If you’re a WW2 nerd, there is no way you’ve got this far without noticing that some people place the beginning of the whole sorry mess not in 1939, but two years prior. You’ve probably caught on to the fact that it’s because of China and Japan, but that might be as much as you’ve absorbed. Getting to grips with what happened in the Far East in 1937 to warrant this school of thought has been a rabbit hole for me for the last few months. There are whole books on this, but this should suffice to start wrapping your head around it. There’s recommended reading at the other end…

The first recorded battle between China and Japan is thought to have taken place in the 7th Century. They’re neighbours, it’s not surprising. The dynamic of their potentially violent relations by the eve of the Second World War, however, went back to the 1850s. On the eve of the Second World War, don’t think of China as it is now. Think more along the lines of a centralised government with a shaky hold on power, communists knocking on the door, and a number of warlords ruling over various bits of territory.

Chiang Kai-Shek was the Chinese Republican leader attempting to simultaneously straighten out chaos and modernise China prior to the Second World War. (Wikipedia)

The hundred years prior to 1945 are referred to as the Century of Humiliation. As the 300-year-old Qing dynasty fell apart in the mid-nineteenth century, the First and Second Opium Wars were chastening for China. Then there were annexations and incursions, the defeats stretched far beyond the field of battle and into that of diplomacy.

Whilst China was in free fall, Japan was on the rise. To ward off probes from western powers, isolationist policies were abandoned and the country entered the modern world with systematic force. In thirty years government, industry, the army were all overhauled. Japan looked outwards, as well as within. China was constantly in the line of fire. Korea had been wrestled from Chinese possession, a sizeable dent was made in the Chinese Navy, the First Sino-Japanese War was an overwhelming victory for the latter, and Japanese troops had smashed Russia on Chinese soil in 1905, sounding a klaxon worldwide as to her territorial ambitions. In 1915, China was so weak, that the Emperor of Japan issued a list of ‘Twenty-One Demands’ that made the ultimatum from Austria to Serbia that ignited the First World War six months earlier look tame. Japanese forces then landed on neutral, China soil to wage war against Germany at Tsingtao. Attitudes softened in the 1920s, but then China’s nationalist government took power in 1925. Republican Chinese ideology clashed badly with Japanese imperialism. Sooner or later, this complete discord in thinking, and how the two leaderships were approaching their respective futures in Asia and beyond was going to lead to a showdown.

Setting yourself up to compete on the world stage is one ambition, that didn’t make Japan unique or any worse than any other Imperial nation. But the link between that and the absolute fanaticism that drove Japanese commanders and their forces until defeat in 1945 is the bit that blows my mind. Defeat by one army over another is one thing. Widespread, depraved atrocities are another altogether. For me, I feel like trying to understand what happened in Asia and the Pacific requires a concerted effort to learn how Japanese people thought, acted and responded to events. Every cultural point of reference, tradition, perspective, is so different to what I am used to. I live next to France. There’s familiarity. I feel like I know what makes the French tick, I’ve studied enough, seen enough and been there enough to feel comfortable saying that. I cannot say that about Japan on the other side of the planet. Not yet, anyway.

I suppose if you think about it from Japan’s point of view, the whole concept of reform and modernisation had stemmed from the broad threat of western imperialism. So then it shouldn’t be surprising that this manifested itself from the 1850s onwards in a desire to be strong enough to resist this threat. They fashionably found some Germans to come and influence their ideas in the years to come, not the only country to do this, but at some point, military/naval power became tantamount to an obsession. It started off with secret societies and paramilitary groups and then went mainstream, not just a bit, but widely. There were a litany of contributing factors, but what is particularly interesting to me is that there was also a fair bit of taking traditional ideas and adapting them to this new, westernised approach. They were reformatting them for modern use in a country that was very much trying to transplant in something that looked like a familiar European aristocracy as opposed to leaning on the shape of the societies that these ideas were inherited from.

