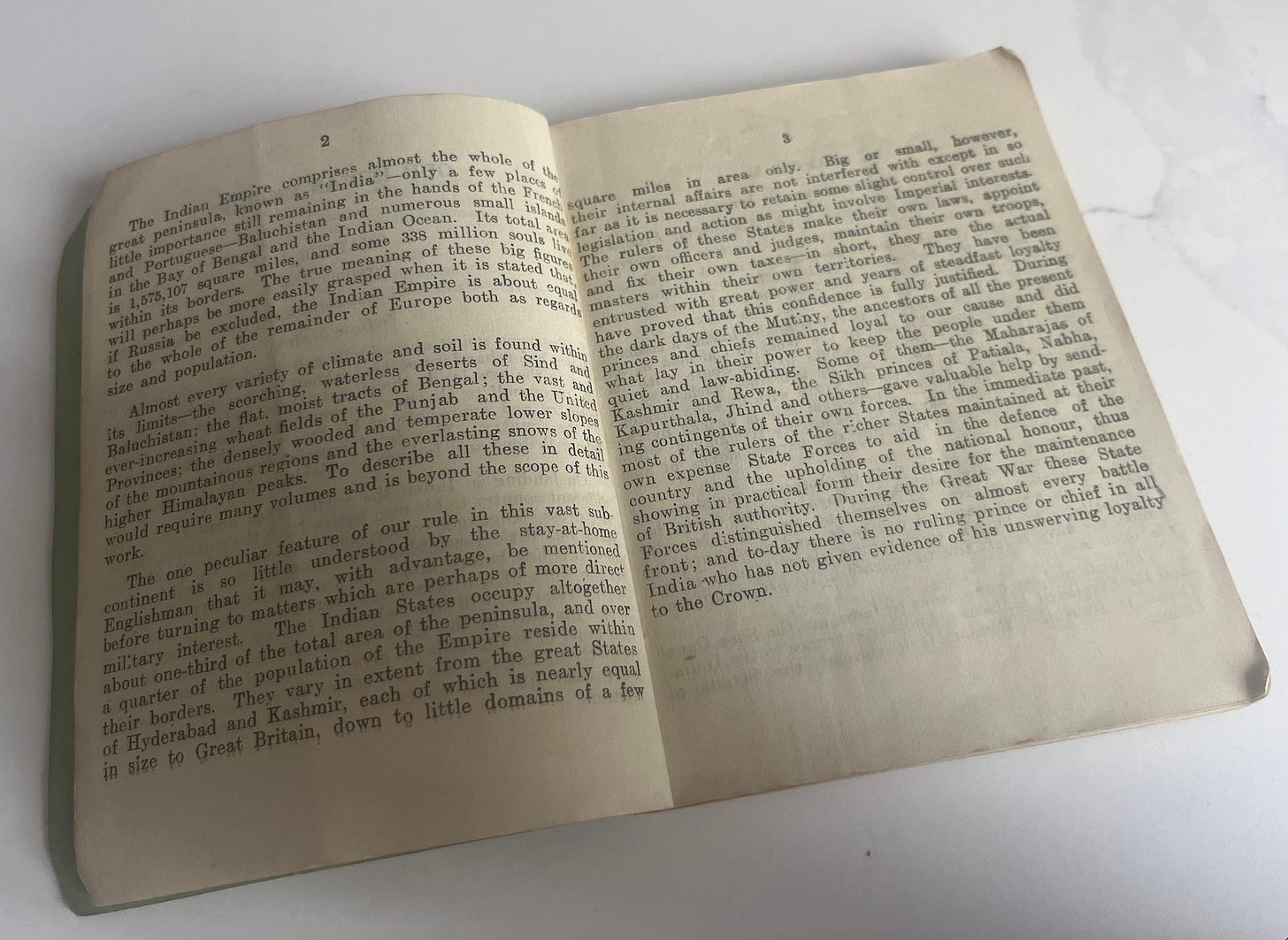

One thing that as really useful about it, was the explanation about distinctions within India about what was controlled by the British, and what technically wasn’t. If you thought we controlled the whole lot, you’d be wrong. This is pretty crucial for understanding the different responses throughout India on the outbreak of either war. Yes, there was an Indian Army, and yes, India was a part of the British Empire, but parts of the country were also under the control of various princes. This is how the booklet lays it out:

‘The one peculiar feature of our rule in this vast subcontinent is so little understood by the stay-at-home Englishman that it may, with advantage, be mentioned before turning to matters which are perhaps of more direct military interest. The Indian states occupy altogether about one-third of the total area of the peninsula, and over a quarter of the population of the Empire reside within their borders. They vary in extent from the great States of Hyderabad and Kashmir, each of which is nearly equal in size to Great Britain, down to little domains of a few square miles in area only. Big or small, however, their internal affairs are not interfered with except in so far as it is necessary to retain some slight control over legislation and action as might involve imperial interests.

