Free Weekly Digest

This is your free weekly round up on what’s been happening in my history world. This week I came away from WW2 and on Monday I went for something at the other end of my comfort zone with the industrial revolution. In another piece on vanished occupations I looked at unfortunate children who helped build Britain into an economic powerhouse in the 19th Century for basically no reward. I used the memoir of one such employee who was seven when he entered a mill in Nottinghamshire…

This publication exists thanks to subscribers. For £5 a month, they fund the time and effort required to put it together, which makes them some of my favourite people. In return, they get a minimum of seven articles and a podcast for their money. If you like what you read, please consider joining them

Health and safety was non existent in the workplace. Minor injuries were sustained every day at Lowdham Mill.

Some had the skin scraped off the knuckles, clean to the bone, by the fliers; others a finger crushed, a joint or two nipped off in the cogs of the spinning-frame wheels. When [Blincoe’s] turn to suffer came, the fore-finger of his left hand was caught, and almost before he could cry out, off was the first joint… he clapped the mangled joint, streaming with blood, to the finger, and ran off to the surgeon, who, very composedly put the parts together again, and sent him back to the mill. Though the pain was so intense, he could scarcely help crying out every minute, he was not allowed to leave the frame.

Robert went into much detail in later life about the worst incident that he witnessed:

A girl, named Mary Richards, who was thought remarkably handsome when she left the workhouse, and, who might be nearly… ten years of age, attended a drawing frame, below which, and about a foot from the floor, was a horizontal shaft, by which the frames above were turned. It happened, one evening, when most of her comrades had left the mill, and just as she was taking off the weights, her apron was caught by the shaft. In an instant the poor girl was drawn by an irresistible force and dashed on the floor. She uttered the most heart-rending shrieks! Blincoe ran towards her, an agonised and helpless beholder of a scene of horror that exceeds the power of my pen to delineate. He saw her whirled round and round with the shaft—he heard the bones of her arms, legs, thighs, etc. successively snap asunder, crushed, seemingly, to atoms, as the machinery whirled her round, and drew tighter and tighter her body within the works, her blood was scattered over the frame and streamed upon the floor, her head appeared dashed to pieces—at last, her mangled body was jammed in so fast, between the shafts and the floor, that the water being low and the wheels off the gear, it stopped the main shaft. When she was extricated, every bone was found broken— her head dreadfully crushed—her clothes and mangled flesh were, apparently inextricably mixed together, and she was carried oft, as supposed, quite lifeless. "I cannot describe," said Blincoe, "my sensations at this appalling scene. I shouted out aloud for them to stop the wheels. When I saw her blood thrown about like water from a twirled mop, I fainted. But neither the spine of her back was broken, nor were her brain injured, and to the amazement of everyone, who beheld her mangled and horrible state, by the skill of the surgeon, and the excellence of her constitution, she was saved." Saved to what end? the philosopher might ask—to be sent back to the same mill, to pursue her labours upon crutches, made a cripple for life, without a shilling indemnity from the parish, or the owners of the mill.

This girl had been literally racked in front of him. Did anyone do anything about any of this?

They tried. One widow received a letter from her daughters, Fanny and Mary, from the mill. They bemoaned their health, their diet, their workload and much. Their widowed mother, who had had to surrender them to the poorhouse at St. Pancras, actually travelled to Lowdham. She spent a fortnight examining the conditions at the mill for herself, and then, without complaint she left. Instead of taking the matter up with the owners, who she probably had no faith in, she went to the parish officers of St Pancras, responsible for sending her daughters there and convinced them to send a committee to investigate. If it might have done some good, her efforts were rendered pointless when Lowdham Mill stopped trading shortly afterwards.

You can see how all this fits in with the wider history of the Industrial Revolution and what happened to the child in question:

Then on Thursday I went back to my WW1 ‘not everything is about the BEF’ schtick with a piece on the inundations at the very northern end of the Western Front in autumn 1914…

What happened here? The most clickbaity version goes a little something like this…

‘The resistance of a handful of heroes against an enemy infinitely superior in number and power; the terrible imminence of the abandonment of the last shred of Belgian territory and of a rupture of the front uncovering Calais. The exhausted defenders were weakening, facing the retreat towards France. But during a tragic night, a brilliant inspiration illuminated the brain of an old lock-keeper who, by a desperate manoeuvre, opened at high tide the gates that protect the country against the sea. The flow becomes liberating: at dawn, a liquid rampart extends in front of the Belgian front, pinning the German advance in place.’

For a start, we’re not quite sure exactly who came up with the idea of flooding the very end of the emerging Western Front to keep a last shred of Belgium out of German hands. Also, whoever it was, he wasn’t the first to think of it. Belgium and indeed the Netherlands were well versed in the concept of flooding territory to hold back an invader.

