FREE ARTICLE: War Factories

‘What is America but a land of beauty queens, millionaires, stupid records and Hollywood?’

Don’t get angry at me, that subtitle is a Hitler quote. And he got what was coming to him.

I still get asked about War Factories all the time. People are genuinely fascinated by factories and how industrial progress all over the world fuelled the Second World War. I thought I’d give you some insight into the story that led the production company on a path to making the programme. And for that, we have to go the United States at the beginning of the war…

America was in no way ready to fight any significant army when the war began. Having forged an expeditionary force of more than two million men by 1918, the US Government let it rot. Manoeuvres carried out in August 1939 were a Laurel and Hardy affair, embarrassing. Such was the determination not to take part in any major conflict, that any potential American army was starved of cash and resources in the inter-war period, so that it was fit for no modern conflict by 1939. The threat of America’s infinite manpower could come later, when men had been recruited, equipped, trained, shipped abroad and had gained experience of combat. Arguably the more terrifying concept for the Axis Powers at first was what America could send to her newfound allies before that happened.

The potential for American industrial capacity was enormous. Because mechanised warfare requires stuff. A lot of stuff. But that is just the beginning. That stuff gets destroyed, lost, broken, shot down or sunk. Then you need to produce it all again. In the end, 2/3 of everything produced by the Allies came out of America. That included 86,000 tanks, 286,000 aeroplanes. 8,800 naval vessels 5,600 merchant ships, 2.6 million machine guns and 41 billion rounds of ammunition. In 1939, however, little of the capacity for all of this existed.

So when did the penny drop? When did it become obvious that refusing to participate; refusing to even be ready to manufacture what America might need to participate, start looking like it could turn out to be unforgivably naive? And who was behind the change?

The first thing to know is that Pearl Harbour is not quite the seismic watershed that you think it is for America. Though she remained neutral until then, unlike in 1914, by December 1941 there was no question as to what side would be picked if that neutrality came to an end.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed a War Resources Board when Poland fell in September 1939. Industrialists he sought out got six weeks of work done, examining what America would need to do to get ready for participation in war, before the group had to be disbanded. Public opposition to even considering such an eventuality was overwhelming. He was unable to challenge the determined isolationism permeating throughout American politics and society. In fact, he’d rather retire than take this on.

Then Hitler began a huge invasion of Western Europe. In a few days it was clear that France was about to fall. Leave it to Winston Churchill to ram the scenario in Europe home by weaving the potential consequences into a terrifying telegram that he send to Roosevelt:

TO PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT from FORMER NAVAL PERSON. 15.5.40

Although I have changed my office, I am sure you would not wish me to discontinue our intimate, private correspondence. As you are no doubt aware, the scene has darkened swiftly. The enemy have a marked preponderance in the air, and their new technique is making a deep impression upon the French… Up to the present, Hitler is working with specialised units in tanks and air. The small countries are simply smashed up, one by one, like matchwood. We must expect, though it is not yet certain, that Mussolini will hurry in to share the loot of civilisation.

We expect to be attacked here ourselves, both from the air and by parachute and airborne troops in the near future, and are getting ready for them. If necessary, we shall continue the war alone, and we are not afraid of that. But I trust you realise, Mr. President, that the voice and force of the United States may count for nothing if they are withheld too long. You may have a completely subjugated Nazified Europe established with astonishing swiftness, and the weight may be more than we can bear.

All I ask now is that you should proclaim non-belligerency, which would mean that you would help us with everything short of actually engaging armed forces.

Immediate needs are:

First of all, the loan of 40 or 50 of your older destroyers to bridge any gap between what we have now and the large new construction we put in hand at the beginning of the war. This the next year we shall have plenty. But if in the interval Italy comes in against us with another 100 submarines, recent we may be strained to breaking point.

Secondly, we want several hundred of the latest type of aircraft, of which you are no getting delivery.

Thirdly, anti-aircraft equipment and ammunition, of which again there will be plenty next

year, if we are alive to see it.

