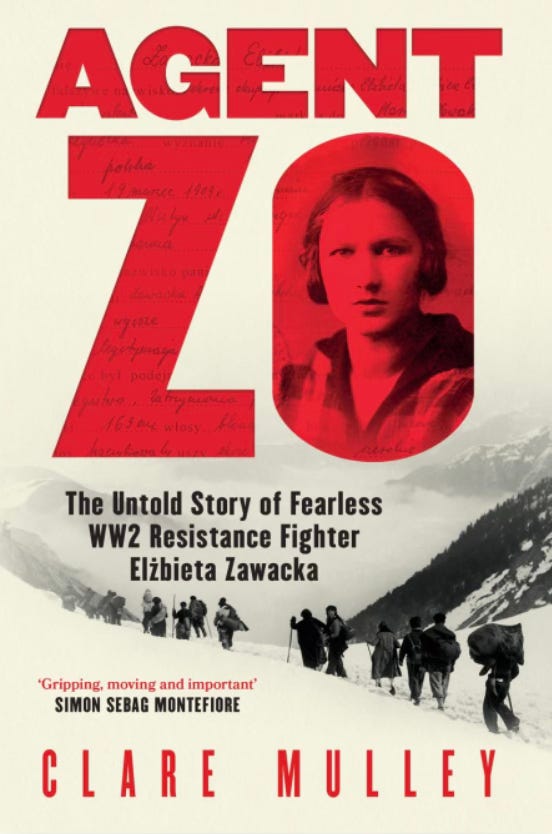

FREE BOOK FOCUS: The Awesomeness of Agent Zo

Only a legend parachutes into a war zone in a silk dress

So this is something else I thought I’d try. My friend Clare Mulley’s outstanding new book is released today, and she’s kindly given me permission to pick bits and use them to write an article about a very special woman.

We hear a lot about “secret” and “untold” history these days. It’s not every time that an author can proudly hold their head up and know that there isn’t at least a whiff of PR knobbery in it. Clare Mulley does not have that problem.

Background

So apparently she was only a courier. There’s nothing like someone’s unsolicited opinion on the internet. It might be better to wait until you’ve read the book if you’re in any doubt as to whether or not Elżbieta Zawacka deserves to be held aloft alongside the very finest operatives in the Second World War. Spoiler, she does.

She was born in Germany. Officially. When she was ten years old, the end of the First World War delivered her to Poland when the map was redrawn. She taught at secondary school level prior to the war, but was also heavily involved with Przysposobienie Wojskowe Kobiet, or Women’s Military Training. Having actively fought in the latter stages of the First World War, and against the Soviets into the twenties, those were disbanded. But there were still women who believed they should be entitled to defend their homeland alongside men, and they wanted to be prepared to do so.

Zo (centre) in PWK (Women’s Military Auxiliary) uniform (Elżbieta Zawacka Foundation, Toruń)

Elżbieta was 30 and an independent, single woman when the Germans and the Soviets involved Poland and carved it up between them in September and October 1939. This was only the beginning of her war. Poland had fallen, and she immediately signed up for Armed Resistance and became Zelma. Eventually, she shortened her nom de guerre, and with some necessary variants, became know as Zo.

By the end of 1940 Zo had relocated to Warsaw and become a courier. The bit of Clare’s book I want to zoom in on for you occurs in 1942…

Evading the Gestapo

It was dawn at the end of May, and Zo had made a stop at Sosnowiec, where her sister Klara lived. She was on a circuitous route to Warsaw from Berlin, with a suitcase lined with American dollars, but on arrival nobody was home. Eventually Zo pried the news from a neighbour that two days previously the Gestapo had seized her younger sister.

Zo had recruited Klara, moved her out of their parents home and to this apartment. Gut wrenching as this might have been, if they had come for her sister, who was lurking outside now waiting for her? The answer was one single Gestapo man, who whatever he was doing when she arrived late, was not keeping watch for Zo. Eventually she was yanked into a nearby apartment through the window by a friend who was clearly panicking and who revealed that it was not only had Klara and her flatmate Nina that been arrested. Saba, an intelligence officer from Kraków who was game for ferrying explosives about stealing identity documents from the occupying German authorities for agents and couriers had been intercepted by German police on the frontier, stripped naked but he Gestapo, beaten and tied to a bed frame as they tried to extract information from her. When they fixed electrodes to her body and began zapping her at high voltage, however, she caved. She had named several contacts, including Zo, and including Klara. Sitting in her friend’s apartment, Zo was the only one still free. In addition, the entire resistance was now under threat as the Gestapo combed through captured documents:

‘Large numbers of people had to hide, fast. Safe houses, contact points, weapons and information stashes all needed to be moved. And Zo still had to deliver her “unfortunate suitcase”, as she now regarded it, “lined with the many thousands of dollars desperately needed in Warsaw”. She knew that the Gestapo would have her name and a detailed physical description of her, most likely with a note that she would be carrying luggage, so her first priority was to stash the case. It was not yet dawn when she left Stasia's flat. She had had very little sleep over the last forty-eight hours but walked with a spring in her step, carrying the suitcase as lightly as possible as she headed to the left-luggage store at the station. As it was still so early, she felt she had both a duty and a realistic chance to pass on a warning before finding somewhere to hide the luggage ticket and lie low herself.