Secondly, we’re not talking a biblical flood that inundated the battlefield, washing it clean of the enemy in thirty seconds. Thys was a better killjoy than I am:

The flooding manoeuvres required the opening of the sluices and locks before high tide, to allow the water to enter the country, but also their closing before low tide, to prevent the water from flowing out; the same manoeuvres had to be repeated several times, and for several days, to obtain a sufficient water level. All this seems simple and obvious when one thinks about it afterwards, in cold blood and with the lessons of experience, but I affirm that it was really too complicated at the time of the battle, without any precise information on the topography of the places and on the levels and times of the tides, to be the work of a single man.

The legend of the Yser,” he claimed, was about more than a single individual. And it deprived a whole pile of people who bravely worked to create a giant natural barrier to halt the invading German armies. Thys commanded some of them, namely a unit of Pontoon Sappers, from the Belgian Army’s engineers. He also paid his respects to many more in his memoir. ‘Belgians or foreigners, who collaborated in this corner of the front in the work of the saving floods.’ His book was equally dedicate to the British and the French.

To find out what happened on the Yser, continue reading here:

News

I’m just back from summer tours and I wanted to hit pause and take an opportunity to tell you about all the ways you can share your love of history with events and trips I have planned.

In the UK, the Great War Group conference is coming up in October. This is the charity I co-founded in lockdown, aimed at giving people a chance to learn about the First World War in a like-minded community. Our annual conference takes place over the course of a weekend and each year we move it somewhere new in the UK in order to make it as fair as possible. This time, we’ve picked the bright lights of Leicester.

Friday evening is always a bit more light-hearted, and this time after dinner I’ll be hosting a quiz based on the University Challenge format. Trustee Andy Lock will be captaining The Sneaky Beavers, and stately (lols) historian Peter Hart will be leading The Naught Sausages into action. Given that he freely admits he doesn’t do dates, names or places this should prove entertaining for everyone else. The rest of the teams will be selected from audience volunteers the night.

