FREE ARTICLE: Radiant May

Italy joins the First World War in 1915

You don’t go to war overnight. Maggismo Radioso literally means Radiant May and it refers to a dramatic burst of time in spring 1915, during which Italy hovered between signing a secret pact to join the Allies and actually declaring war on Austria-Hungary.

To recreate this period, I’ve used the diaries of Ferdinando Martini. At this time, he was serving in the Cabinet of Antonio Salandra as Italy’s colonial minister. This is a version of events through his eyes. He’s obviously got skin in the game, and personal opinions. Going out and measuring it against everyone else and putting it into context would be a PhD. Whoever decides to do it can have my notes, but this is how he experienced those days.

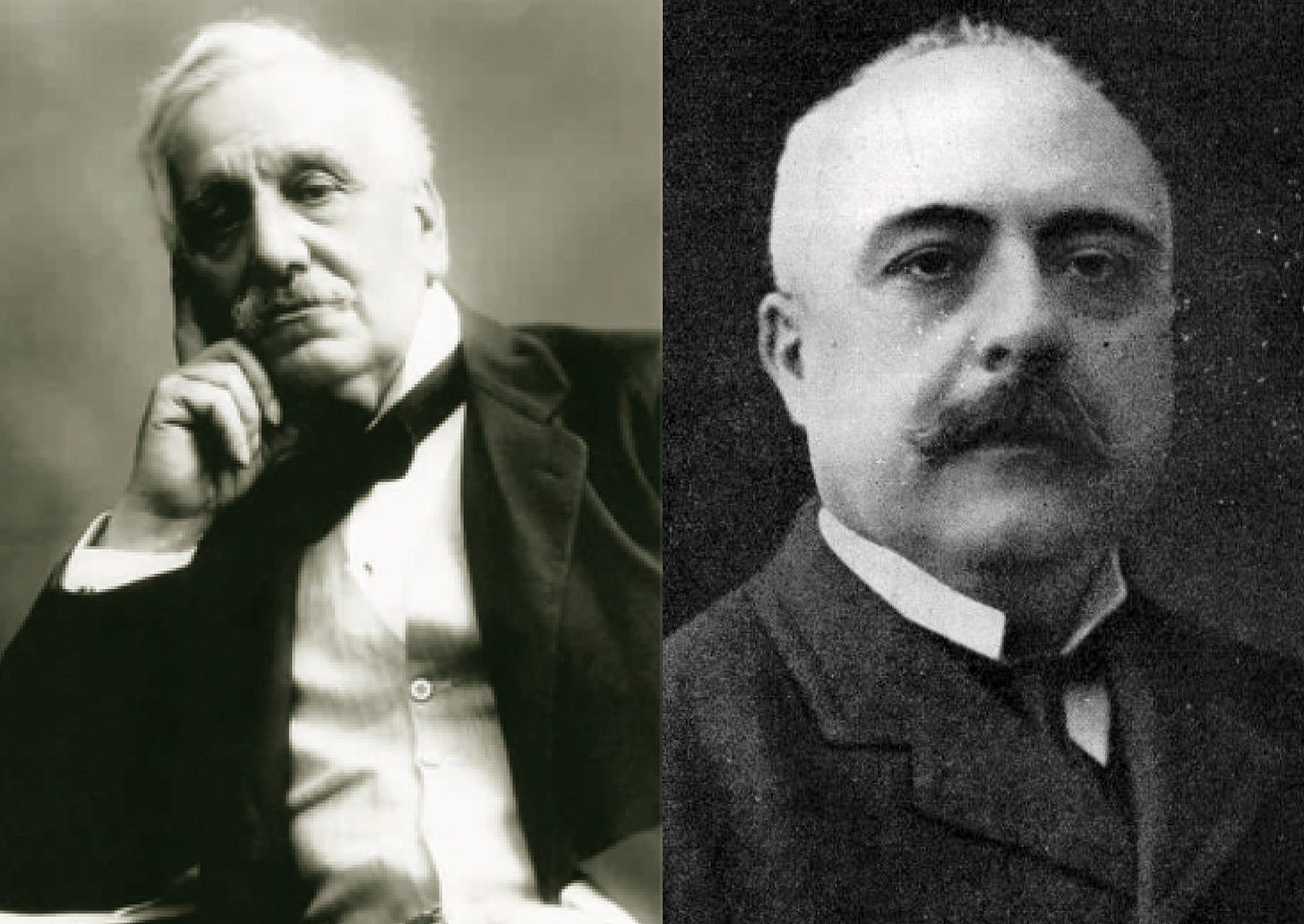

Left: Ferdinando Martini, diarist and Colonial Minister (Wikipedia) and right: the Prime Minister, Antonio Salandra, who had only been in office a few months when the war began in 1914.