Hirohito looked unassuming. He was also a constitutional monarch, not an autocrat, but the cultural importance of the Emperor was massive. (Wikipedia)

An assassination attempt on the Emperor in 1932 led to a surge in patriotism, and jingoistic rhetoric was even brought into schools. A lot of this might sound familiar (Kipling, anyone), but the mood in Japan ended up developing a malevolence in some quarters that made it distinctive. There were straightforward attempts at a coup to replace the government with a military dictatorship. But the army did not stop there, and it impacted people beyond Japan. For example, also in 1932, you have the Shanghai Incident. This was an undeclared war, in which Japanese forces spent three months bashing away at an area around the city. This was a Japanese Army intentionally going rogue. It would not be the last time.

There was no democratic decision for Japan to go to war, but what could Tokyo do about it? The way Japanese politics was arranged, no Cabinet could survive without the complicity of both a naval and an army representative. Another coup attempt followed, secret executions, but the government was pressed into accepting demands, notably on military spending, because it would fall apart if the army or the navy walked away from the Cabinet. The Imperial Navy was belligerent too, with a righteous cause. The 1930 London Naval Treaty sought to dictate how far the Japanese navy was allowed to expand based on a comparison with Britain and the United States. This was just one thing that helped the Japanese media imbue the public with the idea that rival powers were attempting to strangle Japan, conspiring to hold back her progress. Even the general public appeared to be infected with a ‘war fever.’ A common feeling grew that it was Japan against the world.

By 1937, nearly half of Japan’s national budget every year was spent on the military. Dangerously, it had now outgrown the resources Japan and her territories had to offer. Without conquest, enough resources like oil and rubber were not available. There were other reasons for expansion. At the beginning of the 1930s, Manchuria was viewed as a necessary buffer to protect Japan from western imperialism. In 1931, men from the Kwangtung Army, Japanese forces based in occupied Korea, waltzed across the border, bombed a railway line and began harassing local officials.

This is known as the Mukden Incident.

This photo claims the show the damage done by the Japanese bomb that was blamed on the Chinese. If it is, to me it looks like a very small hole to use as an excuse to invade Manchuria.

You’ll notice some distinct f*ckery going on here with the terminology. ‘Incident’ was employed as a way of toning down the optics on an outright, blackguardly act of aggression. The Japanese used it enough in this period to make the principle of that redundant. If you add enough of them up, everyone is suspicious of you whatever you call it.

For the victims in this case, China, to embark on a war with the Japanese in response would have been suicidal. The area that subsequently fell under occupation was nearly four times the size of Britain, but the occupation of Manchuria went unchallenged, in spite of significant atrocities carried out on the local population. A dangerous precedent had been set by now: An ‘incident’ occurred at Japanese instigation. China opted for outwardly placating her neighbour and enduring humiliating concessions in territory. In future, Japan would expect the same again.

Following Mukden amidst widespread, devastating poverty and internal squabbling with a communist contingent that featured a certain man name Mao, the Chinese government did attempt to make preparations to defend the country. With an inevitable war against Japan in mind, in 1932 surveys were made to assess the country’s industrial potential. As for the army, successive German officers arrived from 1934 to help create a small but professional republican force. All of this was paddling against an overwhelming current. China lacked the resources to compete with Japanese spending.

In the meantime, for Japan tensions also rose with the Soviet Union. Believing that war was inevitable, the Japanese government wanted China dealt with; they wanted no unpredictable, weaker influences left lurking in what could be an important battleground against the might of Stalin’s forces. Every spat or flare up in China, Japan banked as an excuse to increase their burgeoning presence in the north. Isolated scraps and acts of Chinese opposition, often along the railway connecting Tianjin and Beijing, were branded as a united conspiracy against Japan. Relations deteriorated. War became more and more likely.

Ignition

The conflict that began in 1937 signified the beginning of the end of China’s misery on the international stage. Not, however, before the bloodiest finale imaginable. Fighting the Axis powers, by 1945 China had paid for this rebirth with some fourteen million dead, up to 80 million refugees and the destruction of almost everything the country had done to modernise itself at the beginning of the twentieth century. Today’s China was born from the ashes of armageddon, having been downtrodden and exploited by members of the international community for decades.