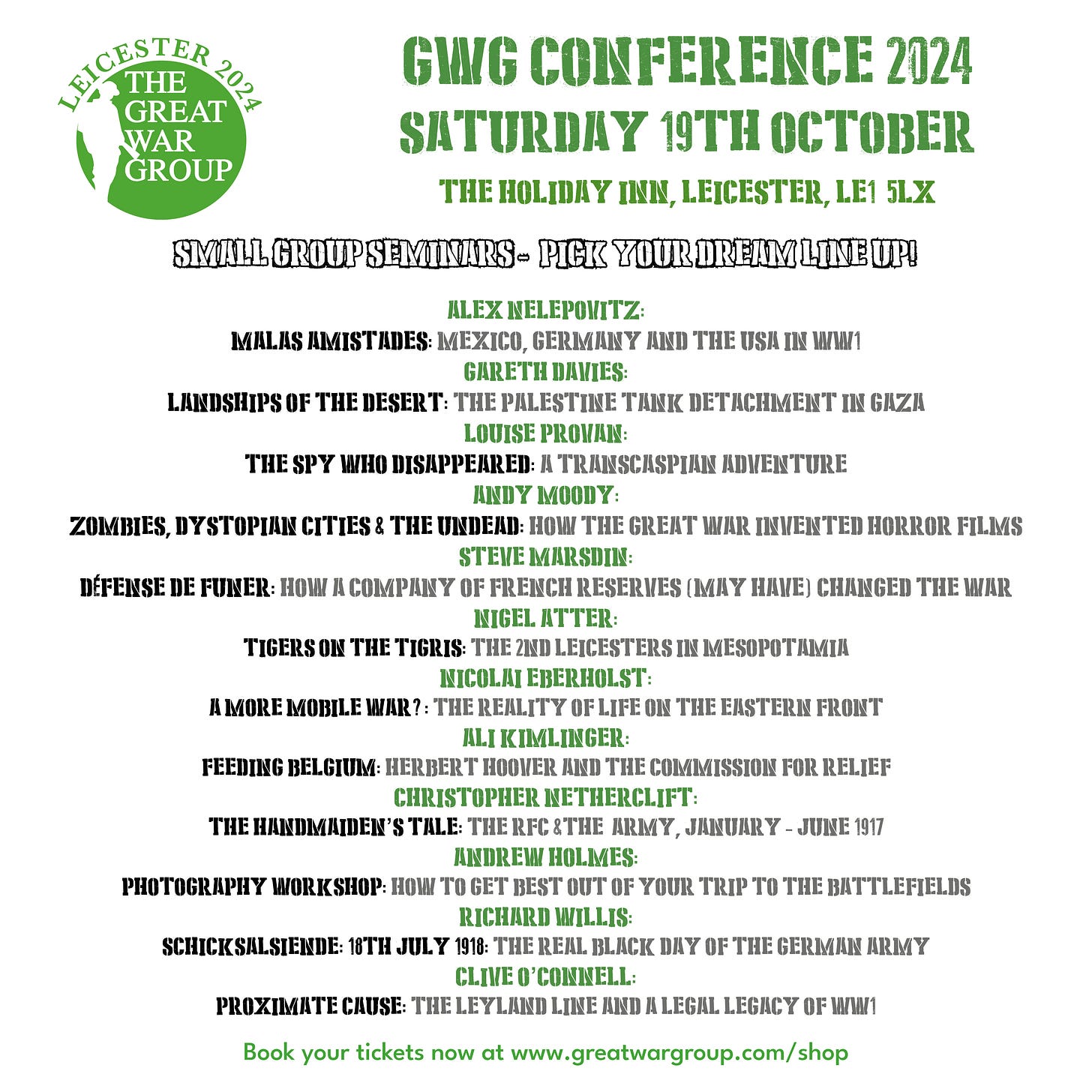

The Saturday is always packed with WW1 content from a diverse array of fronts. There are a number of small group seminars for you to pick and chose as many (or as few) as you like, and three keynotes.

This year our big talks come from Professor Sir Simon Wessely, a renowned expert in psychiatry as he examines a shot at dawn case where much evidence revealed a clear mental break in the case of the defendant. Vanda Wilcox will be flying in from Italy to talk all about Libya and the war in North Africa. And Peter Hart will be examining the early days of some of Britain’s leading WW1 generals nearly 20 years before in the Sudan. Here’s the details of the seminars:

Because it’s us, we’ve also bagged a bar on the Saturday night to wind down after a busy day. The weekend always finishes off with a remembrance service for the local war dead wherever we are. If all of this sounds like something you’d enjoy, you can book tickets or reserve one with a deposit here:

As for tours, there are a few to choose from.

This one is all very last minute, but we’re dead keen and if we’re quick, we can get it off the ground. Sword Beach author Stephen Fisher and Lowlander expert Andy Aitcheson are primed to lead an anniversary tour - it’s 80 years since operation INFATUATE. This means you’ll be getting the very best introduction to amphibious assaults: 4 Special Service Brigade, 52nd Lowland Division, the Canadians - and the background to opening the port of Antwerp in 1944.

Bookings are coming in fast for our Jordan trips next year. This is one of my very favourite places on earth, and there are two variants based on the activity level you’d like to commit to. Either way, you’ll spend a week immersed in the history of T.E. Lawrence and the Arab Revolt. This tour takes you places no other group on earth goes. We know, because the locals make fun of us for it. You’ll experience breathtaking Wadi Rum, explore up and down the Hejaz Railway, walk in the footsteps of a legend and of course, we can’t not take you to Petra. If you’re thinking about this one I can’t emphasise enough how you need to get your skates on. There is a chance that a new high speed rail link might cause the Hejaz railway’s destruction, and owing to the Thailand tour (2026, see below) we will not be offering this in 2025.

Naval Historian Kate Jamieson and I are also getting excited about leading a week long tour to Orkney next June. You can register your interest now for a packed programme of WW1 and WW2 naval history, with an obvious diversion to Skara Brae because we couldn’t possibly drive past it. We’ll also sneak in a brewery/distillery stop too.

In August 2025, I’m going to be taking a group to the Ardennes to take an in-depth look at why this area keeps getting beaten up time and time again. All will become clear when we walk the ground, but we’ll be looking at the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, and the Battle of the Frontiers in 1914. When we get to WW2, it’s all about the Maginot Line and 1940, before we cover the Battle of the Bulge.

I’m so massively excited about this one, because I’ve found an awesome way to channel my interest in WW2 in Asia and the Pacific with my love for Thailand. This tour covers multiple locations throughout this beautiful country and is a real bucket list itinerary. It comprises multiple aspects of WW2, with the last surviving stretch of the Thai-Burma railway as our centrepiece. Around that we’ll weave a day spent as up close and personal as you’d like to get with elephants, stops to take in Thai culture, and we’ve even worked up an optional beach add on for those who want to stay a little longer.

This publication exists thanks to subscribers. For £5 a month, they fund the time and effort required to put it together, which makes them some of my favourite people. In return, they get a minimum of seven articles and a podcast for their money. If you like what you read, please consider joining them

Alex I really enjoyed those pieces related to the early industrial workings that went on during h early years. It seems that all industrial nations went thru he same growing pains in the past.