FREE ARTICLE: Ben-Hur: Again

Breathing new life into an Easter tradition

One thing that is almost as nailed on as my inability to avoid chocolate this weekend, more so even, is that the 50s version of Ben Hur will be on television for half the day. For those in Britain, 12:05pm, Channel 4. For those of you that have seen it annually to the point of saturation, and skate on past it because you think that the story of a Jewish nobleman constantly running into Jesus has nothing more to offer you, I’m going to attempt to tell you some things you didn’t know…

THE IDEA: The guy who thought it up was a Civil War general and this may have impacted the story.

Lewis Wallace was born and raised in Indiana. Already an officer with combat experience, he was in his mid-thirties when the Civil War began, and set off commanding the 11th Indiana Infantry Regiment. Arguably of all his experiences, it was the Battle of Shiloh, which took place in Tennessee a couple of day’s after Wallace’s 35th birthday in the spring of 1862, that left the biggest impression on him. The Union forces won, but at a huge cost. In the aftermath of the battle, a controversy emerged that threatened his career. The public were dismayed by the casualty figures, and naturally, politicians panicked. Lincoln’s government asked for an explanation.

Lew Wallace

It’s at this point that generals generally end up scrabbling to point the finger at someone else’s incompetence. These are highly competitive men who have fought their way to the top of their field. Unfortunately for Lew Wallace, his commander, Ulysses S, Grant, who was also being accused of everything from shoddy defences to being shit-face drunk, decided with others that Wallace had failed to follow orders and that he had dithered so badly in arriving for the battle that he almost handed victory to the Confederates. He was removed and would not command on active duty again until 1864.

Wallace’s reputation as a solider was damaged, and he would spend the rest of his life trying to counter public opinion and challenge the accusations levelled at him. ‘Shiloh and its slanders! Will the world ever acquit me of them?’ He once complained. ‘If I were guilty I would not feel them as keenly.’ Keep this in mind. Because it comes up again in connection with Ben Hur.

Lew Wallace had the interesting distinction of serving on the commission for the trials of the men who conspired to assassinate President Lincoln. He resigned from the army after the war, and returned to Indiana to follow both his father and his grandfather into high-level politics. In his spare time, being one of those annoying people who is good at everything, he was an artist and an author with a couple of novels to his name. Wallace spent the years 1878-1881 as Governor of New Mexico, and whilst the entertaining aspect of his day job was trying to run Billy the Kid to ground and withdraw him from raising hell on his patch, he was putting the finishing touches to a book: Ben-Hur, A Tale of the Christ.

THE BOOK: Is one of the biggest sellers in American history,

Ben-Hur set Wallace up for life. It was published in 1880, and after a slow start, it became a massive, sustained smash hit. For the next 100 years, it was never out of print. By 1912, a million copies had been sold in more than 35 languages, and Wallace had overtaken the previous bestseller of the century, Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. The only book that outsold him was the bible, and it would remain the biggest selling novel in America until Gone With the Wind came along in 1936.

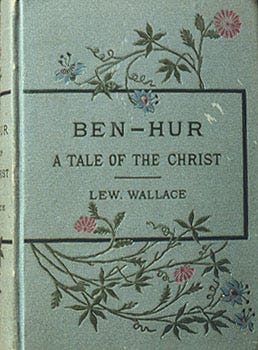

A first edition cover. People whined about the design, not least Wallace’s wife, Susan. Flowers were far too frivolous for the subject matter, apparently. It was actually adhering to a series that already existed and that the book was a part of, but to get their own back on her, the next two bindings were done in very, very dull, plain cloth.

But how did Wallace go about writing it?

The version that you’d recognise in the film isn’t how it was originally envisaged. He initially started work in 1873 on a magazine series that was all going to be through the eyes of the three wise men. He wasn’t a religious zealot; not at all, actually. He admitted he was embarrassed about how uninformed he was about Christianity. Far from preaching his idea of it to people using his book, writing it actually helped Wallace form what his own ideas about religion actually were.