Spanning the Yongding, the Marco Polo Bridge, weighed down with carved stone lions and admired by the famous explorer in the Middle Ages, was about the only thing of note at Wanping. A hamlet on the railway line just outside Beijing, international agreements permitted the Japanese North China Garrison Army to be in this area. In July 1937, they sat eyeballing the Chinese 29th Army, and on 7th, gunfire erupted.

The Marco Polo Bridge (you guessed it,) Incident, began because the Japanese lost a soldier. They demanded to enter Wanping and look for him, and the Chinese said no. Despite the fact that he’d then turned up claiming he had an upset stomach and ran off looking for an undignified moment of privacy, Japanese troops continued to mobilise and then, someone fired a shot. In the end, who was responsible didn’t matter. Almost immediately, it was apparent that this episode would not be contained locally. It was not going to be another storm in a teacup: a flurry of violence, demands by Japan, the usual stand down and concessions made by the Chinese; then the resumption of an uneasy truce. For once, the Chinese put their collective foot down.

As commanders from both sides at Wanping discussed a ceasefire, in his capital at Nanking, bitterly referring to the Japanese as ‘dwarf bandits,’ the Chinese Premier, Chiang Kai-shek pondered whether this was the beginning of something big. If it was, it wasn’t simply a case of giving up more of Manchuria this time, far flung and easy to forget about; easy to reason away. At risk now? How about the ancient, iconic city of Beijing. At that point, what was to stop the Japanese from overrunning the country entirely?

Chiang also knew, however, that there would be no allies if he chose to make a stand. Nazi Germany, Stalin’s Soviet Union and Mussolini’s Italy were all more interested in their stakes in the burgeoning Spanish Civil War on their European doorstep. The likelihood of Britain, France or the United States involving themselves in an Asian war was non-existent. If Chiang was going to oppose Japan, it would have to be alone. A one-sided stage in Asia was set to deliver a crushing defeat on the Chinese. And yet giving an easy target like China a slap was one thing. The knock on effect that might have on Japan’s ability to fight the USSR in the region if it became necessary, was entirely another.

So there were considerations that might have given Japan pause for thought, but when China sent troops north to oppose them, the Kwantung Army responded. Outnumbered by the enemy, Beijing fell in two days, Tianjin after four. In the meantime, Chiang had turned desperately to the Communists. It was a tense combination. The nationalists didn’t trust the communist forces and as for the communists, they had been mercilessly persecuted by Chiang and his government. In the end, desperation won out and an uneasy alliance ensued. Chiang permitted the formation of the Chinese Red Army and in a significant ideological sacrifice, Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, agreed to unite with the nationalists and help fight off the overwhelming strength of Imperial Japan.

Chiang decided to be proactive. He would never have committed his best troops to defend the north, bandit country ruled by unpredictable warlords over which he only had a tenuous hold. The port of Shanghai was different. Shanghai was self preservation. The first step to protecting the rest of China was to attempt to disrupt Japanese forces from reaching the mainland altogether. The effort was understandable, the results, sadly predictable. Japanese troops began landing. The population fled in terror as 32 imperial warships steamed into the harbour.

This incredibly famous photo by H.S. Wong is of a child in the ruins of a train station in Shanghai. It was taken in August 1937. The child’s mother was said to be lying dead a few feet away. The photograph was seen by hundreds of millions people across the world and caused outrage. At the time, and since, Japanese nationalists have claimed that the image was staged to stoke American opinion against Japan. More footage shows a man said to be (by Wong) the child’s father coming to rescue it, (the gender is unknown) and the child receiving first aid on a stretcher.

By the end of October, vibrant Shanghai was holding out as a smoking ruin and the Japanese held a port. In the west, nobody was moved particularly to intervene, not even in their own economic interests.

Nanking, the Chinese capital, sat 190 miles northwest of Shanghai and looked completely different. It was of huge cultural significance as a former imperial capital, and was packed with impressive architecture and western, tree-lined boulevards.

