FULL FEATURE: WW2 Service of a Queen Pt.I

RMS Queen Mary sails to war...

So this started off as a short piece about why the Queen Mary was awesome. Then it turned into an article about her wartime service, and then I lost my mind and went off and listened to about 200 interviews and it became what will need to be a two part feature about all the ways this special ship touched the lives of men and women in the years 1939-1945. Lots of them adored her, and dined out for decades on having sailed on her. Others remembered being crammed into her by the thousand with less affection, and for a few, she represented the worst day of their lives, or even the end of it…

This is apparently how she came about: Picture a stuffy boardroom on the fifth floor in the Cunard building, overlooking the Mersey in 1926:

“Well, how long was the Mauretania?”

“790 feet.”

“The Aquitania?”

“901 feet.”

“Well, let's make this one a thousand feet and see what happens.”

The Queen Mary was a comeback for British shipping giants, and though that flippant conversation made it all sound very easy, in actual fact, it would be years before she was built, fitted out and ready to sail.

First off, forget Titanic. Forget that image of hordes of immigrants stampeding westward and churning huge revenues for shipping companies, and requiring a ‘stack ‘em high’ philosophy below decks. The North Atlantic trade looked nothing like that by the time the world emerged from the First World War and ploughed towards the 1930s. Thanks largely to a quota system for immigration that came in in 1923, numbers of a million odd emigrants a year prior to 1914 had dropped to about 90,000 heading to America by 1931. This amounted to a seven million pound loss in revenue for the likes of Cunard and White Star.

The double keel of 534 laid out at John Brown’s (All photos come from the book I talk about in my sources at the end, unless otherwise specified)

Prior to the war, Cunard boasted the fasted ships afloat. White Star had given up chasing them, hence the all out, ridiculous opulence of Titanic and Olympic. If they couldn’t send you across the Atlantic the quickest, they’d make up for it with a new level of comfort. The problem was that the war, and then everyone being broke after the war, tied in with the reduced traffic heading to North America, meant that Cunard hadn’t updated her prized liners since. Mauretania, Lusitania’s sister, was built in 1907. Aquitania was finished in 1914 and they were still the ones running the prestige, express service into New York.

If Britain had sat still, others hadn’t. The record holder for the North Atlantic held the Blue Riband, and in 1929, Mauretania lost her two-decade old crown to the German liner Bremen. She tried to grab it back, and she got within three hours of doing it, but then along came another German ship, Europa who shaved it down by another half an hour.