Fourthly. the fact that our ore supply is being compromised from Sweden, from North Africa, and perhaps from Northern Spain makes it necessary to purchase steel in the United States. This also applies to other materials. We shall go on paying dollars for as long as we can, but I should like to feel reasonably sure that when we can pay no more, you will give us the stuff all the same.

Fifthly, we have many reports of possible German parachute or airborne descents in Ireland. The visit of a United States Squadron to Irish ports, which might well be prolonged, would be invaluable.

Sixthly, I am looking to you to keep that Japanese dog quiet in the Pacific, using Singapore in any way convenient.

The details of the material which we have in hand will be communicated to you separately.

Roosevelt had already begun to take action. ‘If you don’t do something,’ warned Army Chief of Staff, General Marshall, ‘and do it right away, I don’t know what’s going to happen to the country.’

The President was told that if Hitler landed five divisions anywhere on the coast they would run amok. That wasn’t even contemplating the simultaneous threat emerging from the direction of Japan. Yes, Roosevelt heard, the army needed men, but crucially America was also going to need stuff in huge quantities; planes, bombs, ships, ammunition, tanks.

Stuff.

So who you gonna call? No. Not Ghostbusters. America’s leading industrialists; men that had made their fortunes honing mass production techniques, taking on huge projects and literally delivering the goods. His first choice turned him down. He was 69, and not convinced he could take on such a monumental task. Who, then, should I ask? Replied Roosevelt. Name me the top three men in industry right now. The answer was emphatic.

‘First, Bill Knudsen. Second, Bill Knudsen. Third, Bill Knudsen.’