Sosnowiec station was always busy on weekday mornings when the occupying authorities brought in German-speaking women from across Silesia to clerk in the city's offices. Zo knew that several members of the Women's Military Service would be among them. Watching as first one train, then another discharged batches of secretaries, she finally spotted a contact and managed to warn her of the arrests. By chance, she then saw another friend on the concourse, one of the sisters who used to distribute the underground press. Giving a sign to let her know that she should not be approached, Zo whispered her the news as they passed. She had managed to send out at least a ripple of warnings.

Zo had now been at the station for some time without boarding a train and, although it was hard to be sure, she had the uncomfortable sensation of being watched. Turning quickly, she saw two men staring at her. Immediately she flushed, then cursed herself. Walking briskly out of the station, she leapt onto a tram as it was pulling away. To her disappointment, one of her shadows followed behind. It was still only eight in the morning when they both disembarked in nearby Katowice - he might as well have raised his hat to her.’

Having sensibly passed on her left luggage receipt, Zo hopped a train to Kraków. Where she was still being tailed. That night, she planned to take the last train to Warsaw. Her legs were shaking as she set out for the station, determined to get to the capital and inform resistance HQ. Travelling with fake German papers, she boarded a German carriage:

‘An army nurse was sleeping in one corner, her long uniform coat hanging temptingly on a hook behind her. Zo reached for it but, waking, the woman looked up at her reproachfully. At the same moment, a man in civilian clothes joined them in the carriage, his eyes fixed on Zo. Shaken, she walked through to the next compartment, took a seat, and turned her face to the window “In despair”’.

It was then that a complete miracle happened. Looking out across the dark platform, Zo saw Maria Wittek striding towards her platform. Finding some paper in her purse, Zo scribbled: Saba is leaking. Silesia has fallen. I am being watched. Zo.’

Maria passed, Zo recalled, then“turned away, as though she did not know me at all”. Maria now clutched the note in her hand.

Zo settled down at the train pulled out of Katowice, but no sooner had she begun to breathe a little easier, than her tail plonked himself down in her carriage, ‘with such a sense of entitlement that the other passengers automatically shuffled up.’ Zo was resigned. Jumping from the train in the midst of Silesia was, she believed, her best chance. ‘She had plenty of hiding places across the region, and she might even be able to organise help for Klara and the others.’

The problem was, that Zo was scared of heights. Added to that, there was the chance of being horribly injured in the fall, or hit by another train. The night drew on and she sat face to face with the man hunting her. She didn’t want to die, but was terrified that she would not endure torture without giving up her friends and family. At dawn, the train was approaching Warsaw. ‘Zo made her decision. If she could not jump now, she would take her own life by throwing herself under a locomotive at the terminus in the capital.’ She left everything she had with her in the compartment and made for the toilet:

‘Glancing back, she saw her follower lean his head round to watch. “Shit,” she thought, pressing on. Ahead of her, a railwayman in Polish uniform, one of many employed by the Germans, was standing by the passenger door, ready to open it at the first suburban station. Zo was direct. I am from the Home Army, she told him, her eyes bright. “Get the door, I'm going to jump.” For a moment, he thought she might be mad, but Zo had natural, impatient authority. Dropping his hand to the lock, he leant in and pushed the door wide. As though partners in a dance, in the same fluid gesture Zo swung herself round to face the rushing night air and threw herself from the moving train.’