The Background

Let’s not do a lengthy treatise on pre-war alliances; who said what, to who, and when. It’s not the interesting part of the story. This is the short version:

Italy had an old piece of paper that placed them in a gang with Austria-Hungary and Germany. (The Triple Alliance).

However, it was designed for defence. As in, if any of them were attacked the others were supposed to have their back.

But in 1914, those allies were both aggressors crossing other people’s borders.

So whether or not Italy was bound to get involved was up in the air. In Italian heads, anyway. The Central Powers were pretty insistent that there was nothing to discuss.

It wasn’t as simple as deciding whether or not to keep to the Triple Alliance, because there were specific issues with joining the Central Powers that threatened to have a dire impact on Italy. Pointedly, not wanting to get on the wrong side of the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean was a sensible excuse to steer clear of the whole thing. Nobody runs up to the biggest kid in the playground and kicks them in the shin unless they’re of unsound mind. One of the others was that inconveniently, two thirds of Italy’s coal was sold to her by Britain. No industrial nation on earth could function without their coal in 1914. No power, no trains, no factories. Economic meltdown and human deprivation.

And so on balance, Italy did the sane thing and stayed neutral in 1914. There’s a lot more to this, but you’re going to have to read it in the new book I have coming out next year with Nicolai Eberholst. It’s called Ring of Fire and it’s about the opening weeks of the war.

Suffice to say, Ferdinando Martini was relieved by neutrality, and that this was how on the whole, he also gauged wider reaction. ‘The country seems to welcome the decision taken by the Government,’ he wrote in his diary on 1st August, ‘namely not to participate in the war.’

The Battle to Remain Neutral

Enemies are easy. Find them. Shoot at them.

Allies are annoying. Trying to stay friends with them when you want different outcomes, have different priorities and are in a fight to the death while you’re tied together is a nightmare.

Neutrality is a complete pain in the a*se. If you’re of substantial importance, like Italy as an imperial power certainly was, you’re going to get grabbed at by all sides by people who want you on their team, who want your resources, and want you to share the burden they have been saddled with in fighting, supplying and paying for said war.

Trying to navigate neutrality, you risk p*ssing everyone on both sides off at once. It is an exhausting process. Before spring 1915, Italy had been fending off all kinds of different interests. Prime Minister Salandra was pro ally. He wanted Martini to cosy up to Sir Rennell Rodd, the British Ambassador in Rome, to improve Anglo-British relations as soon as the war broke out. Internally, it seemed every elected deputy in parliament wanted to make himself heard, too. Martini was particularly irked by one, who talked at him ‘for three hours, saying that we must in any case try to get out of the neutrality that leads us to ruin, and unite quickly with the armies of Austria and Germany.’ Austro-Hungarian and German representatives were not gentle in attempting to prod Italy towards their commitment to the Triple Alliance. As far as the latter were concerned, these overtures came from no less than former Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow, who had been summoned out of retirement to bring Italy into line. Pressure was also being applied on the King, Victor Emmanuel III. He was a constitutional monarch, he acted on the advice of his ministers, but regardless, the Kaiser sent him a long telegram imploring him to honour the Triple Alliance.

Martini found the King puzzling. He best articulated the problem of his lack of presence when he said: ‘The King has the flaw of being too... how should I put it? Modern. He himself does not believe in Monarchy or at least in the future of monarchies; if he was born bourgeois he would be a republican and perhaps a socialist. He is intelligent and cultured; but by dint of not believing in his own strength he ended up losing it. Today no one cares enough about him, to know, in such grave moments, what his opinion is, what goal he is aiming for, what path to follow: if anyone thinks about him it is to complain that he does not assert himself, that he actually hides…’

In terms of the army, Italy had been preparing since the onset of war. When you think about it, to do nothing and hope for the best would have been negligent. Defending yourself is one thing, but by 18th August 1914 offensive Italian war plans had been existed with Austria-Hungary as the target. Martini was unimpressed at this eagerness. ‘Thinking that Italians can go to Vienna in three leaps is heroic evidence of imagination.’