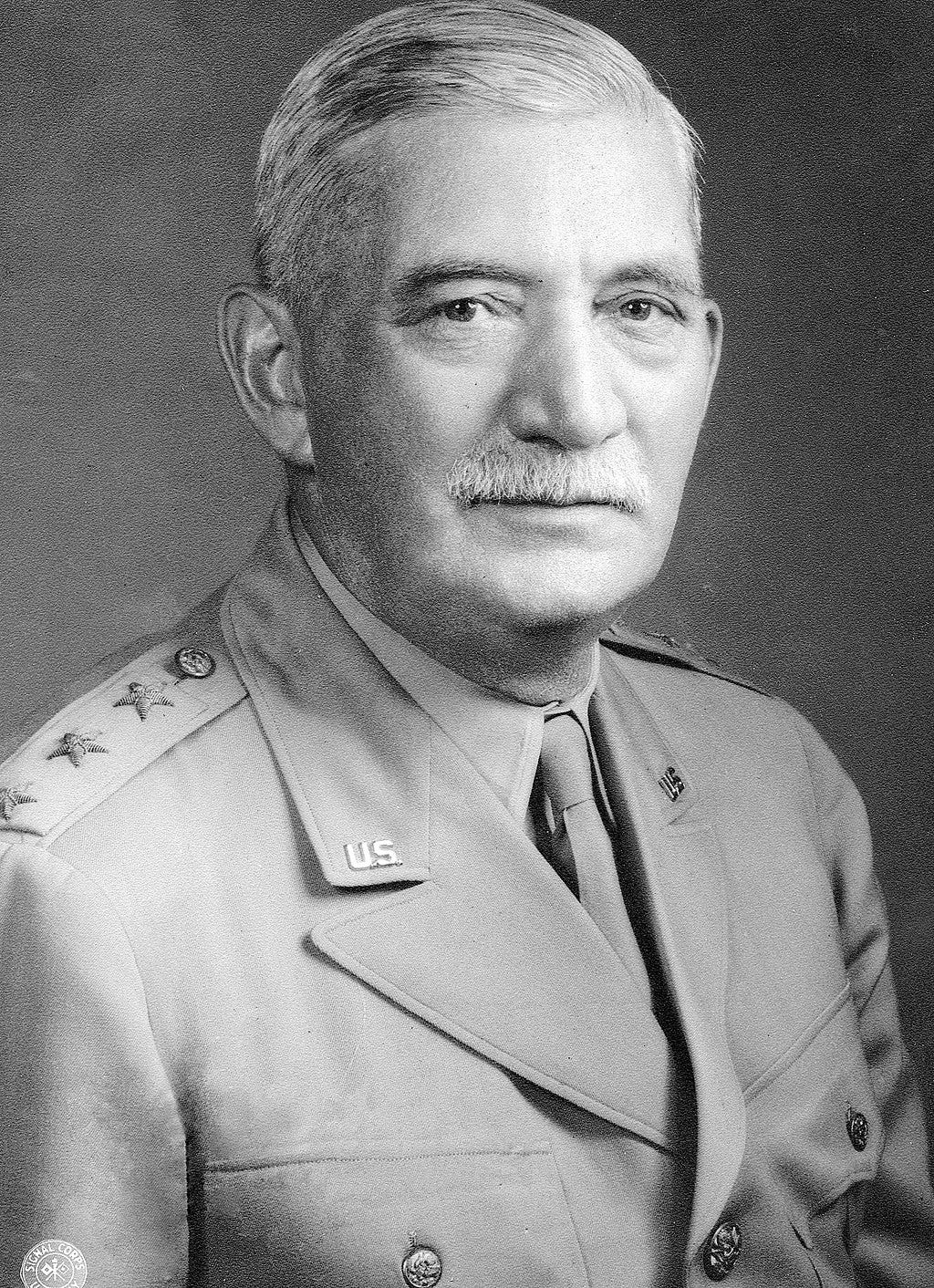

A Dane, William Knudsen was a self-made man. He’d arrived in America aged 20 with $30 to his name, leaving behind a massive family (he was one of ten) in Copenhagen. Mechanically minded, he wanted the American dream, and he was prepared to work his tail off to get it. He started off drilling holes in steel plates in a navy shipyard, and by 1940 he was the top man at General Motors. That was until Roosevelt convinced him to leave and take the lead in rearming the USA.

William Knudsen (US Army)

A phenomenal businessman with decades of experience in streamlining manufacturing processes to get maximum output, his family thought he was nuts when he told them he was going to do it. General Motors were livid that he intended to abandon his post when America wasn’t even in a war, and he didn’t yet know what the President wanted him to do. His response was simple: ‘This country has been good to me, and I want to pay it back.’ It was just as well, because Roosevelt told him he’s be working for free.

At the head of the new National Defence Advisory Commission, charged with getting America ready for war, Knudsen broke it down like so: he needed a team of people who were experienced with mass production techniques and trouble shooting them. Then he needed to prioritise what America needed. With an overwhelming list, he put the things that took longest first; like ships and tanks. Further down the line for organisation were quicker items like rifles and uniforms. By October 1940, Knudsen had signed nearly 1,000 contracts with more than 500 companies overseeing $9 billion of spending for the army and navy.

But Knudsen did not only have to prepare America for war. You might hear the phrase the Arsenal of Democracy. America had allies to help. France had fallen, and Britain could be next. Facing Hitler alone was not an attractive prospect. For the likes of Knudsen, this was as vital as producing material for America to use. As an indicator of the job in hand, take one item: aircraft. At the beginning of the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940, America was producing 550 a month. 250 of those were for shipping abroad. Britain was asked what she needed, and the answer was 1,000. But actually, providing that she was not trampled into dust by the Nazis, a more realistic figure was going to be up to four times that.

It was a running joke that anyone with a lathe who could make it to Washington could get a government contract at this point, and there was one man in particular who desperately wanted some of this action. A poll in 1945 ranked the son of an immigrant shoemaker, Henry Kaiser, just below Roosevelt himself in the ranks of civilians who won the war. Growing up in upstate New York before cars were even a thing, Kaiser dropped out of school and started out in the photography business with five dollars that he borrowed from his sister. By 1913, he began his own business scraping out modern highways, laying down hundreds of miles of road. By 1940, he had not only changed the face of the Pacific Northwest and California, not to mention Cuba; but had headed up the project to build Hoover Dam.

