FREE ARTICLE: Meet Hirfa

One pissed-off Bedouin woman collides with one lazy husband

I travel and work in Jordan extensively, and it is one of my favourite countries on earth. Without a doubt, much of the appeal is my amazing, adopted Bedouin family. Forget Lawrence of Arabia and the depiction of Howeitat leader Auda abu Tayi as a money grabbing bastard, only in the Arab Revolt for the gold. He was a piece of work, absolutely. I’ll tell you more one day, but that portrayal was too much and his family sued the film makers for making him look greedy and self-interested. My own experience is to think of the Bedouin as like a mafia-esque extended family of wheeler dealers, but without all the killing. Cross one, and your name is mud throughout. But the Bedouin will also give you the last of anything they have and be offended if you don’t take it. If one adopts you, you belong to them all. They will fiercely protect you, (to the tune of chasing you around the desert with a Spiderman duvet if you look ill).

To tell the first-hand story of a Bedouin woman living in the Arabian desert 150 years ago, we will need a rich white man. But I think we should cut this one, Charles Doughty, a break. He did something new for the time, after travelling extensively in Arabia in the mid-1870s. He produced a very successful two volume travel book describing (laboriously) everything he saw. A lot of it is what you’d expect; scenery, buildings, Petra, local politics. But with his completely self indulgent word count, he gave us something else. He did us future historians a great service in recording glimpses of women and their everyday lives.

My favourite example of this is the story of Hirfa. Buckle up. If you’re expecting the trope of a down-trodden, silent wife with no agency, walking in the shadow of her Arab husband, shit’s about to get real. What we have left of this young Bedouin woman, thanks to Doughty, is so human, and so relatable that I wanted to share it with you.

Thank you to my amazing friend Tim Catherall for imagining what Hirfa might have looked like! As you read on you’ll see how on point the facial expression is…

So in the 1870s Doughty was wandering in Arabia. He had come south from Damascus, and he was following the procession of the Haj; the annual Islamic pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca. On his way, as he approached the Wadi Rum area of what is now Jordan, he met a worldly Bedouin sheikh of the Fukara tribe named Zeyd.

Doughty in his Arab garb. Lawrence didn’t invent the wheel.

Doughty described him as so dark he was almost black. This made Zeyd interesting, because skin this dark was a rarity among these Arabs, and not valued highly. ‘They think it resembles the ignoble blood of slave races, and therefore even crisp and ringed hair is a deformity in their eyes.’ He was of average height and somewhere in middle age. Oh, and wiry; ‘with a hunger-bitten stern visage.’ Fuelled by coffee and tobacco, (like almost every Bedouin man I’ve met) Zeyd apparently had the deepest voice that Doughty had ever heard.

The Englishman didn’t dislike him as such, but Zeyd wasn’t the nicest of men. He was not uncivil, but his one notable flaw was a complete lack of hospitality. You can’t sit down in southern Jordan without someone pouring you tea. For a man of his standing to go as far as to hide when he saw acquaintances coming to avoid this sort of thing was highly unusual, but Doughty readily admitted that his friendship was ‘true in the main, and he was not to be feared as an enemy.’

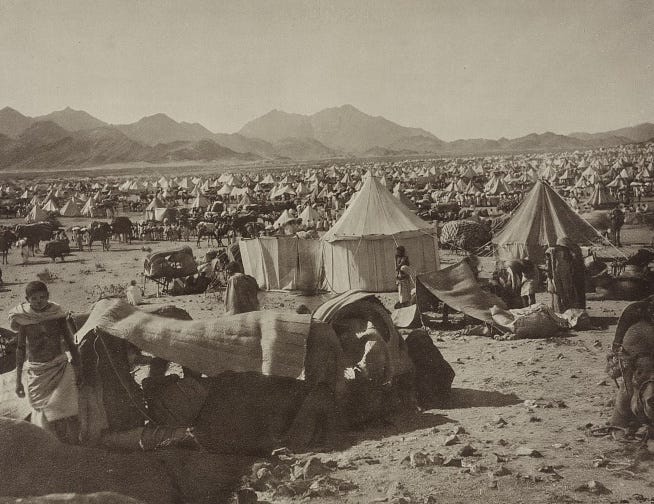

Doughty met Hirfa when he was travelling to and from Mecca to witness the Hajj. This photo was taken a decade or so after he made his trip. (Library of Congress)

Some months later, reunited with Zeyd on his return journey and leaving the Haj caravan, Doughty was taken to a Bedouin encampment to the southeast of Tabuk, which now sits in the far north of Saudi Arabia.