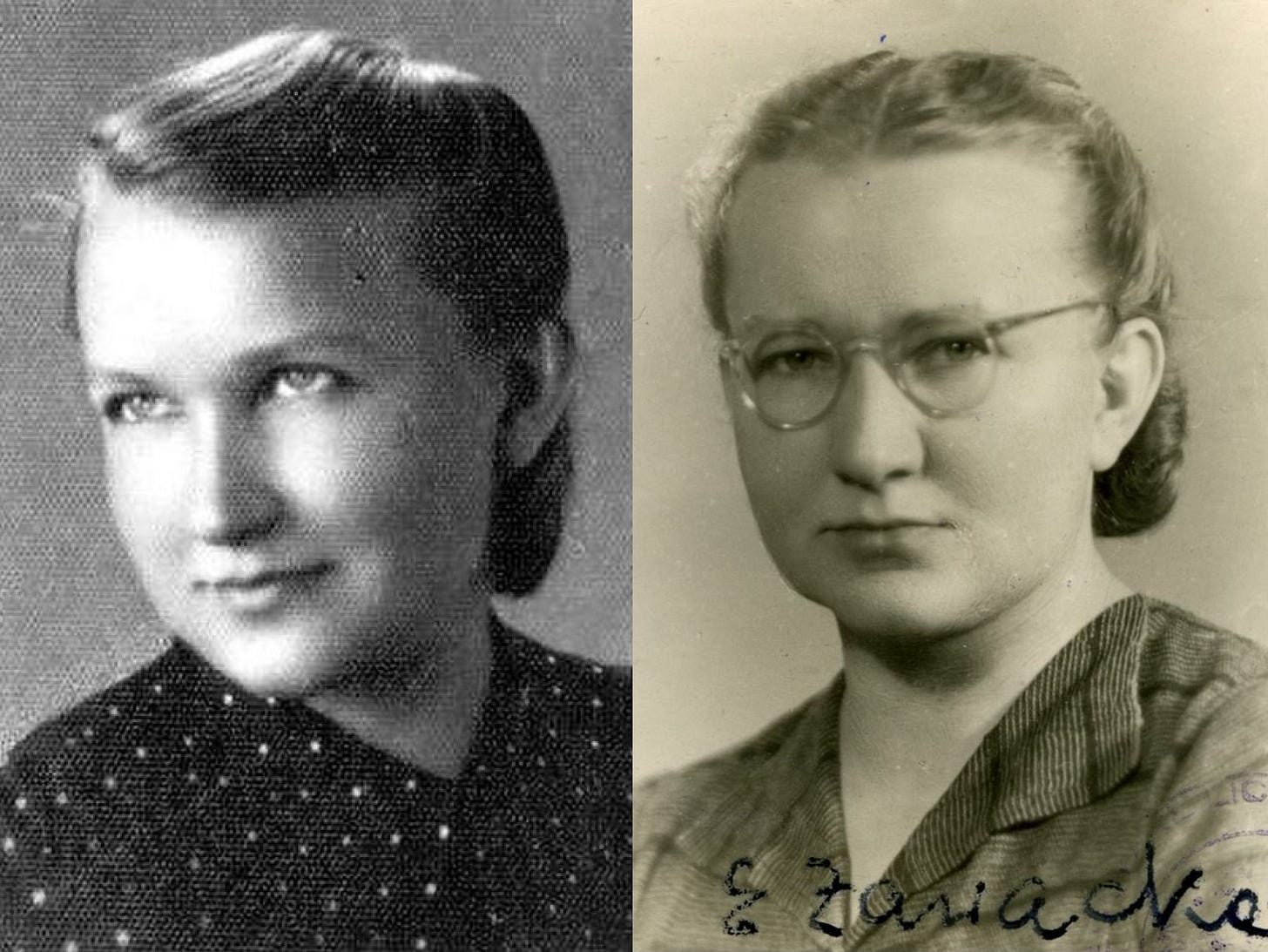

Zo was adept at constantly changing her appearance. These photos are from wartime identity records (Elżbieta Zawacka Foundation, Toruń)

To find out how she got away, you’re going to have to read the book.

Zo was burned on the Berlin to Silesia route. Soon she found that she was on the Gestapo’s most wanted list. Posters with her name on were pasted onto station walls at Kraków. The Gestapo knew her name, her date of birth and where she was from. Zo could not go home. She was stripped of her identity, as the Home Army created a new one for her. Her hair was dyed reddish brown, she relocated frequently, went about in disguise. She was somewhat safe from capture now, but she was unable and unwilling to take a back seat for the rest of the war:

‘Zo had no false modesty about her abilities, but she was astounded when her new orders arrived. It was, she admitted, “unbelievable, stunning news”. Zo, a female volunteer with no military rank, was to be the first and only woman appointed as an emissary, in her case the personal representative of General Rowecki himself, commander of the Home Army. Her improbable, perilous assignment was “to cross the whole of Europe”, several thousand kilometres, and reach the General Staff of the Polish Forces in London.’

The type of key in which Zo would have hidden microfilm to smuggle across borders (Elżbieta Zawacka Foundation, Toruń)

Suffice to say, Zo is just getting started. She wasn’t merely a courier, she was a soldier, a resistance fighter, an operative who risked her life for her country only to find that victory wasn’t really victory at all.

Agent Zo: The Untold Story of Fearless WW2 Resistance Fighter Elżbieta Zawacka, has been published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson and is available now from your favourite booksellers in the UK. It will be released in the US on 3rd December, and in Poland at the beginning of next year. You can follow Clare on Musk’s cess-pool hell site @claremulley where she considerably raises the tone.

I’m a fan of Clare’s books and my plan is to pick up a copy of Zo at WHWFV, get it signed too hopefully. I’ve been fortunate to meet Clare and chat with her over coffee, charming and patient are the words I would use.

Really looking forward to meeting the wonderful Clare at Chalke History Festival, where I'll be getting my copy of Agent Zo. I'm sure this will be as fascinating as her previous work.