The rulers of these states make their own laws, appoint their own officers and judges, maintain their own troops and fix their own taxes - in short they are the actual masters within their own territories.’

Here’s how they managed to wield this power. And yes, some of this is about to be uncomfortable reading from our seats in the 21st Century…

‘They have been entrusted with great power and years of steadfast loyalty have proved that this confidence is fully justified. During the dark days of the Mutiny, the ancestors of all the present princes and chiefs remained loyal to our cause and did what lay in their power to keep the people under them quiet and law-abiding. Some of them… gave valuable help by sending contingents of their own forces. In the immediate past, most of the rulers of the richer states maintained at their own expense state forces to aid in the defence of the country and the upholding of national honour thus showing in practical form their desire for the maintenance of British authority. During the Great War these state forces distinguished themselves on almost every battle front; and today there is no ruling prince of chief in all India who has not given evidence of his unswerving loyalty to the Crown.’

Yep. This is starting to feel grubby already. Here’s the 1940 interpretation of the Indian Mutiny, aimed at modern day soldiers being sent to India…

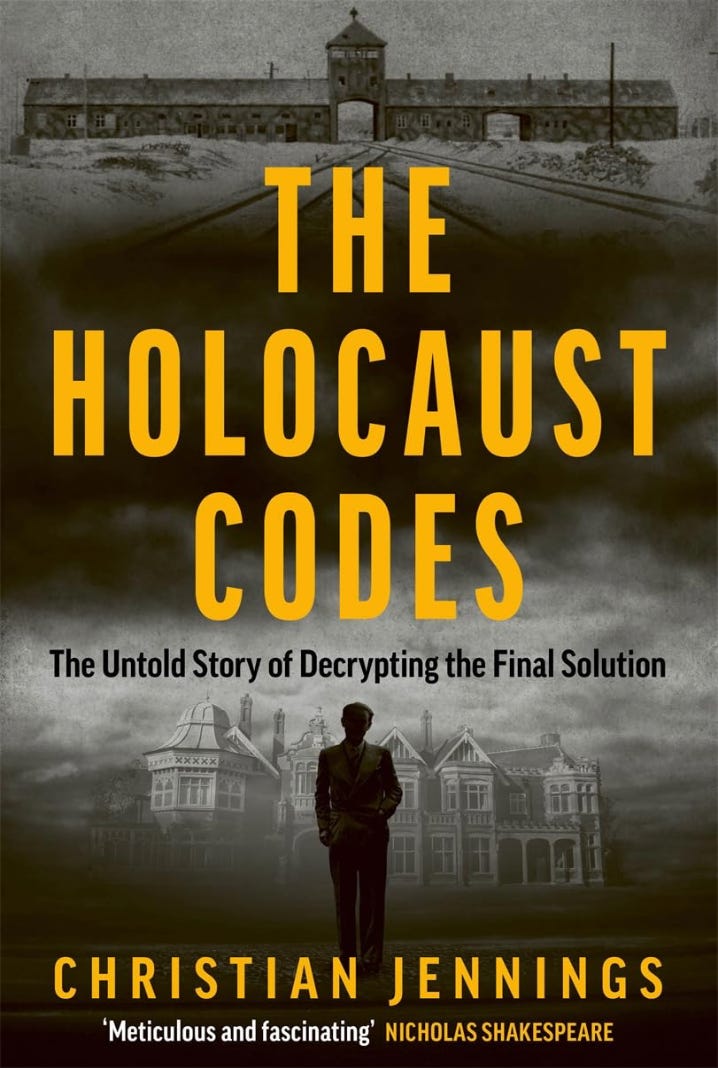

Then on Thursday I gave you another free book preview, this time on the latest offering from my friend Christian Jennings…

If you’ve read anything else by Christian Jennings, who ranks as one of the loveliest people to appear on History Hack, you’ll know that he’s adept at finding a niche thread that’s part of a well-known story, and then yanking on it. Hard.

His latest is no different: The Holocaust Codes: The Untold Story of Decrypting the Final Solution, starts like this:

‘On the morning of 4 April 1944, a twin-engined De Havilland Mosquito from 60 Squadron, South African Air Force, took off on a reconnaissance mission from San Severo, near Foggia in south-eastern Italy. To save weight, the aircraft carried no machine-guns, cannon or bombs, but only two long-focal-length cameras, one mounted under each wing. The South African crew - pilot Lieutenant Charles Barry DFC and navigator Lieutenant Ian McIntyre - were tasked with photographing the huge I. G. Farbenindustrie AG synthetic oil and rubber plant at Monowitz in southern Poland in preparation for a possible bombing raid. The return flight took five hours, and at a height of 26,000 feet, they were over the target for four minutes.