All of this explains how Charles Doughty came to meet Zeyd’s wife, Hirfa. On finding the camp, high up on rocky ground, he was surprised to be led into the women’s quarters. Here he was introduced to her. ‘See thou take good care him,’ Zeyd ordered.

Hirfa was about 20, by Doughty’s estimation, with a still-childish face. She was quite short, and ‘thick’ in stature, but she was attractive. One quality he singled out was her laugh, which was merry and usually at the expense of Zeyd. She’d sigh at the end and say: ‘The woman sighs who has an ill husband.’ She was an orphan, but of high status because she had subsequently been adopted by another Sheikh who had taken her on in order to gain the camels she had inherited. (Camels are up there with tobacco and coffee for the Bedouin. They’re the equivalent of a sports car. Most of the time, a man has to settle for how many goats he can accumulate).

Doughty keenly recorded his observations about the dynamic between the two. Breaking camp to move on appeared to be almost exclusively the responsibility of the women: ‘Sheikly husbands help not their feeble housewives to truss the baggage; it were an indignity even in the women’s eyes.’ The men sat about drinking coffee until they were done. ‘Only the herdsman helps Hirfa to charge them.’ Though this time, Zeyd did not get away with it, for the loads were to heavy for his wife to deal with. ‘Zeyd… did it grudgingly, murmuring, “Was a Sheikh a porter to bear burdens?” Hirfa tolerated the way things worked, but not without both complaining and mocking her idle husband. Doughty watched them have regular spats. Everything would be fine, then they would spit insults at each other and the mood would change.

Zeyd did not have a good track record with wives. The first, who had given him at least one son, had run away to her mother’s tribe. This was the ultimate put down. For a Bedouin man to have it publicly known that he could not take care of his wife was a complete humiliation. She was apparently a stunner, with eyes as big as eggs. Whilst Doughty was travelling with Zeyd and his family, the latter heard that said mother’s tribe was nearby. Zeyd rode over to the encampment and whatever charm he turned on, whatever promises he made, he convinced the first wife to return. This is all fine, a Bedouin man can have four wives. If he is prepared to treat them right.

Doughty’s opinion was that her pretty eyes were about the only thing the woman had going for her. Hirfa was even less impressed. She had opinions. At this point, she had been married to Zeyd for two years and to compound her dissatisfaction with him in general, he had yet to give her any children. She’d just grown weary of the whole setup. She was unsurprisingly jealous when her rival returned and the woman compounded the insult by refusing to pitch her tent anywhere near her.

And this is where Zeyd’s troubles began.

If this was how the game was to be played, then Hirfa wanted in on the action. She set her sights on a handsome young herdsman and whenever Zeyd was away, she’d openly flirt with him. The poor man must have been terrified, for this was the wife of his Sheikh. Zeyd’s response was to get out the rod and beat her.

What happened next was told over campfires and coffee with much laughter throughout the region. One day when they arrived at a new campsite, Hirfa made a half-arsed effort putting up the tent, and then she left.

This was not unheard of. Zeyd was not the first failing Bedouin husband, and Hirfa was subjected to the usual response. A male relative arrived, went out into the desert and within an hour deposited her back at the tent in a miserable mood. At least she would have appreciated Zeyd’s punishment, which was to spend all of the following nights with wife number one. She was spared, but still dissatisfied. Soon, she walked into the desert again.

This time she found some of her mother’s kin nearby and took up residence. At this point, dragging your wife home from the arms of her family when you’ve clearly irked her enough that she doesn’t want to be anywhere near you was frowned upon. She would have to come willingly.

Zeyd responded by sulking. He sat outside his empty tent, morose, then took naps, until Doughty convinced him to go and find coffee. Doughty soon found himself in the thick of this domestic drama. ‘Zeyd complained in his great… voice, that he had a household no longer, unless [Doughty] would fetch Hirfa home.’ He agreed to do it. He found her looking slightly embarrassed among a gaggle of her late mother’s friends who were thrilled to be in the thick of such gossip-worthy events. They said they’d stop her leaving, so did their men, who said they’d marry Hirfa themselves before they let Zeyd have her back.