One of the major reasons for staying out of the war initially, was that the Italian Army was nowhere near ready to go to war, however much generals wanted to. They needed to at least stall for time. In the first month of the war, Martini was told that if the entire army was mobilised in August 1914, two thirds of them would not have uniforms. (Yet again, details in the book next year) This was not the case by April 1915. On 21st, the War Minister declared that the army was ready. ‘Today,’ wrote Martini after their Cabinet meeting, ‘we have 700,000 men under arms: with the recall of other classes we will reach a million and a half, including the territorials.’ (Having said all this, Italian troops were already fighting in Africa, and had been since 1914, once again, this is in the book next year)

Stuff.

Just finally, before we get to the action, a bit on why Italy would bother getting involved at all. All of those essays we did at school in the UK where you had to write about Social Darwinism and the naval arms race are a bit of a waste of effort. In short, stuff is the evil behind it all when it comes to the causes of the First World War. Almost all of it can be boiled down to stuff nations wanted, and stuff which others were desperate to keep. Normally, pursuing stuff was a cagey endeavour and you had to be careful lest you provoke a war.

Now there was a war anyway. Whichever way it went, the map was going to be redrawn when it was over and stuff would be up for grabs. In theory all you had to do, if you were Italy, was volunteer your services to the right side, having negotiated that the stuff you wanted landed in your lap when victory was assured. Then rather than grabbing said stuff, you’d simply be getting what you deserved for all your hard work. And no judging. Because this is exactly what Britain and America were playing at. So were Japan, (masterfully) Portugal, and countless others. If you wanted to be a “Great Power,” as in have an Empire, you needed to be in the war. Otherwise, no seat at the table for you when all the stuff was being divided up at the end.

Italy did have an Empire, but there was more important stuff on their doorstep. Italy had only been a unified country for fifty odd years in 1914. Italians known as irredentists very much considered themselves still incomplete as a nation. There were areas that were still outside Italy’s borders, but were ethnically very Italian. Austria-Hungary had possession some of them. Now you see another major reason why Italians fighting on the side of the Central Powers was problematic. If nations on the same side want the same stuff, it causes trouble and incites underhand f**kery most foul.

The place that Martini keeps coming back to in his diary is Trieste, in Istria. This was a prize that Italy very much wanted, and considered rightfully theirs. The likelihood of Austria-Hungary giving it up was basically non-existent. The population was about 38% Italian speaking, and nearly 44% Serbo-Croatian. There is no room for facts and logic in Imperialism. For Italy, what mattered was that up until Istria was seized by Napoleon in 1797, then handed off after his demise to Austria in 1815, the area had been part of the Venetian republic since the 1200s. (Library of Congress)

And so this is why Italy as a state had a vested interest in getting involved. ‘Italy has been waiting for its true national war since [1866] wrote Martini in his diary, ‘to finally feel unified and renewed by the united action, by the identical sacrifice of all her children.’ Surely, then, it was just a matter of time before Italy was drawn into the First World War.

Secrets, lies, unrest and ‘giolittismo’

By mid-April 1915, Ferdinando Martini was plagued by insomnia, anxiety, and a general concern about the future. The government was getting to the point where they were going to advise the King that Italy needed to join the war on the side of the Allies. They were negotiating secretly with Britain, France and Russia, but whilst this went on in the background, with the lack of information being put out, people were drawing their own conclusions, and it was sending parts of the country into a paranoid panic.

In fact, as far as Martini was concerned, von Bülow, wily diplomat that he was, was using their silence on the subject of the war to manipulate perceptions. He was filling the void left by Salandra and his government with his own news. ‘Bülow makes one believe that everything is arranged between Italy and [Germany] and the silence of the Government is taken by some as proof that the news is true.’