Henry J. Kaiser (California Museum)

In 1940, whilst Knudsen was attempting to get America’s massive auto industry more involved in production, Kaiser was puzzling out how he might get involved. Knudsen favoured big business. It was where he came from, and he reasoned that large companies hired the best people. With so much to be done, eventually, though, an opportunity presented itself for Kaiser. He had carried out a minimal amount of shipbuilding, but now, a call came in for emergency ships for Britain, and he was determined to build them. In this scenario, with Britain paying, he was less likely to face opposition from Knudsen.

A full year before Pearl Harbour, Kaiser signed a landmark peacetime contract, to launch an endless stream of ships to an identical design. Overhauling empty mud flats north of San Francisco at Richmond, California, Kaiser had the ground drained, covered in rock, concrete and gravel in three weeks. During which it did nothing but rain. In the meantime, Kaiser’s son Edgar was on his way to Portland 900 miles away to transform eighty acres of desolation into another yard. At the end of March, buildings had already begun going up. Like father, like son. It’s worth pointing out another huge challenge, too, that if there was no giant shipyard on these sites before 1941, then there was no deluge of shipbuilders hovering nearby, either. This huge volume of ships were going to have to be built by inexperienced labour.

Robert Lasalle, an Italian-born immigrant, at work in Richmond, California. Originally a barber, he had been working at Kaiser’s shipyard for a year at this point. (US Office of War Information)

In the meantime, Knudsen advocated that the same ship be adopted by America herself. Kaiser’s California shipyard was about to become a standard model for more all over the country. What they would be doing was already going on in Britain; taking sections of identikit ships and plugging them together rapidly. The advancement was how they’d be stuck. As opposed to rivets, which required more skill and more time, these ships, the Liberty Ships, would be welded in place. This hugely simplified the process, meaning less building time, and crucially meaning that more companies could build them. Again though, men and women would have to be trained to do it. In an average of 45 days from start to finish, as opposed to months. Kaiser’s Richmond yards produced 747 ships by the end of the war. One of them, in a competition in 1942, was built and launched in four and half days. It took the record from Edgar, who had turned one out in ten.

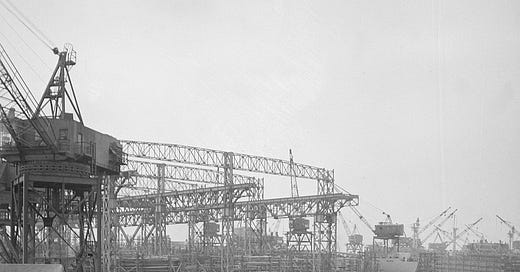

A collection of Liberty Ships under construction at another site in Baltimore (US Office of War Information)

Steel plates being welded into sections for assembly. (US Office of War Information)

Henry Kaiser didn’t care what sex his workers were, or what race. He just wanted the maximum output her could get from his yards. The Library of Congress cites 6,000 black workers on the site at Richmond, about 1,000 of whom were women. He also put up medical facilities and treatment for his workers and their families, as well as leading humanitarian efforts for Europe.

Eastine Cowner, a former waitress, working as a scaler on the construction of the Liberty Ship SS George Washington Carver. The ship was named after a prominent black agriculturist, scientist, and inventor, born during the Civil War. (US Office of War Information)

As for Knudsen, despite battling criticisms and frustrating strike actions, by the time America officially went to war on 8th December 1941, I think we can say that he could not have expended any more effort in the name of preparing his adopted country.