As he worked on his idea, Wallace went from the viewpoint of the biblical Magi, to developing a story about Christ, and then created his own character, a wronged man whose reputation is tarnished after an accident at the centre of a story, running parallel to the life of Christ.

Shades of Shiloh? There’s a historian out there that thinks Wallace put a lot of himself out there when it came to plot arc that sees Judah Ben-Hur falling from grace. There’s even a suggestion that the chariot race between Messala and Judah is based on a horse race between Wallace and Grant following Shiloh.

Wallace wrote the book all over the place, whenever he had time, but there is a famous beech tree near his old home that is called ‘the Ben-Hur beech’ where he used to settle down in summer to work. He was all about the research, too. He spent days in the Library of Congress looking at maps, and also did reading in Boston and New York. On his trips he put together painstaking detail about the ancient world and how people lived, especially the history of Rome. He also studied the bible extensively.

He spoke about his obsessive background work in his autobiography:

‘I wrote with a chart always before my eyes, a German publication showing the towns and villages, all sacred places, the heights, the depressions, the passes, trails, and distances.’

It took trips to both Washington and Boston, apparently, just to obtain the exact measurements of a Roman oar for when he was writing about the slave galley. Proudly, when he finally got to visit the Holy Land after the book was released, Wallace claimed that he had been unable to find ‘any reason for making a single change in the text of the book.’ Not bad for a man who didn’t have wikipedia at his fingertips.

He was also pushing literary boundaries for the time. An important thing to consider is that in 1880, you were a brave, brave man if you were going to fictionalise the crucifixion and death of Christ for what was essentially an adventure novel. Wallace’s publisher was a wary, but apparently the quality of his work won out. I think from what I’ve seen, he was helped by the very genuine, open way in which he would discuss his own beliefs and his motivations. The quotes available online don’t read as blasphemous, or pretentious, just seemingly honest, uncritical or judgemental and meaning no disrespect.

Critics actually bemoaned the actual writing more than the content, and hated seeing it on lists of famed American literature. This was pulp fiction, not high brow writing. But it was entertaining, and eventually millions of people read it. A scholar has suggested that both north and south were so exhausted by war and reconstruction, and division, that an idea as simple as a Christian novel with a convincing hero was just what America needed at the time. Among the people singing his praises were highly placed religious fans of the book, and none other than President Ulysses S Grant himself, and so opposition was less than might have been feared. If the church didn’t hate it, then why not?

THE FILM: Finding a new way to employ an eminently bankable idea.

Everyone loves money, and Ben-Hur generated it. Unsurprisingly, there were other dramatisations prior to 1959. A stage version opened on Broadway in 1901. It drew whole new, Christian audiences into the theatre, and at one point was selling 25,000 tickets a week. Churchgoers who usually shunned the stage were desperate to see it. When It came to the chariot race, there were real horses and chariots moving on treadmills as the backdrop rotated behind them. Apparently, when he saw it, Wallace was stunned that what he was seeing had come out of his own head. No expense was spared in shipping thirty tons of equipment and staging to London, either, including fountains and palm trees. The stage had to be reinforced, and a Roman galley was sunk live. (Let’s not talk about the 2017 Korean musical version)

Wallace died in 1905 and never saw a film adaptation. On screen, since 1907, there have been five sanctioned adaptations and a mini-series, but the one that matters is the 1959 epic. So what can I tell you that you might not know?

Firstly, the whole future of MGM was in financial turmoil until they decided to try and get some of the sandal and sword action that had been so profitable for Paramount with The Ten Commandments. In a way, perhaps it saved them. But notice if you’re watching the original version, that the famous, roaring MGM lion at the beginning, he doesn’t roar. For the first time, he was pictured looking very docile. This was because the film goes straight into the birth of Jesus and it was considered unseemly to have him making a row before such an auspicious event. Those religious worries about depicting Christ? They still existed in the 1950s, but we’ll get to that.