This image shows the university at Nanking. In the midst of huge overhaul, the city was a burgeoning symbol of every aspect of modernisation envisaged for the country by the nationalist government. To conquer it would be an international coup for the Japanese. (Library of Congress)

But the Japanese would do more than just conquer it, and the impact of what was about to happen at Nanking stretched far beyond Asia.

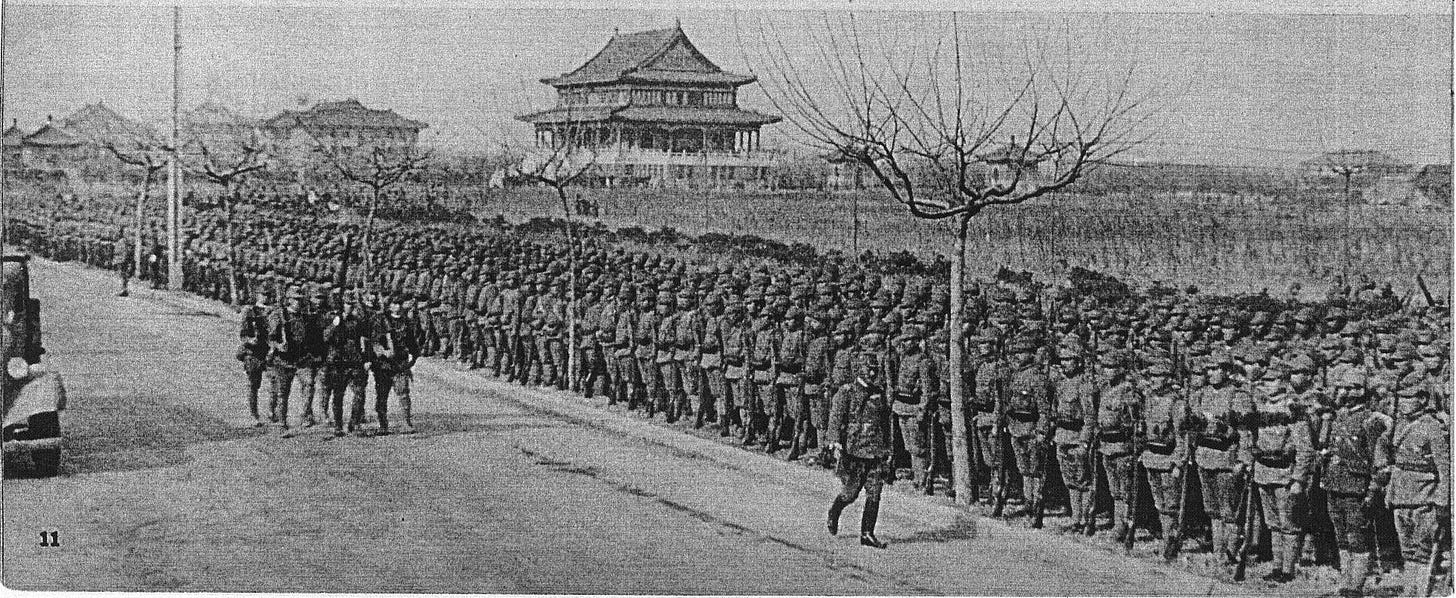

Japanese soldiers arranged in Nanking.

I’m still learning all of this. I can think of two books and either one of them would be great if you want to follow what happened next and get the full picture. Rana Mitter’s has different titles on either side of the Atlantic I think, but is excellent, that or Tower of Skulls, by the lovely Rich Frank. Both have contributed to my podcast, History Hack, in the past, speaking about aspects of Asia and the Pacific in the Second World War.

Thanks to Josh Provan, who wrote the excellent Wild East about Britain and Japan in the mid-19th century.

Great article. One of the books I’m currently reading is Rising Sun by John Toland - quite eye opening particularly regarding the negotiations between Japan and the US before Pearl Harbor

Very interesting. I’ve read Rana Mitter’s China’s War with Japan 1937 - 1945 (Penguin Books 2014), good book.