In the end, Hirfa had a lengthy chat with Doughty and agreed to return home. Enough bribery in the form of tobacco was handed out to pacify the relatives and off they went. Normality resumed. Fetching, cooking, carrying, cleaning for Zeyd, but with notable variation. Doughty recorded that Zeyd had the sense to employ a ‘little Bedouin maid’ to help Hirfa. He continued to sulk, but kept his distance, returning much of the time late into the evening when it was time to go to bed.

Doughty spent a lot of time drinking tea with Hirfa. Zeyd wouldn’t let him wander off lest some less kindly tribesman murder him. The Bedouin take their black sage infused tea with equal parts water and sugar, and no milk, which amused the Englishman. One day he invited Hirfa to his quarters for his version, which much amused her. Why would he make tea for a woman? It was normal, he told her, to do something like this for a woman in England. ‘Ah! that we might be there among you!’ She quipped. Never one to pass up an opportunity to speak her mind, she addressed the men gathered nearby. See, she told Doughty, who they called Khalil, ‘these Beduw here are good for nothing… They are wild beasts; today they beat and tomorrow they abandon the harem: the woman is born to labour and suffering, and in the sorrow of her heart.’ For good measure, she added, this was supposed to be endured in silence. ‘The men sitting at the hearths laughed when Hirfa preached. She cried peevishly again, “Yes, laugh loud you wild beasts! Khalil, the Beduw are heathens!” She said all of this with a smile on her face, but Doughty noticed that when she turned away, her expression was tinged with sadness.

Hirfa did have her interests. Medicine for the Bedouin was once again a woman’s role. Hirfa was reputed to be skilled in the art of leechcraft, but she was delighted by Doughty’s western supplies. ‘One day calling her gossips together, they sat down before me to see my medicine-box opened. The bewildered harem took my foreign drugs in their hands, one by one; and, smelling to them, they wavered their heads with a wifely gravity… But what was their wonder to see me make an effervescing drink! Hirfa oftentimes entreated me to show her gossips this marvellous feat of “boiling water without fire.”’

When Zeyd hung about the tent, Hirfa remained hidden. In any given Bedouin set up, there is a partition to the women’s side. Its usually neck height at most, but means that for discreet moments, such as sleeping and cooking, the screen affords privacy. She would hide on her side.

One day, one of the cousins made fun of her. ‘Hirfa ho! Hirfa, sittest thou silent behind the curtain, and have not the harem a tongue? Stand up there and let that little face of thine be seen above the cloth, before the company.’ They asked if she still disliked her husband and berated her for leaving him. One particularly odious man asked Doughty to confirm that if his women were worth 60 camels, Hirfa was not worth five. Was there anything worse than an irksome woman? ‘Hirfa, showing herself with a little pouting look, said she would not suffer these comparisons.’ She told Doughty he need not comment, and when Zeyd offered her to his English visitor so he could be rid of her, Doughty politely declined to take another man’s wife. On another occasion, Hirfa asked him to buy some camels and take her, so that she might live a happy life in a different manner. She was sure Zeyd would consent for her to leave. I have to think she was only half joking.

What I like most about Hirfa is that opposition did not make her stop telling everyone what she thought. She didn’t stop talking. I hope she continued to speak her mind. I hope that Zeyd learned his lesson, and if not, I hope she left for good, maybe with the terrified herdsman. Either way, I hope she got the kids she so badly wanted. Thanks, Hirfa, for reminding us that women in history were definitely not silent, even if it’s harder to find their voices, and that they did not simply accept what was thrown at them. And thanks, Mr. Doughty, despite your weird writing style. For not being a mediocre Victorian dude and writing them out of your manuscript as superfluous, whether it was by accident or design, we appreciate it.

The book I referred to by Charles Doughty is Travels in Arabia Deserta. It was first published in 1888, but the version I own is an expanded reprint from 1923.

The story of Hirfa is a lovely one, one that could be told by a lady of today, i hope she found the contentment & happiness she desired.

An inspirational read great story telling