Nice kitty. (MGM)

What about casting? Have you noticed that the dastardly Romans are British, and the Jews are played by Americans? That was intentional. British bad guys are, after all, the best (RIP Alan Rickman) and it created a divide for the audience to identify between them. Hollywood was also extremely sensitive about its portrayal of Jews in this film. Don’t forget this is less than fifteen years after the world found out the extent of the Holocaust, and nobody wanted to offend the new state of Israel, either.

Charlton Heston as Judah Ben Hur (IMDB/MGM)

Charlton Heston made the film what it is, but Kirk Douglas came close to getting the role before MGM made their decision. Marlon Brando might have been Judah, too. Burt Lancaster said he turned it down because the script was dull, (problems with getting the script right rolled on for years) but my two favourites? Paul Newman said he turned it down because he didn’t have the legs for a tunic, and one of the other actors offered the role? Leslie Nielsen. Yes. You read that right.

Most people have spotted that you never see Jesus properly in the film. A shadow, a hand, no voice. Wallace had always said that this was his preference in a dramatisation, but also, Hollywood panicked at the reaction to giving Christ a face. In fact, you don’t properly see Claude Heater, the opera singer who played him, he doesn’t utter a word and he did not even get a credit. (There are clips of him singing on YouTube, if you want to see)

Claude Heater on set as Jesus with the film’s director, William Wyler. (MGM)

I kind of think this has held up over the time. It feels classy? Watching Mel Gibson have people beat the living snot out of Jim Caviezel’s face in Passion of the Christ didn’t make it any more impactful. However, what to do about the portrayal of Christ still gave the director, William Wyler, headaches:

‘I spent sleepless nights trying to find a way to deal with the figure of Christ. It was a frightening thing when all the great painters of twenty centuries have painted events you have to deal with, events in the life of the best-known man who ever lived. Everyone already has his own concept of him. I wanted to be reverent, and yet realistic. Crucifixion is a bloody, awful, horrible thing, and a man does not go through it with a benign expression on his face. I had to deal with that. It is a very challenging thing to do that and get no complaints from anybody.’

It was the most expensive film ever made, and the scale of it was enormous. an MGM casting office set up in Rome looked for 50,000 people to use as extras and for minor roles. (When you factor in that lots of these Italians didn’t have phones and rounding them up for any massed scene took days of wandering and word of mouth and added thousands to the production in wasted time there’s a comedy aspect to it). The actual cast size was 365, but about 40 were considered as main players. Wyler watched everyone like a hawk, missed nothing, with sometimes fun consequences. Remember the bit where a centurion stops Judah having water at Nazareth? The actor that did that tiny role, he threw a wobbly and asked for more money and so the First Assistant Director got rid of him. Reasonable. However, Wyler wanted that man so forcefully that he shut down production, at a cost of thousands of dollars, until someone went to Rome to get him back.

(IMDB/MGM)

So the most famous scene… In the original script, it constituted three words: The Chariot Race. It’s worth putting the film on again to watch it and consider the effort that went into it. Those scenes were years in the making and took thousands of people. The set was a work of art covering 18 acres, which made it the largest film set ever built at the time. $1 million dollars, a full year of 1,000 men digging out a quarry, huge paintings produced to used to convince the audience of more tiers and elaborate background. For the race, nobody was sure what an authentic surface might have been anyway, but when it came to it, authenticity took a back seat behind practicality. They attempted to lay a surface that could hold the weight of the chariots, but also one that wouldn’t hurt the horses who would have to run on it for long periods of time every day. This included robbing 40,000 tons of sand from mediterranean beaches.