That day, one of the two cameras was malfunctioning, so, to be sure they obtained adequate images, the crew made two passes, from west to east and back again. On the second pass McIntyre left the cameras running slightly longer than usual to guarantee good coverage. Then the South Africans spotted enemy aircraft, and the unarmed Mosquito turned for home.

When the film of the second pass was developed back in Italy, the final frames were found to show a large site containing small buildings laid out in rows. Little attention was paid at the time to these: the target, after all, was the IG Farben plant five miles away.

It was only in 1979, some thirty-five years later, that photo-analysts from America's Central Intelligence Agency recognised them for what they were: the first Allied aerial shots of Auschwitz.

Eighty years after the two South Africans flew that sortie in their unarmed Mosquito, it seems inconceivable that back then the world had not heard of Auschwitz, that the grisly images of rows of barrack blocks, the crematoria, the wire, the railway lines, now so imprinted on human consciousness, could then have been nothing but an anonymous image from the skies. One whose identity would only be recognised and admitted to in 1979. Yet that is how the Holocaust occurred, that is how its physical institutions were concealed, how its perpetrators murdered millions of people, precisely because it was anonymous, it was hidden and as much as possible of the documentation and evidence was covered up.

However, although the camp complex at Auschwitz-Birkenau may have been unrecognisable from a high-flying reconnaissance aircraft, by April 1944 its existence, and the existence of other extermination and concentration camps and programmes of mass execution, was the subject of a flood of reports and rumours from inside occupied Europe. Some of the precise details, however, had for some time been known to a select handful of Allied intelligence and government officials in London and Washington. One of the primary ways they had discovered what the Germans were doing was through cryptanalysis, the decryption of encoded SS and German Police and intelligence signals that gradually revealed how the Third Reich was murdering six million people. That cryptanalysis, that decryption, those signals and that discovery of a state-sponsored programme of mass murder is what this book is all about.’

Christian’s own experiences as a journalist have shown him some of the very worst of humanity. In fifteen years as a foreign correspondent, he witnessed genocides and ethnic conflicts across twenty-three countries, including Rwanda, Bosnia, Kosovo and Democratic Congo. ’Out on the red dirt tracks of central Africa's Great Lakes Region,’ he explains:

‘in the sleety fog of frozen Balkans mornings, and across trails of mass graves and execution sites, I watched and learnt and reported on how genocide and mass atrocities happen. I wrote books on war crimes and international justice in these countries, as well as on the work of the International Commission on Missing Persons, which has revolutionised the science of DNA-assisted identification, helping to identify some of the thousands of people who go missing following conflicts in such areas as the western Balkans, Iraq, Syria and Ukraine.’

The author is based in Italy, and some of his previous history writing reflects this. He has written Second World War books about both Italy and the Holocaust. The last time I interviewed him, it was about The Third Reich is Listening, where he gave a detailed account of German codebreaking, ‘attempting to counteract the popular assumption of uncontested Allied superiority in this field.’ This latest book is not subject matter for a faint-hearted historian to tackle, but on paper, it looks as if Christian’s entire career has been building to this book. He certainly feels that way. ’It was as though all the different yet inter-connected topics of the past thirty years,’ he writes:

‘have led towards this current subject. The path has unwittingly progressed from the corpse-strewn interiors of Rwandan churches in 1994, to the machetes, burning villages and Kalashnikov tracer of civil war and ethnic cleansing in the eucalyptus forests and villages of Burundi - ironically, like Rwanda, one of the world's most beautiful countries. It has gone from the torched interior of a Kosovo coffee bar in 1999, the flame-blackened room strewn with the brass glimmer of cartridge cases, where Albanians were murdered by Serb paramilitaries, to the exhumed mass graves, the mortuaries and DNA laboratories of Bosnia, and to international courts in The Hague. At every step, the questions How?' and Why?' and What happened?' seemed to beg for answers. Investigating genocide, knowing something of how wartime codebreaking had worked, and where the perpetrators had left their traces across twenty countries, has enabled me to look into the overarching drama behind one of the most extraordinary stories of all.’

Which brings us to the two men pitted against each other in this book. The first is Nigel De Grey, ‘one of Britain's foremost codebreakers in the First World War.’ Eton educated, he nonetheless failed the entrance exam for the Foreign Office, and instead went into publishing. On a meandering path into naval intelligence, his watershed moment in the last war involved the Zimmerman telegram…

Next Week:

Come back to see an Arab-view of the Crusades, and for some RAF content from WW2…

Your writing is so easy to follow and stay in tuned with. I find myself a little behind in your stories as I get ready for my annual return to Belgium where I first met you and Beth. A connection I hope never gets broken. Thank you Alex.