Parts of the population were by now obsessed with the idea that Germans living in Italy were preparing a coup. Disorder was mounting. Martini had heard of violence and/or protests in Tuscany, San Miniato, and Empoli. Newspapers fanned suspicion, ‘supposing, probably rightly, that they were the work of German agents and money.’ Of the industrial unrest in Tuscany, Martini asked, ‘What other motives could the workers have had? The German cloth factory owners probably incited and pushed them.’ The town of Prato, where it had happened; was that not the home of the anarchist who assassinated King Umberto I?

Socialists were vocal opponents of Italian intervention too, and planning ‘a solemn anti-war demonstration for 1st May.’ Schemes were being discussed for valuable works of art and items of cultural significance to be withdrawn from cities like Verona and Venice. Martini had been to Florence and missed a cabinet meeting , and was even starting to doubt his own colleagues. ‘I am sure that things are almost at the point where I left them when I departed: I am sure that no agreements are possible with Austria; however tomorrow if possible I will see Salandra or Sonnino.’

The strain was having a detrimental effect on the country. ‘It’s impossible to go on like this,’ wrote Martini in his diary, ‘chatter, the dissemination of false news, malicious insinuation… And so the confusion increases and heads become more and more broken every day, no longer knowing who to believe. We have to get out of it.’

Left: War Minister Sidney Sonnino; Middle: The thorn in the government’s side, former Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti; Right: national celebrity Gabriele d’Annunzio.

Clearly, Italy was going to have to make a decision. Salandra’s government had been talking to the Allies throughout the war so far, but had also been keeping in touch with the Central Powers. Whatever way you spin it, everyone was back-stabbing everyone else in some way as they sought to bank as many options as possible. It wasn’t only Italy in play. Bulgaria was still up for grabs as a partner, and Romania, and you couldn’t keep them all on side. Some of them wanted the same stuff, and conflicting promises were being made.

That anxiety that Martini was feeling, it came right in the middle of a last, secret push by Italy to come to an agreement with the Allies. What was really screwing with Martini’s head was the fact that even if they managed to pull this off, Italy was far from united behind the idea of Italy going to war. ‘The pressures of the neutralists are stronger every day,’ Martini wrote on 17th April. ‘The Vatican also urges the Government to peace.’ The King was still keeping his mouth shut, or when he did open it, remaining absolutely unreadable. 'Although he appeared convinced of the necessity of war, [he] still does not express himself.’

In a constitutional monarchy, it is the done thing that the King, in this case, follow the advice of his elected ministers. For example, in Britain, no monarch has not done this since the early 1700s. If you overruled them, the likely outcome was that your democratically elected government would quit, because clearly the arrangement is unworkable. At that point the King would have massively overstepped his remit. The possibility that Martini and his colleagues would have no other choice but to resign was becoming real, if they planned a pact with the Allies and then Italy didn’t see it through. ‘Salandra has already told [the King] that the Ministry is ready to withdraw, should His Majesty believe it has another path than the one that the Ministry considers the only good one.’

When Austria-Hungary came back with improved stuff concessions, Martini’s opinion was firm: ‘Naturally - since this does not satisfy our legitimate desires, nor resolve the serious questions we have raised - there is now no other way than war. The deal with the Allies, the Trattato di Londra, was finally signed on 26th April, promising Italy all manner of stuff at the end of the war, and adequate support to fight on land and at sea. In return. Italy was supposed to join the war on the side of the Allies, against all of their enemies.

Martini and his colleagues were now trying to achieve a delicate balance. They didn’t want it getting out that they already had a pact with the Allies before they had publicly detached the country from the Triple Alliance ‘for moral reasons.’ The chances of keeping the London document quiet for long were not good. Within a couple of days the King of Greece had heard rumours that Italy was in talks with Britain. The Italian representative in Athens was not lying when he said he had no idea.

On 3rd May Italy officially left the Triple Alliance. Martini was distraught after the council meeting on 7th May: 'The most serious, the most solemn, among those held since the Kingdom of Italy existed: gravity and solemnity that come to our deliberations from the terrible, tragic situation in which Italy finds itself: to be a great Power or not to be:…’ The council was not unanimous by any means in the belief that war was the only path for Italy to take. Pasquale Grippo, the education minister, spent some of that day pleading with Martini. ‘[He] makes us consider that the war is not wanted by the Vatican, it is not wanted by the socialists, it is not wanted by a large part of the bourgeoisie: and, I die.’