An identical track was built next door both to train them and to work out camera shots, and in the meantime it took a year to plan the shoot. 78 horses were extensively trained, with an onsite vet and 20 stable boys to look after them. Charlton Heston was experienced with horses and he took to three hour chariot driving lessons quickly. Stephen Boyd, playing Massela, however, struggled and it took him a month to feel even competent, not confident. Stuntmen and even the stand-ins had to make 100 practice laps before filming, and MGM were so ready for carnage, that they prepared a staffed infirmary to deal with any injuries. Two doctors were ready and waiting with casualties. (There’s a rumour that someone died during filming, but it has never been substantiated)

By the time the second team created the one of the most unforgettable scenes in cinema history, the instructions in the script were 38 pages long. Put together over a period of three months, it required five weeks worth of filming and an overwhelming amount of editing all the way through. Wyler didn’t actually direct the chariot scenes, because they constituted a whole other production going on parallel to his principal photography. Andrew Martin and Yakima Canutt were in charge with a series of assistants, one of whom was Sergio Leone, Clint Eastwood’s best mate in the land of cowboy. They filmed the whole sequence with extras to form the basis of the nine minute scene, including 7,000 of them acting as the crowd and cheering them on. (There was so much work going for locals that when this portion of production ended and the jobs dried up, the local economy took a hit and people staged benign, stone throwing riots)

Once Martin and Canutt had the outline, they went to Wyler with where they thought close ups of Heston and Boyd should go. Then they brought in the lead actors. They had intended to film in spring, to make it easier for the horses, but the track surface held things up. When shooting finally began in summer, they strictly limited how many hours the horses spent on set owing to the heat. There were still a multitude of issues to be overcome. The horses out-accelerated the cars on which the cameras were mounted, and they couldn’t shoot long enough sequences before they were overtaken. The cameras had to be changed, but to get the shot now, the cars had to operate dangerously close to the horses. If they failed to turn in time, or anything went wrong with the car, there was risk of a deadly collision. Cameras were trampled. That scene where Judah’s chariot jumps over the wreckage of another? The horses were trained for the move, and a telephone pole was buried in the ground to force the chariot to jump. Joe Canutt, son of Yakima, did Heston’s most dangerous stunt work, and as he was filming this, he was thrown in the air and very nearly seriously injured. They kept footage of this as a long shot for the bit where you see Judah almost fall out of his chariot, before he manages to climb back in. Adding close ups of Heston climbing back in to make the scene.

No, no, and hell no. Lucky for Canutt, he just got a bump on the chin. He was expecting the chariot to leap, but not to take flight himself. Given how extensively Wyler tried to convey the danger of a chariot race (such as the quick death of one of the runners at the beginning) I think that everyone was probably thrilled when it worked out OK for Joe. (IMDB/MGM)

Speaking of accidents? The horrific fate of Messala? Stephen Boyd did almost all of his own stunts, apparently. A dummy was used for the scene where he's mown down and trampled, because nobody is that method unless they’re insane, but for the part where he is dragged, he was wearing steel armour under his costume.

This is one of those films where it’s never a waste of time to rewatch it. If you do, spare a thought for the extras in the leper colony. Apparently they spent a whole month on that in November 1958, miserably hanging round for days at a time in leprosy makeup. Because of the issues assembling his extras, once Wyler had them he would keep them at it as long as possible.

Is it worth reading the book? I think so. It’s a slow start, but there are some gems in it. Sometimes, with a 550 page novel you need to make hard choices on what you can include, and so you’ll find things that aren’t in the film like the bit where Judah fakes his own death and goes off to raise a rebel army to bash the Romans. The age of it means you can pick it up for free as an ebook in numerous places.

The quote from Wyler comes from Jan Herman’s 1997 book: A Talent for Trouble: The Life of Hollywood's Most Acclaimed Director, William Wyler.

Never knew there was a Korean musical version of Ben Hur. I am so going to look out for that. Great article Alex.

As I often say every day is a school day. I knew the basics about Wallace but not the details. There is a BBC radio adaptation of the book, quite good as I recall. I have not read the book however I did read Gone With the Wind many years ago, much better than the epic movie. Great article Alex.