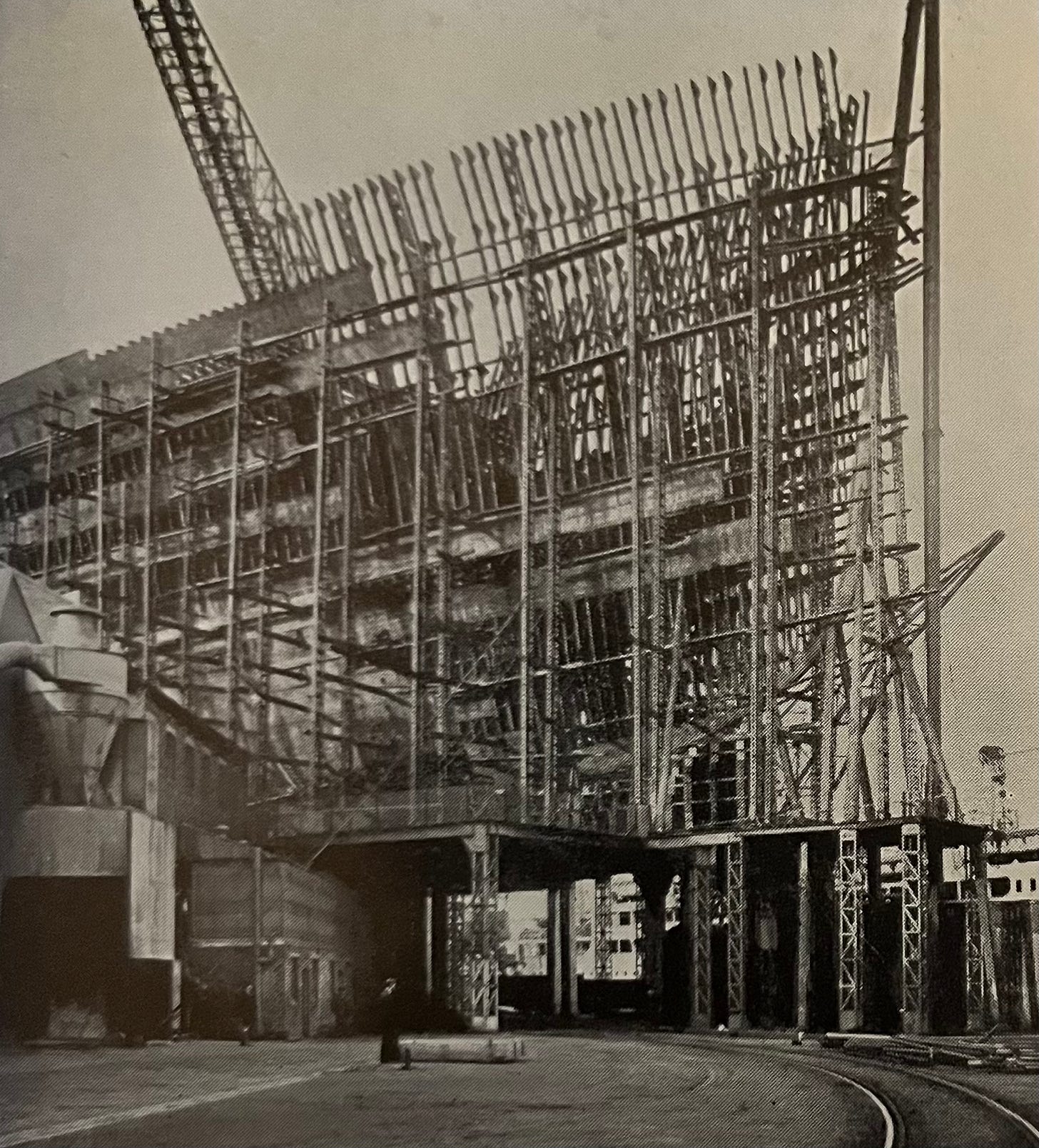

534 was so ridiculous, she encroached on unusual spaces at the shipyard.

At this point, Queen Mary still didn’t exist, despite that 1926 conversation. In 1930, John Brown’s on the Clyde were told they had the contract, but contractual shenanigans held up construction by another six months. At this point, she was known merely by her keel number: 534. Then there were issues in getting this ship insured. By the end of 1931, Cunard was haemorrhaging money and passengers crossing the North Atlantic had halved. Don’t forget, there’s been a Wall Street Crash in 1929 and a massive recession following. Work was halted on 534, the half finished hull, weirdly oversized for her surroundings, hung over the shipyard mournfully half built and Cunard found themselves in dire straits. So did White Star, who were also lumbered with an ageing fleet, and in spring 1934, the two companies merged their North Atlantic trade to secure government funding.

Finally, in September 1934, 534 was ready for launch. There had been some lame suggestions for name: Clydania, Leonia, Scotia, Britannia, Galicia, Hamptonia. The ‘ia’ at the end is a Cunard tradition, ‘ic’ belonged to White Star. That was a bone of contention since the merger, especially as technically she was a Cunard ship. There are some urban legends about the name going about. The public were invited to join in, and thought nobody reached the sublime heights of “Boaty McBoatface,’ like a few years ago when the same question was put out for another ship, some boot-licker did suggest King George V.

He was going to be there when she was launched. So was the Prince of Wales, and Queen Mary would be the one to do the smashing of the bottle and ceremonial. What if…

If you’ve ever been to Glasgow, you’ll know it rains every day. On 26th September 1934, it bucketed down. But we Brits are belligerent about the weather. It was a case of challenge accepted, and 30,000 odd people still turned out to see her slide into the water anyway. The Queen Mary was a beast. At more than 80,000 tons and more than a thousand foot long, nobody could be sure exactly what would happen when she hit the water. The thing all of the nerds at John Brown’s were trying to work out using tidal charts and calculations was how far she would glide when she went in, because lobbing something that heavy into the Clyde and just hoping for the best was dangerous. The estimate was 1194 feet, and the River Clyde had to be widened over 100 feet for a length of two miles. The river also needed dredging to accommodate her, and millions of tons of soil were dragged up and dumped out at sea.

This photo makes me immensely proud to be British.

The assembled crowd watched the Queen announce her namesake, and then:

‘Listeners in Sydney, Paris, New York, and Cape Town, as well as all over England, heard the Queen whispering: "Now I press the button?" and the reply, " Yes, that's splendid." For her voice had been picked up by the microphones and echoed round the world… as she pressed the button the thirty-thousand-ton empty shell of the white-painted liner began her journey to the waters, with the sound of creaking timbers and cheering, shouting, delirious Clydesiders echoing over the shipyard. Fifty-five seconds later she was afloat, proud and untamed, yet checked and held like a wild stallion in a corral, by two thousand tons of drag chains, many of which had been borrowed from other yards, and then seized by seven tugs, to be manoeuvred into her fitting-out basin.’

The hull slowed to a stop at 1196 feet.

This cartoon tries to convey the scale of the ship by superimposing it across Trafalgar Square in London.

When she was launched, Queen Mary was an empty shell. It would take nearly two years to finish her. Cunard White Star went for art-deco design, but erred on the side of conservative. She boasted two swimming pools, a shopping arcade, salons, libraries, childcare in all three classes, a lecture hall, and a massive dining room three decks high. There was even a Jewish prayer room, intended as a poke in the eye to Nazi Germany. When she finally sailed in 1936, the Mary was everything her owners had hoped for. She claimed the coveted Blue Riband a few weeks after her maiden voyage, and with a short interruption, would hold it until the 1950s.

When Britain declared war, the ship was halfway through a run to New York; packed mainly with Americans fleeing Europe. She spent the first winter laid up on the Hudson and most of her crew were sent back across the Atlantic. She was deemed too valuable. Who would risk such a prize being sunk by the enemy? Even then, there was a panic that some German agent in the US might try and sabotage here while she remained at New York…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Alex Churchill’s HistoryStack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.