The council of ministers decided to publicly announce that owing to the severity of the situation, none of them would be leaving Rome. Martini seemed to think this would be viewed positively, but he was mistaken. ‘The effect was different from what I expected… I’m somewhere between furious and dismayed. Others are shouting that everything is arranged with Austria. A great confusion; the Ministry's authority suffers greatly as a result.’

For Martini, the arch-villain in all of this was former Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti, the man replaced by Salandra in 1914. Giolitti was a powerhouse in Italian politics, and in spring 1915, he was adamant that Italy remain neutral. He thought the army was ill-prepared. He had, Martini wrote, ‘no faith in the country's resistance, because the Italian soldiers are fleeing as they fled in Africa, forcing him, Giolitti, to struggle to invent heroic acts, falsifying telegrams. These are, reported by Salandra, verbatim words of the former Prime Minister.’

Giolitti had returned to Rome urged on by like-minded politicians, and he was ready to shout very loudly, and very publicly for his cause. He was adept at political machinations, and the majority of those in the Italian parliament came out publicly to side with him. 'Giolitti's arrival on the scene has revived spirits in the neutralist camp,’ wrote Martini in his diary, ‘which is preparing for the final tests and the saddest violence.’ He was proving to be a rallying point for those who wanted neutrality. At midnight on 10th May, Martini wrote:

‘Horrible day… The Chamber is [a member] tells me, in an agitation the likes of which we have never seen. Violent intentions against ministers, expressed with equal violence of language. The invectives against Sonnino were most angry… The nervous excitement, not only of the deputies, but of all the appendages of the political world is at its peak and benefits the conspirators…’ The following day, he described as ‘among the saddest of my life… it is irrefutably established that the (very notable) majority of the Chamber is close to Giolitti and does not want to know about the war.’

The cabinet stared down the barrel of their own resignations, based on the opinions, so Martini saw it, of people who knew nothing about what had been going on behind the scenes. What made Giolitti’s stance so utterly incomprehensible for the colonial minister was that he did know. The Government had briefed him themselves, via the treasury minister in the hope that a full appreciation of the situation would shut him up. 'That he is against the war matters little… he who knows everything, who knows the commitments undertaken by Italy with the Triple Entente, you continue to propagandise a neutrality that cannot be maintained without Italy descending below the minor republics of South America, it's too much!’ This is a common refrain in Martini’s diary. He believed that if Italy declined now to stick to her word, her position would be lesser on the world stage than an unimportant nation in South America.

On 12th May, Il Giornale d’Italia published a scathing indictment of both Giolitti and neutrality:

‘This is the environment, this is the state of [things]: Press widely paraded to oppose the Government's program and help in the overthrow of the Government itself: parliamentary conspiracy on the one hand, on the other other newspapers fervent supporters of that program and popular masses moving through the streets, fighting in the squares to support it. If there is no external war there will be civil war. But, by renouncing the war, Italy renounces not only the dominion of the Adriatic, not only the unredeemed lands, it renounces its own honour.’

The entire cabinet was now staring down the barrel of resignation. If all of their work was to be ignored, if the King was not to follow the advice of his ministers and support them, if Italy was to abandon the agreement with the Allies, then there was no other way, they all agreed. ‘The important thing is that it happens quickly, because the country is nervous.’ On 13th May, Salandra led the resignations and Italy was technically without a government. What was going to happen, who would replace them? ‘The effects that our resignation can and will produce,’ wrote Martini, ‘are incalculably serious.’

Radioso Maggismo

When he turned in for the night on 12th May, Martini knew that someone else was on their way to Rome. ‘D'Annunzio arrives this evening and I fear turbulence which, as we know, becomes contagious.’ Turbulence, he was expecting, the outcome, he was not.