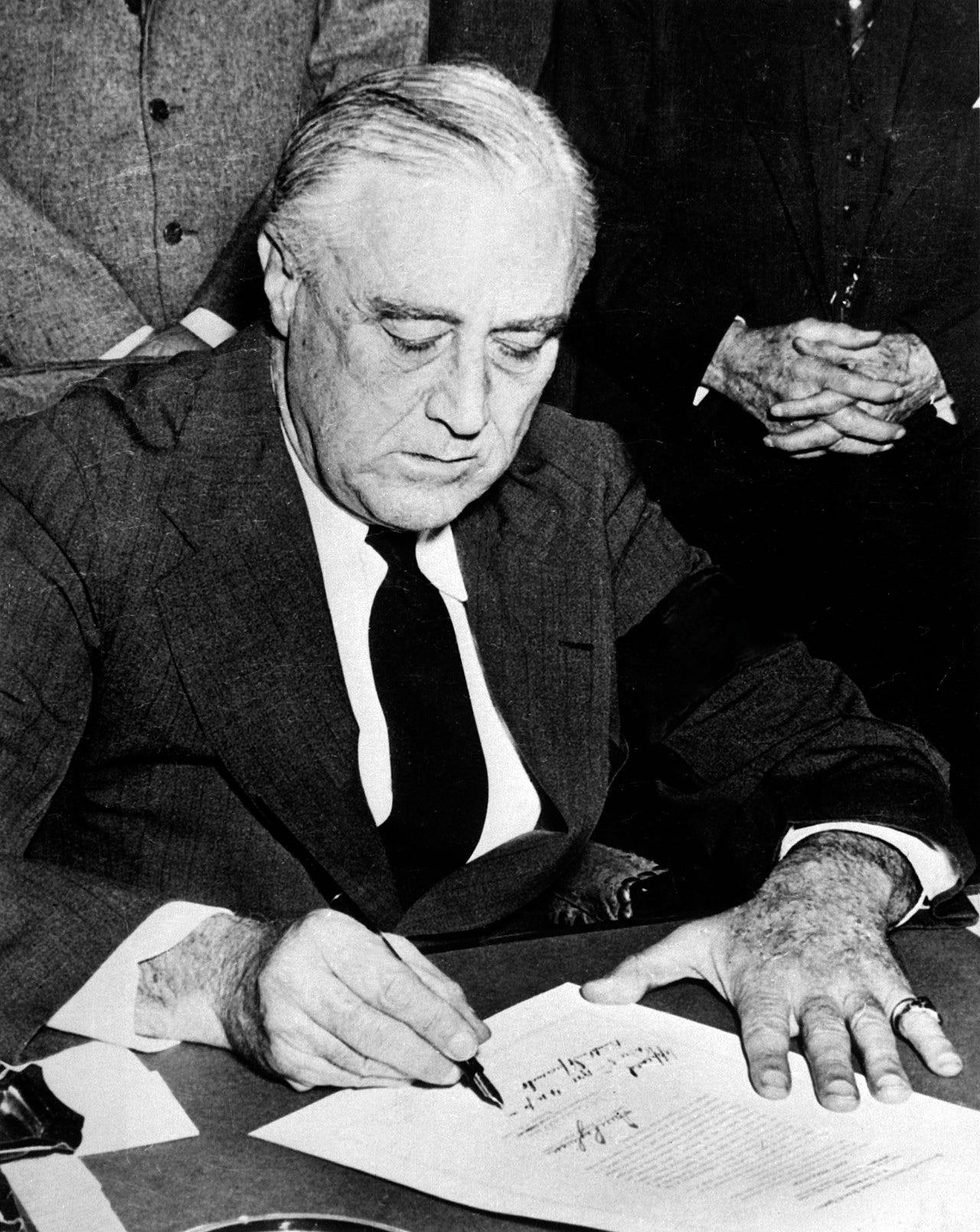

FDR Signs the declaration of war against Japan on 8th December 1941. (NARA)

If you want to know the full story of how America mobilised industry for war, you can do no better than read Freedom’s Forge by Arthur Herman, which inspired someone to come up with the concept of War Factories in the first place. All my stats came from his book unless otherwise stated.

Also, huge thanks to Allen Packwood, Director of the Churchill Archive at Churchill College Cambridge, for rushing to my aid with this. The contents of the telegram comes from volume one of William Kimber’s record of the correspondence between Churchill and FDR.

Interesting piece. A production and economic juggernaut to this day. Alleged Nazi sympathizer not mentioned, by design, I assume? Just wondering any chance you could do a piece on General Slim (did I spell the name correctly), who read was probably the best Brit General in WWII.

Kaiser's health insurance program survived his shipyards and is aptly named Kaiser Permanente.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/economics/economics-magazines/kaiser-permanente#:~:text=HISTORY,building%20the%20Los%20Angeles%20Aqueduct.