Aristocrat Gabriele d’Annunzio was one of those men of letters; poet, playwright, author, journalist, politician. You know that old stereotype of the colourful, womanising, and verbose Italian stud? This is him. He was immensely famous and immensely unimpressed with Austria-Hungary’s possession of those disputed territories. He’d moved to France, and for the first part of the war he had been reporting on it from there. He was already firmly of the opinion that Italy’s rightful place was alongside the likes of Britain and France, and not afraid to say so. When he arrived home on 12th May, Giolitti was about to meet his match. If he had rallied the neutral contingent, now the interventionists out on the streets calling for Italy to join the war had a celebrity to get behind.

Giolitti was not a beloved public figure, courting the opinion of the masses was not his way of doing things. As well as his numerous other talents, d’Annunzio was also a gifted orator, and he wasted no time at all on his return to Rome. ‘One hundred thousand people accompanied him to the Regina hotel,’ wrote Martini, ‘it was not one of the usual demonstrations: serious people told me: since Garibaldi's arrival nothing similar has been seen. He spoke from a balcony and spoke well.’

D’Annunzio was by no means done campaigning. This image from May 1915 is of him giving another speech in the Constanzi Theatre in Rome. It is titled: ‘The great demonstration against the “giolittismo”'

This was Radiant May. D’Annunzio might have been courting a minority, but he stirred them up with skill. In a few days, Giolitti was swept away, and in a plot twist, in part, it was because it turns out that Ferdinando Martini had teeth.

QUAI D’ORSAY

Within days, the colonial minister had recorded that Giolittism, though still feared, was losing ground. ‘There is an awakening in the national conscience: the country feels offended by the Bulow-Giolitti intrigue and is very irritated by this fornication of theirs.’ His claims were certainly borne out in L'Idea Nazionale. ‘Who betrays the King?’ Asked one article. Evidently, in their opinion, Giolitti had done so by coming in between the Victor Emmanuel and the advice of his ministers:

‘He who prevents the King from making use of his prerogative betrays the King. Our constitution… attributes to the King the prerogative of representing the State, of protecting the rights of the State in supreme international relations.… Up to now the King, through the ministers responsible for him, designated to him by the trust of Parliament, has made good use of his prerogative. Now a parliamentary pronouncement, led by Giovanni Giolitti, would like to prevent him from exercising it, would like the King to strip himself of his prerogative and for Parliament to discuss and decide on a matter that affects not only the interests of Italy but also the interests of others States, which have dealt with us, confident in our international and constitutional loyalty.’

On the morning of 14th May the news was released of the wholesale departure of the Council of Ministers. The state of affairs is very serious,’ wrote Martini. ’The news of the Ministry's resignation made an enormous impression. Very serious events are threatened.’ He was not exaggerating. That day, pro-war students arrived at the seat of parliament and attempted to set fire to the doors, got inside and smashed furniture:

‘The people understood: and, having known the intrigues between Giolitti and Bülow, they felt offended by the domination of a German ambassador, they rose up in a fit of anger against those who, by hindering the work of the Government, trafficked with the foreign diplomacy… There is such a ferment in the city that I don't remember. "Betrayal, betrayal" sounds the common voice.’

Giolitti did try to defend himself. According to Martini, who obviously wasn’t impartial: ‘by having him say that he was unaware of the denunciation of the [Triple Alliance] and [Italy’s] commitments to the Triple Entente. He lies as always, because he was informed of everything by Carcano, (the Treasury Minister) as Carcano himself attests.’

His voice was barely heard. The fact that German representatives were proudly proclaiming that he was about to return to power did Giolitti no favours. ‘They throw brimstone on the fire here.’ The chants on Rome’s streets were brutal: "Death to Giolitti,” “Treason," "Long live the war.” These slogans were already being printed on leaflets and being widely distributed. To crown it all, wordsmith that he was, people were repeating a slogan of d’Annunzio’s. He’d fully mobilised favourable allies in control of newspapers. ‘May the Roman press help us to prevent, by all means, a handful of fraudsters from being able to dishonour Italy.’

At 3:00pm the King, who was being accused of colluding with Giolitti, called the man himself to see him and invited him to form a government. At this point, Giolitti baulked. He said that under the circumstances, he could not replace Salandra, because he feared that unrest on the streets, which now extended to burning effigies of the Kaiser, would only escalate if he took power. The next option couldn’t carry a ministry, and at any rate, said "I am more of an interventionist than Salandra because I would have declared war on Austria as early as August.” Carcano was called in next. ‘Your Majesty,’ he responded, ‘order me to go by submarine or by airplane to fight and I will go: but as for creating a Ministry, let's not talk about it: after all, I agree in everything with my colleagues of the Salandra Cabinet,’ Looks like nobody wanted to take this on.

That day, Martini wrote in his diary: ‘I believe today that there is only one way out: the recall of the Salandra Cabinet.’ Salandra concurred. As they were leaving the Ministry of the Interior at Palazzo Braschi, they were already conversing about adding some ministers without portfolio to the Cabinet. ‘This is what the country is now asking for,’ recorded Martini, ‘not for us, poor people, but for Italy’s honour and her dignity.’

On streets across Italy, people were still out in force demanding war, calling: Death to Giolitti. ‘The demonstration such as I have never seen the like of: more than one hundred thousand people.’ These are some pretty big numbers being touted by Martini. These scenes were impressive, and worrying, but they did constitute a minority. Much like the crowds that took to the streets of London or Berlin in 1914, there were a lot of young men, a lot of students, and not everyone condoned their behaviour, regardless of their opinion about Italy’s involvement in the war. You can’t apply the same response to the outbreak of war to everyone.

Away from Rome, Martini was relying on second hand information. ’Serious events occurred in Turin during and because of the neutralist demonstration,’ wrote Martini. ‘There are dead and injured: one dead in Palermo too, one in Genoa.’ Even here there is more to the story. On 16th Mary, a nationwide Socialist conference that was in progress discussing whether to carry out strikes or not. In Turin, this disorder was mixed in with both pro-war and neutralist demonstrations facing off against each other. Chaos reigned for 48 hours.

Socialist led protests in Turin in May 1915 (Museo Torino)

On 17th May, long lines of protestors wove through the streets in procession on their way to attend a massive rally led by Socialist leaders. By 10:30am, cavalry had been ordered to charge the crowds. A young man by the name of Carlo Dezzani was killed, and about a dozen more were injured. By 3:30pm, a group had looted a weapons shop and were in a shootout with police. A General on hand ordered the storming of the Casa del Popolo, a public building, which had been trashed. Here, Socialist leaders drew a line and invited their protestors to return to work. By 19th May, the drama was over.

In Rome, these two days proceeded very differently for Ferdinando Martini. He and his colleagues were to remain in government. If he is accurate, in the capital the crowds were stark contrast to those in Turin. ‘Splendid unforgettable day on May 16th,’ he wrote, ‘with the display of such harmony and such an outpouring of patriotic affection.’

Efforts now revolved around how to actually declare war on the Central Powers. Saccharine telegrams were going back and forth from London and Paris. Salandra had already moved on from his near downfall in his thinking. He wrote to Martini, ‘Dear Friend, the members of the Chamber tell me that we need, in our declarations, a warm appeal for conciliation, for harmony, for oblivion of disagreements, etc. etc.’ What Italy needed now was unity.

It’s easy to be magnanimous when you’ve won. ‘I don't want people to talk about oblivion,’ Martini insisted. ‘Giolitti’s conduct can be forgiven, if the people feel inclined to forgive.’ He stopped short of writing off their rival’s behaviour. ‘It must not be forgotten: it was characterised as treason, it was branded as turpitude. Either he was such or he wasn't: if he wasn't, let's say it and let's absolve Giolitti from the accusations that he didn't deserve: if he was, let's not commit violence, let's not talk about it, perhaps, but let's not invite the people to forget.’

Giolitti left Rome. When he did so, the authorities told him that if he did not accept a large security escort, they would not take responsibility for his personal safety. He spent the rest of the war in a sort of voluntary exile. The Italian people did forgive him, and they were prepared to forget. He still had one more term to come as Prime Minister after the war. As for d’Annunzio, he had a passion for aeroplanes and despite being in his 50s, served as a pilot during the war.

Italy declared war on 23rd May, but only on Austria-Hungary. They would no do so to Germany for another year.

I will definitely come back to Martini and his diaries at some point. I like the way he writes. And my Italian is getting better and its not so tortuous trying to read them…

Very interesting read on era that I know little about.

That is an excellent read covering an aspect of WW1 that I want to learn more about.